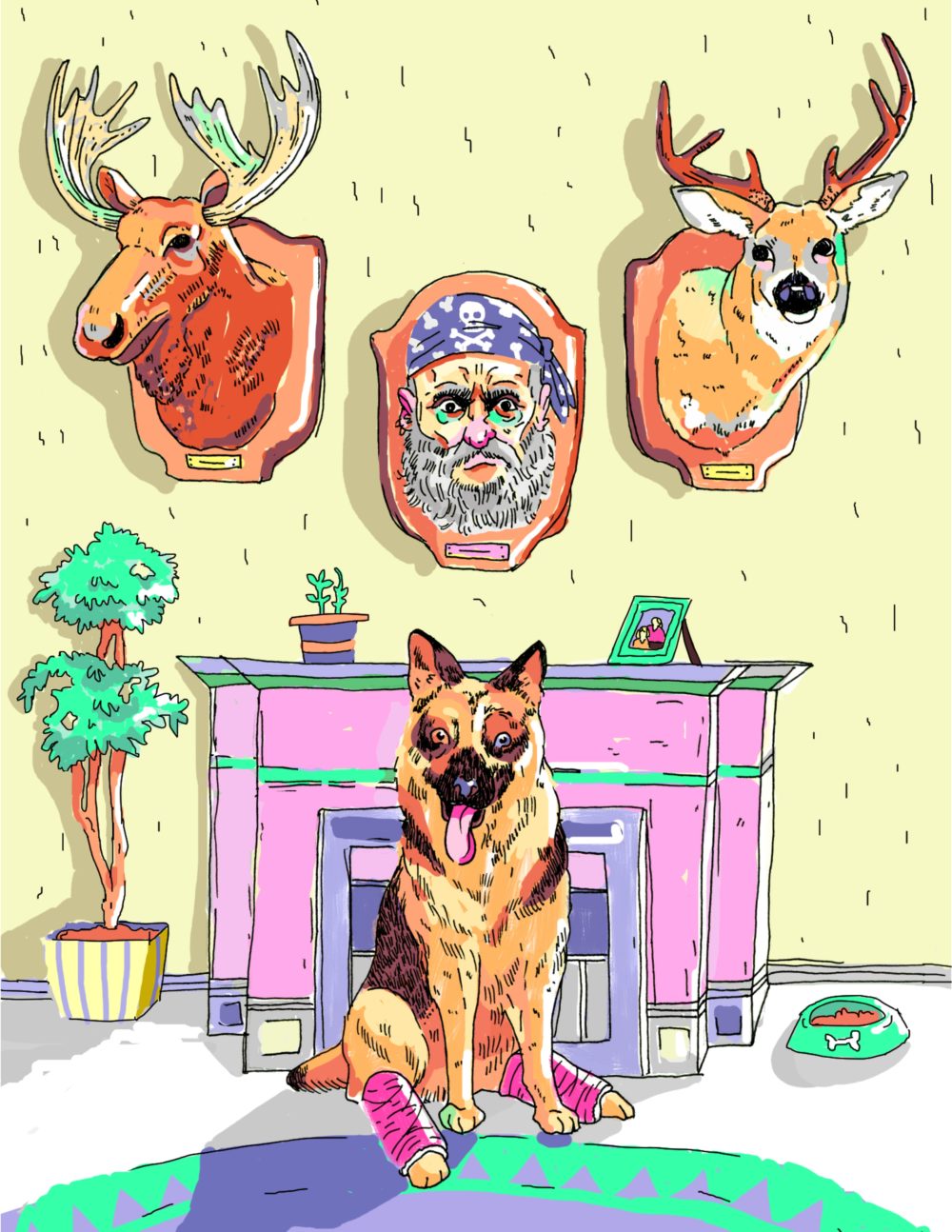

BEEN SCROLLING the internet, looking at men and dogs and so far, the dogs have it. My ex-husband found me the same way, online, on a site called A Foreign Affair. He used to joke that he’d been on the Great Ukrainian Bride Hunt and I was his prize. He really was a hunter, and we had trophy heads of deer and moose and even a bear mounted on the walls in our basement. They had glassy, predatory eyes and so I wouldn’t allow them on the main floor, in the living room. Maybe it’s because I’m a mother, and I’m trying to be more responsible than my own mother was.

Take, for example, the other day, on my way to pick up my daughter from school, zooming up Bathurst on my scooter. While stopped at a red light I saw this burly guy, middle-aged, all biker-clad, scruffy grey beard and bald head, trying to drag his dog across the street on its leash. Only the dog didn’t want to move, right? Only this dog, a German Shepherd, had two broken legs – two hind legs in casts.

The dog decided to put on the brakes, right in front of me, with its eyes – one blue and the other brown – so beleaguered. The owner looked at me and said, “Mind your own goddamn business.”

I would never sleep with this guy, I thought. Not for a million dollars (and I was going broke).

From their cars, a whole bunch of people started shouting at the guy; someone called him a monster. The lady in the BMW next to me slid down her passenger side window and said, “Someone’s got to do something.”

Was she referring to me, because I was less confined (being on my scooter) than she was in her car?

The guy pulled harder on the leash, literally scraping the dog along the pavement, and the dog howled. At first, I didn’t connect the howl to the dog; I thought it was a siren. I was afraid for that dog, I really was. And who likes seeing animals being abused? Then, and I had to look twice to believe this, the BMW lady got out of her car, walked over to the dog, scooped it up into her arms and carried it to the other side of the street. She laid it carefully on the curb, like it was a baby. She whispered something in its ear then dashed back to her car as the burly guy was approaching. That haunted me for days; I wanted to know what she’d said. I wanted to know that secret.

Sometimes, I wished I didn’t have to pick Emilie up from school anymore. I wished she could come home the way I did when I was her age.

Growing up in Kiev, I lived with my mother, who worked sporadically, and my grandmother, who worked long hours in a government office. By age seven, I wore a key around my neck on a strand of blue yarn and I knew how to use it to lock and unlock the door to our apartment. After school I would let myself in and heat up my dinner. Sometimes my mother was home. She liked to keep company with a large and noisy man who drank vodka and made her shriek with laughter. On those days, I avoided her and played with my dolls. I would have preferred a dog.

When I got to the school, Emilie was standing outside on the front steps talking to some boys I didn’t recognize. She’d been segregated into a small and specialized class and I could instantly tell that these boys were too old, too canny, for that class. Too normal.

When Emilie spotted me, she waved to the boys and headed straight in my direction.

“Who are they?” I asked.

“My friends,” she said.

“They’re too old for you.”

“They go to my school,” she said. “And they’re nice to me.”

“Emilie, if I see you talking to them one more time I’ll go right up and tell them – ”

“Tell them what? That I’m dumb? That I’m too dumb for them?”

The sun was beginning to set and Emilie marched ahead of me in a huff.

“Emilie.” I pulled her back. “Where are you going? My scooter’s right here.”

“I want to go to McDonald’s.”

Emilie was unaware and impulsive. She lived in the moment. She was also easily distracted. I could have said she’s like her no-goodnik father but that’s not true. Emilie is the way she is (the specialists tell me she has a Mild Intellectual Disability) because of me. She was born with Foetal Alcohol Syndrome. She was born drunk.

“Come on,” I said. I took my helmet and fastened it on Emilie’s head. We were the same size now, and that was good, because we only had one helmet.

Emilie wrapped her thin arms around me. “Tighter,” I said. “Put some muscle into it.”

I don’t know what I’d do if she ever fell off.

When we got home I could smell the mould growing beneath the carpet. I imagined it spreading forward in time lapse photography, overtaking our home. A rainstorm, three nights ago, had flooded the better part of our basement apartment.

I fixed supper and we ate. Afterwards, I helped Emilie with her homework. I needed to keep her busy, on task. Keep her off her phone. God knows what or who she could be looking at these days.

That night, I kept at Emilie until her eyelids began to droop then I tucked her in and kissed her forehead. I told her to hit the hay. Not to let the bed bugs bite. She laughed and told me that I always said the stupidest things. I waited to hear the steady purr of her breath before shutting the door to her bedroom. Thankfully, the scourge of mould had not spread to her safe corner.

Finally, in the privacy of my bedroom, I checked my emails. The first item was my daily list of potential matches from PlentyOfFish. I’d been on the site for only a couple of months and, so far, I’d been tossing back the scaly, slimy catch that had taken my bait. Online dating was a waste of time, I knew that, distracting me from becoming the person I was meant to be. You’d think I would have learned that meeting men on the Internet was never a good idea. Back then, with my mother whispering in my ear, “Marry a rich man,” I had no idea how bad it could get.

Why did PlentyOfFish keep sending me profiles of the same men? The same rotation of balding and ex-con-like heads? Was it because I’d never actually met one of them in person?

Lately, I was corresponding with this guy who claimed he’d created a cereal that increased your libido – Sex Cereal. He said I could find it in my local grocery store. He never suggested meeting me, nor I him, so that part of our relationship was working. I didn’t like the way he was dominating our Internet conversations, constantly elaborating on his need for anal sex. He’d sent me a picture of his erect penis and asked for a photograph of me. I thought about it, but only for a fee. I needed to seize every opportunity because it’s hard when you’ve got two mouths to feed.

A week later, dropping Emilie off at school, I noticed those boys again. They were huddled in together, heads pressed into the centre, sharing a secret. When Emilie passed by, they stopped talking and looked at her with their glassy, predatory eyes.

“Hey Em,” the tall one said. “Not so fast.”

It was a reflex, I guess, something related to the maternal instinct, my need to leap forward, to pounce, but then Emilie quietly kept going, all the way up the steps and into the school, without a word to them or me. She knew I was watching, and that’s what stopped me in my tracks. A mother’s got to do everything she can. So I stuck around a half hour longer, just to make sure she wasn’t tricking me. Just to make sure she didn’t come back out and join them when she’d thought I’d already gone.

I came home and looked at dogs for adoption on the Humane Society website. The regulars appeared — the misfits nobody wanted. I felt like those dogs — too damaged, too much work for anyone to want to take on.

But there was a new dog. It was the German Shepherd from last Monday, with the two broken hind legs in casts. I wasn’t imagining this; it was the same dog, miserable with immobility. The eyes clinched it for me, one blue and the other brown. Her name was Roxie. She was two years and two months old. Her coat was black and brown. In her picture, she was lying on the floor, her front paws daintily crossed, her mouth open, her pink tongue hanging out. Had the owner surrendered her? Had a hero intervened, turning Roxie in and saving the day?

I suddenly imagined this dog completely healed. The casts a dim memory, both for her and me. She could run, she could rise up on her hind legs and lick my face. My memory moved into the future; my future what-iffing into the past. I am still a girl, a girl in Kiev. I take Roxie to the park to catch a ball but I keep her close. We come home together. Mama is there with that man again. They stink like smoke and liquor; their lips are glossy with perogy grease. The man looks at me and smiles; he is missing a few teeth. Roxie growls and Mama throws a cup at her. It just misses her face. Roxie whines and runs the other way. Later, in my room, Roxie and I play dolls. I’m glad to have a playmate. When Grandma finally comes home from work, it is late and she asks if Mama cooked me any supper. I shake my head. Roxie opens her mouth and pants with her big, pink tongue hanging out. Grandma feeds us both perogies in bed. She sings us a song about woodnymphs and wolves. She tells me she can tell, by the way I take care of Roxie, that I will be a good mother some day; I will be someone who cares.

I looked at the dog on the screen again, to be sure, then rushed out the door, believing in second chances.

When I got to the Humane Society, there was a line-up to the front desk. The lady in front of me held a carrier but I couldn’t see what was inside. I could smell antiseptic cleaner and something else, stinky-sweet. I wondered if that smell was coming from the lady or from what was in the carrier. I wondered if turning the other way would help things smell better, but as I turned the biker-clad guy was standing right there.

“You,” I said.

“Yeah, me,” he said. “Have we met?”

I couldn’t believe that he didn’t remember me. I didn’t know what to say. “I’m here to adopt a dog,” I said.

“I brought mine in the other day,” he said. “Injured real bad, you know. Hit by a car. I couldn’t look after her no more. So I dropped her off the other day. But I’m so lonely. I miss her something terrible. I’m hoping they’ll give her back to me.”

“I saw you the other day,” I said. “Don’t you remember me?”

”Oh, yeah. I seen you. Yeah, they keep sending me your picture on PlentyOfFish.”

The lady with the carrier turned around and shushed us.

The memory of my mother came to me – the night she came home drunk with that man. Grandma and I were asleep. I woke with a fright – that man’s open mouth breathing onto mine. I wanted to scream but Grandma told him to stand up. She walked him into the living room and shot him in the head.

A small rage burst within me. I couldn’t believe this goon had the nerve to think he could reclaim her.

“I want your dog,” I said. “That dog is mine.” ∞

_____________________________________________________________________________

Cheryl Runke holds an MA in English in the Field of Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. She also teaches writing and communication at the University of Toronto, in the Engineering Communication Program and in the Health Science Writing Centre. She has published stories in Prairie Fire Magazine and the Hart House Review. She is currently at work on a novel.

Cheryl Runke holds an MA in English in the Field of Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. She also teaches writing and communication at the University of Toronto, in the Engineering Communication Program and in the Health Science Writing Centre. She has published stories in Prairie Fire Magazine and the Hart House Review. She is currently at work on a novel.