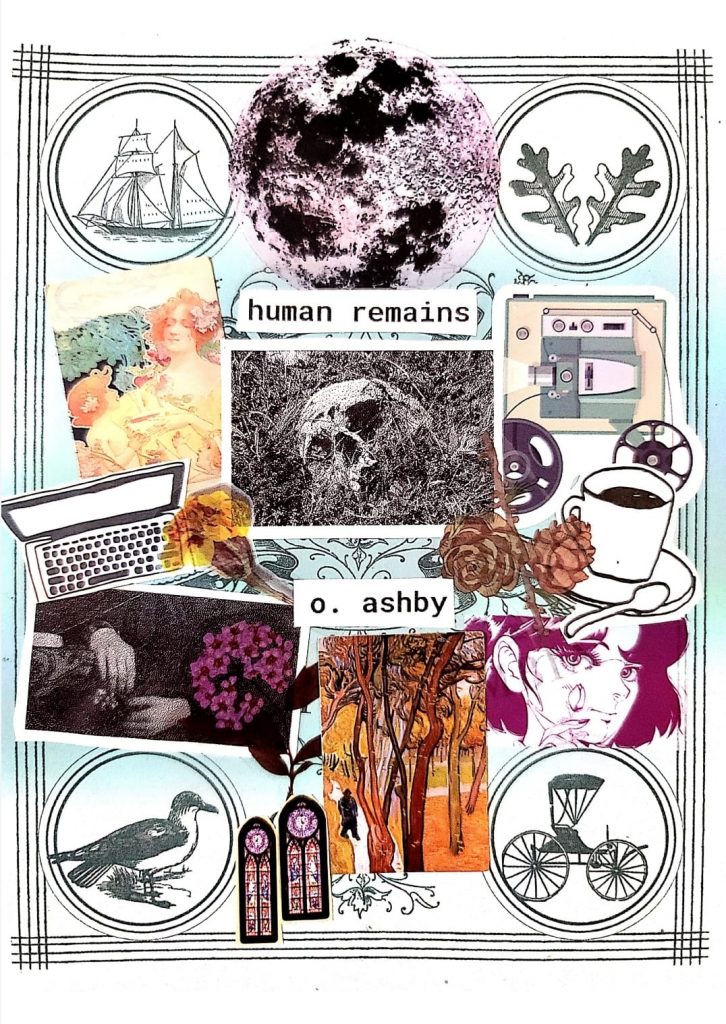

We begin, of course, with our zine of the year winner, O. Ashby. Originally from Chicago via California, she now lives with her family in Victoria, British Columbia. She is no stranger to writing, but Human Remains is the first zine she’s ever made (but not the last!). She explained to us how it came to be.

Broken Pencil: Tell me about yourself and your writing.

O. Ashby: I’m 37 and I have four kids. I live on Vancouver Island, which is a bit introverted, like me. You have to get a ferry to get here. I didn’t grow up in a home where people read and wrote for pleasure. 2010 is when I started writing for pleasure. I’d just had my first baby, and was at home nursing a lot. Later on, when I unexpectedly got pregnant with my fourth child, I had postpartum depression pretty bad. I couldn’t write no matter how much I tried, like a paralysis. So I’ve only been back to writing for three years. I finally tried poetry, which was great for two reasons. One, I felt like I could finish something, it didn’t require me to stay on it. Second, poetry forced me to have a rhythm to my writing. It forced me in a way to not become sprawling.

How did this zine happen?

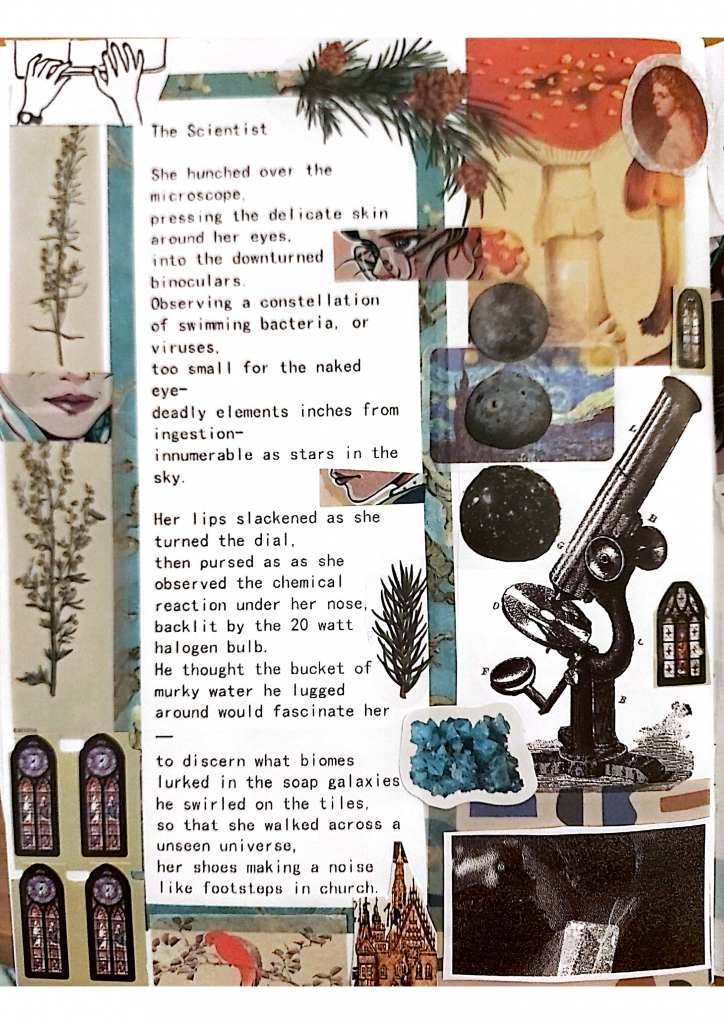

I spend a lot of time walking in the woods, and my writing percolates in the back of my mind. Home is not the place for me to tap into my creative soul. So I do this ritual where I go out and walk first and then write in the yard. I had written these poems, and my older daughter, she’s 16 and a very good artist. She posted a time lapse video of herself making this anime-themed — well, called it an art journal at the time. And I was like, “Oh, wow, that’s really cool.” She has so much stationery and washi tapes and all that. She gave me some of her stickers and said “You should try!” Soon, I started ordering way too many stickers on AliExpress! There were Victorian-themed ones, or nature or vintage-themed, just tons, and they spoke to my soul. I would search and find the right ones for the poems like I was an archeologist, or a detective — no, an alchemist.

I notice that, after 30 minutes talking, you haven’t once brought up things like publishing, the lit scene, marketing, your audience. That’s unusual these days.

When I first moved to the island, I found this coffee shop that had a spoken word night and I saw it as a way to get writing again. I quickly discovered what sort of slam poem was marketable, and so I immediately started writing for that audience. I went all in. I was performing, I even won first place for the season. But in retrospect I did not enjoy it at all. I felt like my writing needed to be marketable, but they were not looking for my Emily Dickinson energy, not at all. People wanted to hear about contemporary issues, and people wanted me to be so… I don’t know, I felt pressured as a Muslim woman who covers, too.

They wanted me to have this rebellious feminist attitude. I do have some feminist attitude, but it’s not something that I typically write poetry about. It’s not what I think about in the woods. I’m an imaginative person. The one poem that made it into the zine from the spoken word era, “Oh Eiley dear, pipes are calling,” which is a Celtic selkie-themed poem. That story of the woman who comes out of the sea and can’t go back, you could read that as a feminist statement. But I actually just love Celtic and Gaelic folklore.

How did you end up leaving that scene?

After I won the season, we competed nationally in Guelph with finalists from all over Canada. There were all these big city teams that were like, choreographed with costumes, and we were like, we are not winning this. And we didn’t. There was a lot of just angry poetry that everybody really seemed to like in Guelph, on the main stage. There’s valid anger from a lot of minorities and others, where it’s justified. But I felt like if you didn’t have an angry political poem, you weren’t well-received.

The experience made me say, “I don’t want to do this.” I could get away with the Emily Dickinson kind of poetry I write back on Vancouver Island, but not there. That’s also why I was surprised and so happy when the zine won, because I didn’t reshape it for anyone.

Did it all feel different with the zine?

I love that it isn’t about me. I don’t really desire publicity, I’m happy to just be here on my island in the woods, and nobody knows me. I don’t want people to see me and be like, “What is she all about?” I want it to be about the work. I don’t want people to have to connect to it through me first.

How much of you is in the poems, then?

In the ideas, in the settings. I get inspired by places and attach to how that place will make me think of time or mortality. The one poem, where the tree is talking about ‘darling,’ and this grave… That is actually a real place, an actual graveyard. When I was young, my grandparents had a cottage in the States. My grandmother is British, and she used to take me for these graveyard walks, which I guess is an old fashioned English tradition, like having a stroll through town. It wasn’t weird or creepy or anything. Just a tradition. Whenever I would go down to the cottage with them, we always had these graveyard scrolls.

I went back when I was older with my own kids. I was like, okay, kids, I’m going to the graveyard and they were like, Oh, God, Mom’s super weird. Going back to Culver after over 20 years, I wanted to relive that moment from my own past. And there is this gravestone that actually does say ‘darling’ that is cracked. So that’s like a real thing. As I walked up, I remember feeling, “That’s a lot of percolating going on that gravestone.”

You can purchase O. Ashby’s Human Remains and the rest of our Zine Awards winners on the Broken Pencil Zine Store!