I met David Galliquio in Quilca, the street where underground kids have hung out since the ’80s. I reckon the iconic zinester and cartoonist was testing me by showing up with a black hood obscuring his face. Was I going to feel scared or repelled by him? The intimidation tactic did not work on me. I smiled, we greeted, and he started laughing.

“I thought I was going to be kidnapped,” Galliquio joked, “I brought my revolver just in case.”

It sounds sick to crack about our daily struggles, but this kind of commentary makes us bond. In Lima, the city where I was born, that’s the norm: people seem defensive at first, but they are warm at their core.

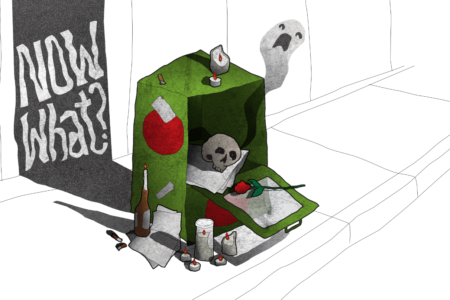

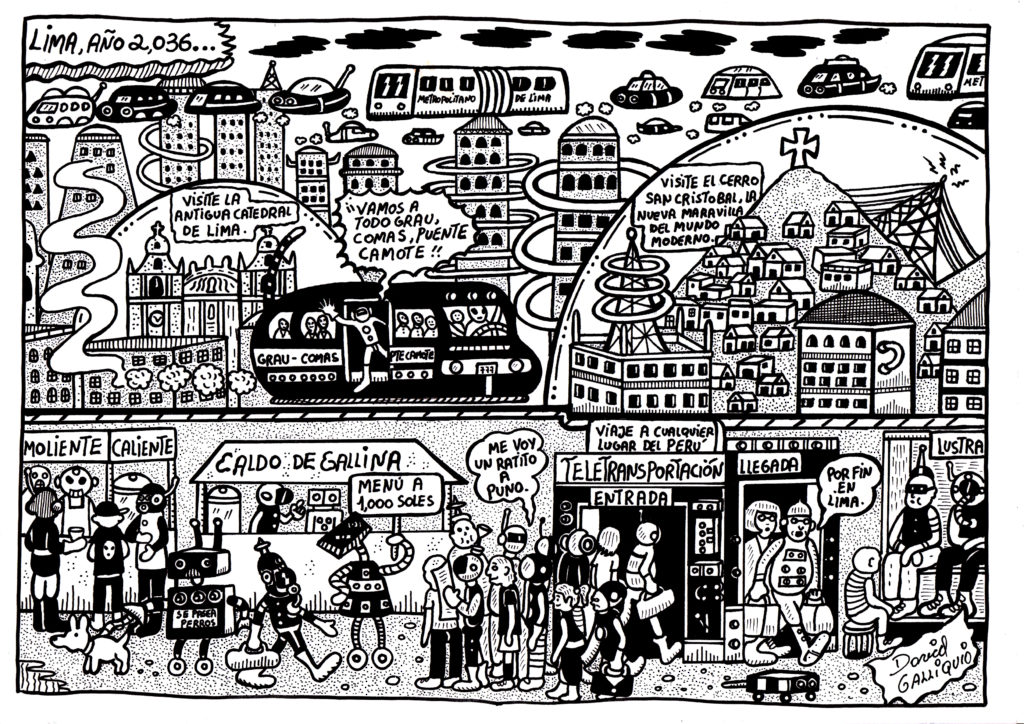

As I write this piece, Peru’s former president is being arrested because he attempted a self-coup. Pedro Castillo’s political strategy befell in four hours, and now we’ve had six presidents in five years. The conservative Popular Renewal party ordered the closure of Place of Memory, Tolerance and Social Inclusion, a human rights museum. Galleries, artists and institutions experiencing censorship is not uncommon in Peru, but many speculate the closure was in retaliation to Amnesty International, who had scheduled to deliver a report at that location. This was after more than 60 protestors were killed amongst this sadly typical chaos.

Galliquio was born and continues to live in La Victoria, an often sketchy neighbourhood. He has published six books — Lito el perro, Ilustraddicción, Barrunto, Una mozca en mi nariz, Tómalo con calma and Lágrimas de Onán. Astonishing for any Peruvian indie artist, where the minuscule publishing industry leaves almost zero chances to make a living out of artistic pursuits. He used to work at a tire factory. “I lived under a lot of stress because my job consumed all my time,” said Galliquio. “It was crazy. I worked at this factory, where tires were fabricated since the very beginning, since they were only dust.”

Galliquio was born and continues to live in La Victoria, an often sketchy neighbourhood. He has published six books — Lito el perro, Ilustraddicción, Barrunto, Una mozca en mi nariz, Tómalo con calma and Lágrimas de Onán. Astonishing for any Peruvian indie artist, where the minuscule publishing industry leaves almost zero chances to make a living out of artistic pursuits. He used to work at a tire factory. “I lived under a lot of stress because my job consumed all my time,” said Galliquio. “It was crazy. I worked at this factory, where tires were fabricated since the very beginning, since they were only dust.”

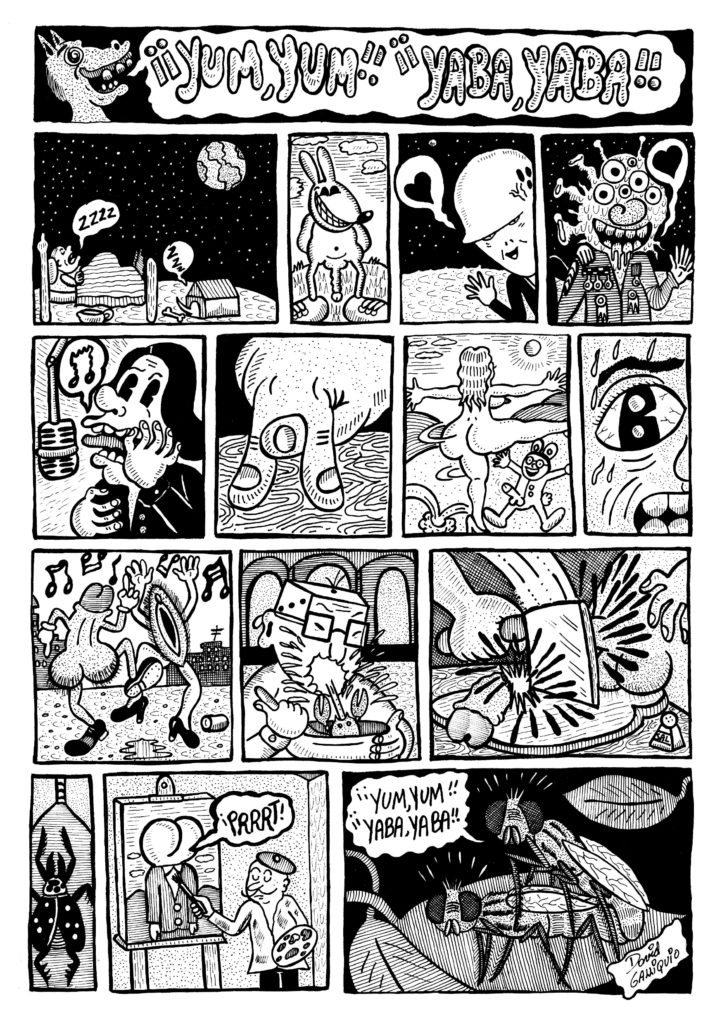

His artistic career began in the 80s, when the local scene was less than primitive, verging on nada. “I stumbled on comics in high school, fortuitously,” said Galliquio. “My father was going to beat the shit out of me because I’d burnt his radio. So I asked one of my classmates if his dad could fix it. And when I went to his place, I discovered that this dork kid was actually lightyears away from us. He already listened to Iron Maiden, Led Zeppelin and the whole Beatles discography. Turns out his father was a merchant navy, who imported comic magazines from Spain too. Legendary titles like Tío Vivo, Zap Comix and MAD magazine. I instantly fell in love with comics and I befriended this man to read his magazines. I came across Crumb that way.”

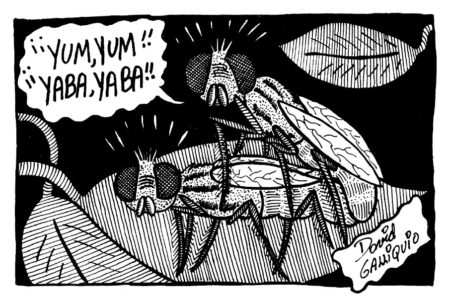

Galliquio became immersed in underground comics. Lito El Perro, his signature cartoon, an anthropomorphic, chain smoking dog he doodled 24/7, became more than a tag. “I drew Lito on all of my friends’ notebooks, so much that they were sick and tired of it,” said Galliquio. “Why do you keep drawing that nonsense? You should make something out of it, a whole chapter or something, they said.”

By the early 2000s, he began publishing in the counterculture collective zine Crash Boom Zap, where Lito El Perro gained a strong fanbase, mainly punk kids. “When we were young, we were like today’s influencers,” said Galliquio. “We went to comic events and we would have kids following us, asking, ‘Hey, are you the guy drawing those comics? Can I get a photo?’ Not having anywhere to publish, since newspapers only hired political humorists, we started making our own zines. Either you self-published or you died an N.N. (nomen nescio, an anonymous person).”

It’s not that Galliquio’s comics weren’t salient. It’s that, influenced by the 80s underground nihilist culture, the tone was too disrespectful and raw for public tastes. Lito is a bad mannered, drunk, womanizer dumbass, comparable to Crumb’s Fritz the Cat; El Negro Alacrán is an Afro-Peruvian naive man; and a lot of ink spills around nudity, stereotypes and drug use — problematic issues that he addressed openly. At 45, Galliquio will be the first to point out he was a bit dumb. “Only now do I understand those mothers who told me to fuck off while I dated their daughters,” he said. “I was always in the streets or at punk concerts. When I was 11 (his daughter’s age at the moment), I already mastered the ABC of things. That’s why now that I can look back, I’m more careful.”

It’s not that Galliquio’s comics weren’t salient. It’s that, influenced by the 80s underground nihilist culture, the tone was too disrespectful and raw for public tastes. Lito is a bad mannered, drunk, womanizer dumbass, comparable to Crumb’s Fritz the Cat; El Negro Alacrán is an Afro-Peruvian naive man; and a lot of ink spills around nudity, stereotypes and drug use — problematic issues that he addressed openly. At 45, Galliquio will be the first to point out he was a bit dumb. “Only now do I understand those mothers who told me to fuck off while I dated their daughters,” he said. “I was always in the streets or at punk concerts. When I was 11 (his daughter’s age at the moment), I already mastered the ABC of things. That’s why now that I can look back, I’m more careful.”

The birth of his daughter modified this former 80s nihilist, naturally. Galliquio used to be careless around controversy and consequences, if not court them. Now life seems different. “Seeing her with the umbilical cord changed my life,” said Galliquio. “Those who say parenting doesn’t change you are lying. It’s a slap in the face. You get another perspective, another temperament… I try to give something nice to my readers, show that grotesque things can be hopeful. That’s the beauty of building up stories, you can edit, play.”

Does he censor himself for her? No. Galliquio still believes there should be no repression in art, and such cultivation would have cursed the comics boom in Spain, Mexico and Argentina. Audiences in Lima were cold to his sex and drug cartoon ventures. “People thought I was a degenerate,” said Galliquio, “I did what I did only because the one underground rule was that there were no rules. Maybe when I’m dead my daughter will look at my drawings, she’ll say, ‘My dad did this,’ and chuckle. I don’t know. When she asks about my art, I explain it to her. When it’s too raw, though, I make something up instead, but she doesn’t believe me. She can tell I’m lying.”

In spite of new generations being more socially conscious than predecessors from the ’80s and ’90s, regarding the tenor of rebelliousness against the status quo, we do learn from our forerunners. “When I create a comic, I always think ‘This is who I am.’ If someone likes what I do, cool, and if someone doesn’t like it, that person has the right to say my work sucks. Not everyone will love you… You can sense someone is wishing you’d go fuck yourself, and that’s amusing.”

Lately, you don’t find Galliquio’s works at zine festivals in Lima, where illustrations and stickers are abound but comics, particularly long-form, are scarce. And although those in their 30s and 40s hold his work in high regard, his influence is not recognized by big cultural institutions, which tend to be bougie.

What will happen with underground comics in Lima? Galliquio now posts on the restrictively sanitized Instagram ‘because that’s the only platform.’

“Only god knows, when you’ll die,” said Galliquio, “that’s where comics will be.

Daphne Guima used to run a small online bookshop in Lima, Peru until last year. Now based in Toronto, she is about to finish a PG publishing program while doing her internship at an indie bookstore and publishing house. You can learn more about her at lasiamesadesiam.cargo.site.