The Moniker of Singaporean art collective Holycrap says a lot about them: for one, they are brought together by their love of rubbish. Not the likes of black trash bags and rancid sewage, but the fragments of memories — and the most mundane of moments — that they forged together. The Holycrap collective is, after all, a family affair, parents Pann and Claire Lim alongside their children Renn and Aira.

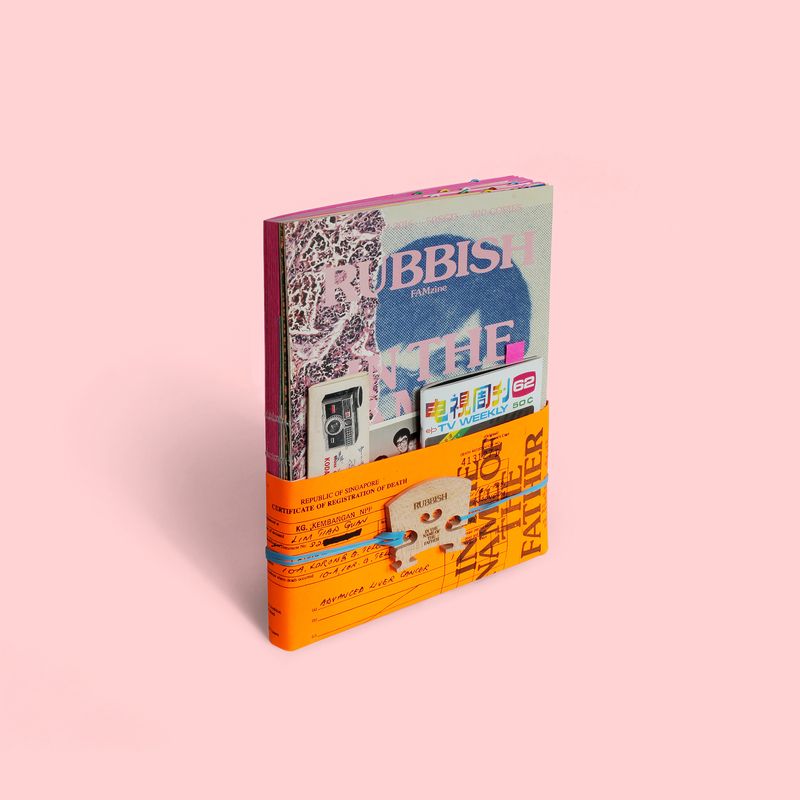

Their award-winning biannual zine, “Rubbish Famzine,” centers the countless anecdotes the family shared with one another over the years. Their inaugural issue, published in 2011, was presented as mementos stuffed within a literal garbage bag, filled with crumpled papers and a zine, based on their family trip to Tokyo and Kyoto.

“Rubbish is nonsense lah. It’s not exactly trash, it’s like trash with meaning… trash with meaning is nonsense,” Aira quips over a Microsoft Teams call.

“It’s just a term we used to joke around with or just discuss things, even when referring to good work,” adds Renn.

“When we were thinking of that word, and because it’s said so commonly, so often [within the family]… we didn’t want it to be too serious. We’re just doing a fun thing together,” explained Claire. “And if people do look at it as rubbish — rubbish as in the true meaning [of the word] — it’s fine by us, you know? We were doing this thing for us, for the kids. And so a word as such that we use often… it just means it’s something fun and nonsensical to us.”

The Rubbish Famzine is more than just a bite-sized print magazine; it’s also a painstaking labour of love, with every single issue put together by hand as a family.

Take issue three, titled “Forever and a Day.” The zine was packaged within an old-school biscuit tin — the quintessential icon of Singaporean childhood — alongside ephemera such as a paper plane, twigs, cassette tapes and brochures. The issue is conceptualized as a time capsule of the art collective’s dearest memories as a family. And with their tenth issue, “No Time for Melancholy,” in which Holycrap reminisced about a trip to Japan in the midst of the pandemic, was made to appear aged, with the corners of all 300 issues of the zine curled manually by hand. And as a finishing touch the entire zine was bound by an old Casio watch, paper clips, and rubber bands.

It was thus no surprise that uncanny Holycrap has won several local and international awards for the Rubbish Famzine over the years, including the Singapore Creative Circle Awards, The One Show from New York, the D&AD award from Britain, and the Cannes’ Design Lions.

Yet their process of creating the zine has barely changed over the decade. The first stage is a brainstorming session by the family, followed by Pann and Claire planning the production schedule. Pann typically takes charge of the zine’s design, while Claire does the bulk of the writing. Meanwhile, Renn and Aira create the zine’s illustrations, with the collective convening a few weeks later to discuss the publishing schedule and production. “[The process] has become kind of organic,” says Pann.

What has changed, however slightly, are the roles each member has adopted. When the Rubbish Famzine was conceived, Renn and Aira were eight and five years old respectively; remarkably young creatives, but still impressionable children who were largely happy to follow in the footsteps of their parents. This year, Renn and Aira will be turning 20 and 17, with Pann adding that their contributions to the zine are “smaller and more specific, as if they had become freelance writers for their parents, on top of conventional chores. They have more commitments outside of Holycrap and other hobbies as teenagers and soon-to-be adults.

“When Renn was around 14, we already roughly knew he would have less time with us for sure, so we started to treat both of them like freelancers,” Pann says. “So after we brainstorm, and we agree [on a] topic, for example, then me and Claire will plan out the schedule…”

“…which part [of the zine] they need to do…” adds Claire.

“…and we need to send the print, let’s say in November. Then by September-ish, we should see the first draft from them. Something like that. So we give them ample time for their contributions,” says Pann.

As for Renn and Aira, devoting a not-insignificant amount of time as a child on this project means having to skip out on the occasional activities with friends. “I guess when you grow up like this for a while, you think it’s normal,” says Aira. “As you grow older, you’re like, “Wait, I don’t have time to do this,” or “I can’t go to a friend’s birthday party,” or something, because I have other things to do. But it was always quite normal and I never minded it much.”

As for Renn and Aira, devoting a not-insignificant amount of time as a child on this project means having to skip out on the occasional activities with friends. “I guess when you grow up like this for a while, you think it’s normal,” says Aira. “As you grow older, you’re like, “Wait, I don’t have time to do this,” or “I can’t go to a friend’s birthday party,” or something, because I have other things to do. But it was always quite normal and I never minded it much.”

When asked how Holycrap has nurtured her love for zine-making, Aira was quick to point out that she’s still discovering her interests, such as writing and illustration, since she was very young when the Rubbish Famzine was first published. “I don’t know what I love,” says Aira. “I’m not sure how to express it properly. Some things in my earlier years, I can’t remember very well because I was quite young. “Whatever I learned or experienced, it doesn’t stick with me as much as it would if I was doing them for the first time at this age.”

Renn admitted that he was “pretty invested in it” in the first few years, but became less so as he became older. “For me, it’s not really my hobby or passion anymore. Now my passions and hobbies are more like fitness and health. But I still enjoy doodling now and then… illustrations, mainly.”

Despite the diminishing involvement of the Holycrap progeny, there still isn’t a sense that the Rubbish Famzine is nearing its end. Pann and Claire are eager to keep the zine going as long as possible. “If we have another idea for the next one we’ll just [keep doing it],” says Claire. “And we do say that we’ll try, we’ll just keep doing until one day our ideas run out or…”

Aira interjects at this point. “I think that will be till his death bed,” as she looks at Pann, much to the amusement of the rest of the family.

That’s because the Rubbish Famzine is more than just a print or artistic project for Holycrap. While it may have begun as a lighthearted family activity, it’s also the parents’ attempt to present Rubbish Famzine as something more enduring to their children: a keepsake — even an heirloom — that they might want to come back to when they are older. “When they are in their early teens, late teens and young adulthood, they’ll go out fly off the nest when the parents are still in the nest,” says Pann, “but then maybe in their late 20s and early 30s, they will try to come back more, and that’s where you know, hopefully it’s already maybe issue 28, 29, things like that.

“These [issues] hold all the memories that they might have otherwise forgotten, like things that the two kids are saying to each other. There will be a lot of stuff that they did when they were young that I’m very sure they don’t remember. And to be frank, our old issues, they are not very well versed with them as well. They don’t really have that much interest to pick up and go and read their stuff because the meaning is not there yet. But I think the day where both of us don’t exist anymore, there’s the completion of that project, that I feel, [will make Rubbish Famzine a] full circle.”

Take the children’s shared enthusiasm for food, as the family discussed their more memorable Rubbish Famzine issues. One of them is the sixth issue, “An Emojious Odyssey of the Gluttonous Omnivores,” which explores the family’s love of Singaporean cuisine. The issue, which is packed in a Chinese takeout box that’s ubiquitous in the country, is based on their numerous trips to local food courts. Renn and Aira fondly remember their food trip across Singapore (“Because we can eat!” Renn recalls with a smile). Across Holycrap’s extensive and esoteric repertoire of zines, the fact that any particular issue stood out from the rest speaks to how tight-knit the family is.

“[When it comes to] things that stand out, it’s this type of stuff, we’re out basically doing a lot of stuff. Taking a lot of photographs,” says Claire. “This is why we wanted to do a zine, a physical thing, so we can input our little DNA [into it] and do stuff together and have fun doing it.

Khee Hoon Chan is a freelance writer who lives on the internet. They can also be seen at Polygon, The Washington Post, and PC Gamer. They aren’t that well-versed in hand-to-hand combat. They also have a Substack called Changelog.