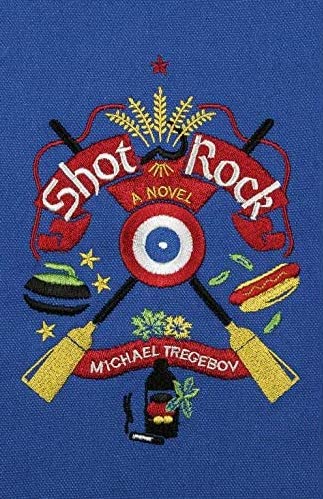

Shot Rock

Michael Tregebov, 272 pgs, New Star Books, newstarbooks.com, $22

The 1970s are trying times for Blackie Timmerman. His former wife, Deirdre, can barely stomach a conversation with him. His son, Tino, has turned into a radical socialist. And, most unnerving of all, the Queen Victoria Curling Club is at risk of closing. For Blackie, the QV is more than just a place where he plays heated curling matches alongside a crew of aging, kvetching men. It’s his refuge from a modern world that always seems to move just a little too fast.

Blackie’s nostalgia and attempts to preserve the past make his character feel out of place in the book’s modern setting. The same is true of his curling buddies, Suddy, Duddy, Chickie, and Oz. Perhaps to prove to the reader just how behind the times Blackie and his crew are, as the that describes them can be, at times, downright uncomfortable. When Duddy repeatedly “shifts his dickie” and “gingers his mole,” it’s hard to suppress a shiver. Though this awkward language is unpleasant to read, it also may be Tregebov’s way of hammering home just how uneasy Blackie and his friends are in modern times. The cost of these unsettling passages is the depiction of characters who feel wholly unrelatable (unless, perhaps, you are an old Winnipeg Jew), though, again, it is likely Tregebov did this purposefully. As the book progresses, the characters’ inaccessibility somehow works, making the reader care more about them. This paradox is evident when Blackie struggles to convey his love for his son, Tino, by engaging him in a painfully monosyllabic conversation. Such moments leave the reader frustrated, yearning for Blackie to break out of his protective, backwards-looking shell.

Even through the book’s uncomfortable moments, Shot Rock is consistently imbued with a delightful amount of Jewish cynicism — the book’s characters could be members of my own synagogue. Blackie and friends’ true colours come out not only in their profound Jewishness, but through various snippets of dialogue in which no one is really listening to each other. These tidbits paint comedic scenes, where a bunch of old men gather together, each engaged in a conversation with himself. It is in these moments that the book’s characters feel the most deserving of empathy in their quest to save the QV. In fact, Tregebov so successfully establishes the importance of the curling rink to Blackie that the reader may find themselves shocked to realize how invested in the preservation of the Queen Victoria they have become.

Shot Rock is a story about holding onto the way things have always been, and the fear of what might happen if we let go. Whether it’s a Jewish curling rink in Winnipeg or something else, this book reminds us that some things are worth fighting for.