You spoke with a pretty eclectic group of workers for this project. What were some of the common themes that emerged in your conversations across jobs and demographics?

You spoke with a pretty eclectic group of workers for this project. What were some of the common themes that emerged in your conversations across jobs and demographics?

Maximillian Alvarez: I’ve been interviewing workers for a number of years now — for my podcast Working People, for The Real News Network, and for this book — and one of the most difficult things about doing this work is trying to simultaneously honor the beautiful, irreducible uniqueness of every person’s life story and show how connected our struggles are, how much we have in common. As I write in the introduction to the book, “We are all, by virtue of being ourselves, unique. And that means something … There are, of course, many things and experiences that we have in common, and those things bind us together.” I think the commonalities that most jump out to me are: Every interviewee in the book is a complex, smart, deeply feeling, highly skilled person who deserves to be heard, just like you, just like me. I know that sounds basic as hell, but working people’s voices and expertise and human worth are so easily shut out and devalued in our culture; I hope that anyone who reads this book will see what a tremendous, uncoincidental injustice that is.

One theme that seems present in every worker’s testimony is that COVID-19, and the responses to it by our governments and employers and the media, clearly showed how much this economic system counts our labor as “essential” but our lives as expendable. I think every worker I spoke to articulates in their own way that they know their lives are worth more than that, that we deserve better than that — and I think this same feeling has been fueling a lot of the labor activity we’ve been seeing over the past two years, from strikes and unionization efforts to the Great Resignation.

You have an impressive academic background. How has your time in academia informed your current public-facing work?

MA: Ha! Thank you. I have an uneasy relationship with academia, to be honest. I’m first-generation Mexican-American, the first person on either side of my family to get a PhD. Generations on both sides of our family struggled through poverty and much more so that my siblings and I could get a good education. So I always felt a deep responsibility to make whatever I learned useful and usable to my friends, family, and people like us, and that’s what I try to do. But academia always seemed to be pulling me in the opposite direction, incentivizing me to become more of a priest in the temple of esoteric knowledge, to be a speaker of special languages that were inscrutable to people like my family or the coworkers I had at restaurants and warehouses.

That’s why I started doing more public-facing work while in graduate school, even though I was discouraged from doing so because it wouldn’t help me get an academic job and wasn’t seen as serious scholarly work. Don’t get me wrong, I love theory and reading giant novels and dense history books, but writing for magazines and speaking on podcasts was one of the ways I tried to take the treasures of higher education and smuggle them outside the ivory tower. I will say this, though: the thing that taught me how to do that effectively, the part of my academic “training” that has been more helpful than anything else in making me a better public scholar, public intellectual, or whatever you want to call it, is teaching.

Being in a classroom with hungry-minded undergraduates, bringing our respective experiences, thoughts, and vocabularies to the table, learning as much from each other as we learned from the dense texts we were figuring out together — that’s where I felt most intellectually alive. I try to channel that same spirit of respectful, open, collaborative knowledge making in the public-facing work I do.

The Work of Living is a history of the pandemic that by virtue of preserving the stories of those at the bottom of the economic ladder also feels like an archival project. Why are these stories important not just for us, but for future generations? What are the stakes?

The Work of Living is a history of the pandemic that by virtue of preserving the stories of those at the bottom of the economic ladder also feels like an archival project. Why are these stories important not just for us, but for future generations? What are the stakes?

MA: What’s at stake, I believe, is everything. Everything. In the US alone, we’ve lost over a million people to COVID, to say nothing of the countless others whose lives have been irrevocably damaged by COVID. I interviewed 10 workers for this book, and in those interviews you get just a tiny sense of how beautiful and vast and rich every life story is, how precious every life is, how much every one of us is connected to — and has an impact on — the people and world around us who are no longer here.

They are not just numbers on a spreadsheet; they were human beings, tee-ball coaches, coworkers, family members, neighbors, fellow parishioners … How can we possibly measure the human toll, the unfathomable loss, we’ve just experienced? How can we quantify all that’s been stolen from us? How can we forgive the failures of our governments and our economic system whose callousness, greed, and jingoistic competitiveness made this all so much worse than it could have been? By reducing our fellow human beings to numbers, by washing out all that they were and all that their lives meant, we learn to accept the unacceptable reality of mass death, and that, in turn, prepares us to accept the inevitability of more mass death, whether that death is brought by more war, more pandemics, climate chaos, or all of the above.

I can only hope that my work to lift up and honor the humanity of our fellow workers plays a small role in reminding us that it doesn’t have to be this way, that we as a species can do better, that we deserve better, and that life is precious and worth fighting for.

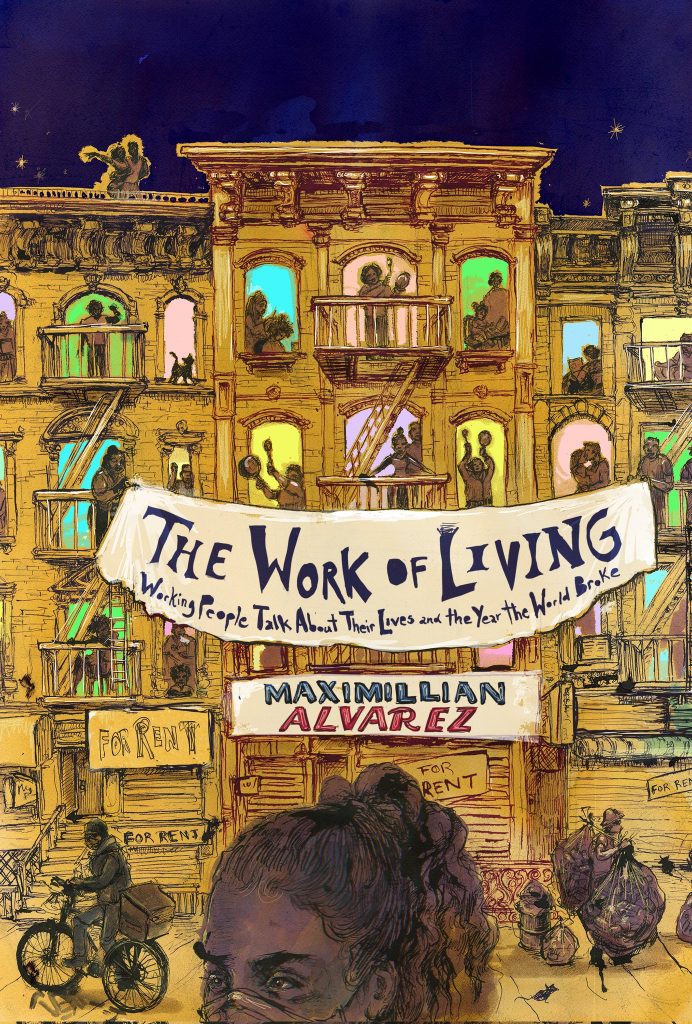

The Work of Living: Working People Talk About Their Lives and the Year the World Broke is available from OR Books.