Living under a Prime Minister who puts “ordinary people” and “artists” in different categories, Canadian artists never expected support from this government. But they also didn’t expect direct political suppression.

By Ashley Gaul

Franke James never thought she was on the government’s radar. Sure, she’s depicted Prime Minister Stephen Harper as a yellow-eyed devil, (“Fat Cat Canada’s Giant Litter Box,” 2009), frothing tar at the mouth, bobbing down the Athabasca River in an oil drum (“Hey Prime Minister” 2012) and hot-tubbing shirtless in an interactive “Whack the PM” game (Whackthepm.ca, 2008); still, as an independent artist, she’s never relied on funding from the federal government, and Canada is one of those countries that allows that sort of truth-to-power cheek, right?

Franke James never thought she was on the government’s radar. Sure, she’s depicted Prime Minister Stephen Harper as a yellow-eyed devil, (“Fat Cat Canada’s Giant Litter Box,” 2009), frothing tar at the mouth, bobbing down the Athabasca River in an oil drum (“Hey Prime Minister” 2012) and hot-tubbing shirtless in an interactive “Whack the PM” game (Whackthepm.ca, 2008); still, as an independent artist, she’s never relied on funding from the federal government, and Canada is one of those countries that allows that sort of truth-to-power cheek, right?

Not always. In May 2011, James was preparing her artwork for a 20-city European tour, a series of illustrations and visual essays intended to inspire youth to take action against climate change by creating their own artwork and reducing their carbon footprint. But then she received a call from Nektarina, the Croatian non-profit that had agreed to tour the show, and which “basically told me I was a persona non grata with the Canadian government,” James says. Nektarina director Sandra Antonovic told her she had applied to the Canadian embassy for a $5,000 grant to cover some of the shipping and marketing cost for the tour of James’ work. According to Antonovic, the funding had originally been approved, but was later revoked, with a question, “Who’s the idiot who approved an art show by that woman, Franke James,” and a warning, delivered by the Canadian embassy cultural officer in Croatia: “This artist speaks against the Canadian government.” Their proof? An illustrated letter to Stephen Harper (called “Dear Prime Minister”) that James had posted on her website, urging him to consider more green energy options. Said Antonovic: “Ottawa is very unhappy with your visual letter to the Prime Minister.”

Two months later, the show’s private donor withdrew its offer of support, forcing Antonovic and James to pull the plug. The show was cancelled.

James investigated. She went public. She bought an ad campaign in downtown Ottawa to publicize her blacklisting. She made art describing her experience with censorship and recently published a book, Banned on the Hill: A True Story about Dirty Oil and Government Censorship, about her experience.

A multidisciplinary artist, she became the artistic and literary communities’ de facto spokesperson in an ongoing war that Harper started when he proclaimed “ordinary people” can’t sympathize with gala-going artists in his now–infamous 2008 electoral campaign speech. There have been intimations of artistic censorship, more overtly in a 2008 proposed bill that would have granted the Heritage Minister power to withdraw tax incentives from “objectionable” films, and less overtly in $45 million in arts cuts the same year. They’ve inspired a whole genre of Harper-themed art, from Harper as Hitler, Harper as Satan, Harper as Chairman Mao, Harper nude and opulent, Harper likened to Mussolini, anti-Harper jazz songs, comic books, poetry and more. But with James, the Harper government dealt a direct censorial blow to a small, independent artist on the basis of her political opinion alone. And the difference is, it probably never expected her blowback to hit so hard.

***

It’s late February — Thursday night of the 29th annual Freedom to Read Week — and Toronto playwright Catherine Frid takes the stage at Toronto’s Garrison Pub, to a standing-room-only crowd of publishers, writers and drifters-in from the street. Franke James is there, a few rows back from the front, holding hands with husband Bill. James isn’t speaking at any of this year’s events; nevertheless, her story has come up in conversation almost daily and been written about in detail in the annual magazine, Freedom to Read. In many ways, Frid, the woman on stage, is a precursor to James. In 2010, Frid’s controversial play, Homegrown, became a rallying point for an artistic community fed up with Conservative cuts to the arts and social programs.

Sometimes serious, sometimes bewildered, sometimes chuckling, Frid’s Freedom to Read talk tells the story of how the Prime Minister’s Office condemned her play, about a Toronto 18 terrorist, before it saw its intended stage at SummerWorks 2010. “There were 42 plays at the festival that year,” she says, “and we were all really working to get advanced publicity for our shows.” So when her lead actor, Lwam Ghebrehariat, appeared on the front page of the Toronto Sun under the all-caps heading, “Sympathy for the devil,” Frid was worried. “But,” she laughs ironically, “there’s no such thing as bad publicity, right?”

The Sun followed up on its first article by publishing the names and phone numbers of the corporate sponsors who supported SummerWorks. It urged them, as well as city councillors, to pull funding for the event. None did. At the beginning of August, Prime Ministerial spokesman Andrew MacDougall said he was “extremely disappointed that public money [was] being used to fund plays that glorify terrorism.” And all this before SummerWorks had even begun.

A year later, in spite of the fact that SummerWorks had grown steadily for five straight years, the federal government inexplicably cut the nearly $50,000 slated for the event, just a month before its opening. The festival went on and the Heritage Minister denied any link between the defunding and the Homegrown controversy of the previous year, but as one theatre company director said, “It [felt] like Conservative censorship through denial of funding.” In protest, theatre directors across the country staged live readings of Frid’s play.

One outspoken Frid supporter was Toronto playwright and then-writer-in-residence at the Tarragon Theatre, Michael Healey. In a blog post for The Globe and Mail, Healey bode ill for Harper as result of the controversy: “Artists are telegenic, well spoken, organized and have access to media,” he wrote. “Inflaming them should be avoided. There’s no upside to pissing us off.”

The original Sun article became the core for a snowball that made its last impact as recently as last fall. Ironically, a little over a year after Frid’s experience, Healey would resign from his post at the Tarragon after artistic director Richard Rose refused to stage his last installment of a political trilogy, which depicted Harper right after the 2011 Conservative majority victory. Healey found other venues to stage his play and says the theatre board canned it out of fear, but Rose refused to comment.

***

Healey has no way of knowing what went on behind the scenes of his own play’s cancellation; theatres, being private, are not subject to information legislation. But immediately after her own silencing, James filed an access-to-information request and received 581 pages of internal emails and documents discussing her show from January to June 2011. Encouraged, she filed more requests. She requested all the communications concerning those initial requests, to see the reaction her digging incited. She got back more than 2,000 pages.

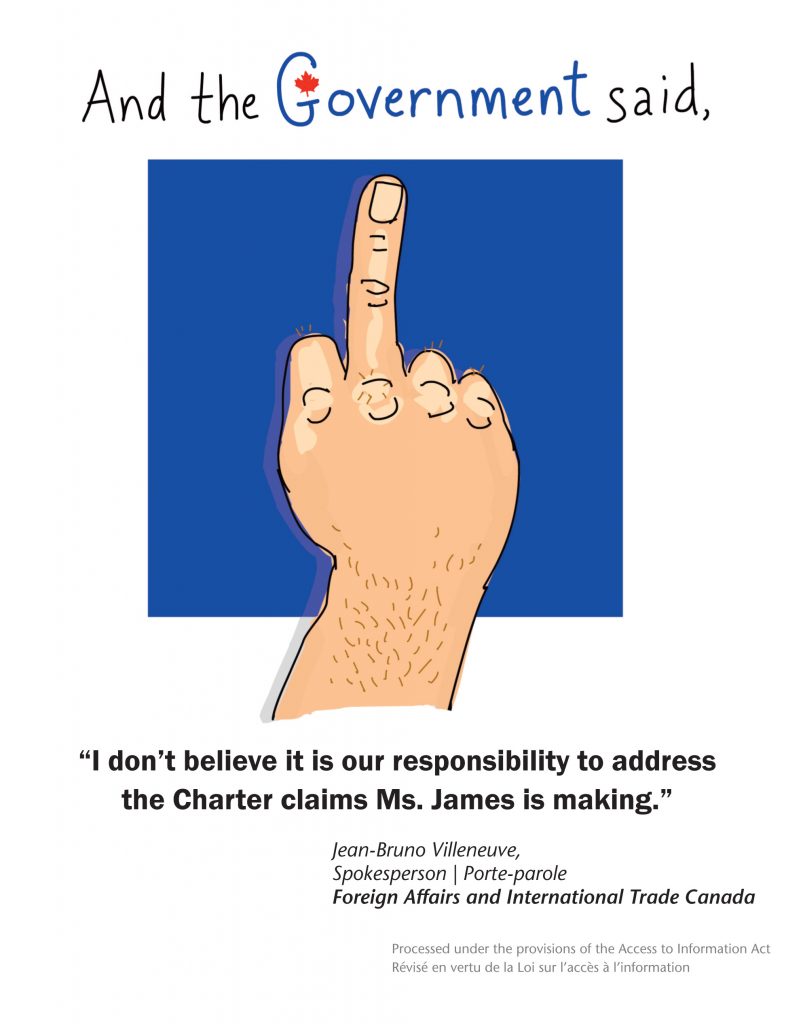

Here’s what she learned: When Thomas Marr, trade commissioner at the Canadian embassy in Berlin (one of the stops for James’ artwork on its European tour) heard about the original $5,000 in funding for James’ art show, he wrote an email to the Croatian cultural officer with the subject line, “Franke James is Your Fault.” Scott Heatherington, Canadian Ambassador in the Baltic States, wrote his colleagues to say he would not support the show, citing James’ essay, “Fat Cat Canada” in support of his refusal. More than two dozen senior officials and diplomats monitored James in the few months before her show’s cancellation, right up to Cabinet level. While telling newspaper journalists that the government had never granted nor revoked funding for James’ show, the emails and Sandra Antonovic’s experience reveal that the Canadian government was actively working behind the scenes to kill support for her work. “Why is it that what most people would call lying,” James asked in a visual essay that followed, “the government would call message control?”

Here’s what she learned: When Thomas Marr, trade commissioner at the Canadian embassy in Berlin (one of the stops for James’ artwork on its European tour) heard about the original $5,000 in funding for James’ art show, he wrote an email to the Croatian cultural officer with the subject line, “Franke James is Your Fault.” Scott Heatherington, Canadian Ambassador in the Baltic States, wrote his colleagues to say he would not support the show, citing James’ essay, “Fat Cat Canada” in support of his refusal. More than two dozen senior officials and diplomats monitored James in the few months before her show’s cancellation, right up to Cabinet level. While telling newspaper journalists that the government had never granted nor revoked funding for James’ show, the emails and Sandra Antonovic’s experience reveal that the Canadian government was actively working behind the scenes to kill support for her work. “Why is it that what most people would call lying,” James asked in a visual essay that followed, “the government would call message control?”

Perhaps in a move of deliberate transparency to counter Harper’s opaque campaign against her, James opened her investigation to the public. She ran a Twitter campaign, which spurred a reader to start a petition to raise money for it. With the help of a California-based crowd-funding service, Loudsauce, and 82 private donors, she raised enough money to buy six street ad posters in downtown Ottawa. She filled them with panels from the original offending piece, “Dear Prime Minister.” National and regional newspapers wrote about James’ struggle, and one Postmedia news reporter actually filed a similar series of access-to-information requests alongside James. They received their documents — and published their findings — at the same time: November 2011.

Shortly before that, James held a “blacklisting party” in September and invited more than 100 representatives from the arts community, environmental groups, social justice, law, politics and media. One attendee who signed the guest book pointed out an obvious irony, “that the reaction (perhaps ‘overreaction’) on the part of the government of Canada to actually ‘blacklist’ you and your work was indeed misdirected and a ‘silly’ reaction/decision as it really provided you with a new and more public platform from which to deliver your message.”

This past May, she published Banned on the Hill, a collection of eight visual essays that deal with her censorship, one of which provides tips on how to make your own access-to-information requests. As for how to best fight censorship, James’ philosophy is clear: “Get it out in the open, where everyone can see you,” she says. “There’s a great saying that sunshine is the best disinfectant. I agree 100 percent.”

So would Charles Foran, president of PEN Canada, an organization that monitors freedom of expression. “Partly through her own efforts and in part through other people,” he says, “[James’] case has gotten a lot of attention. I’d have to say, from the government’s point of view, they would have been better off letting her do the art show than to get all this bad press.”

This year, Freedom to Read Week (partly organized by PEN Canada) was more necessary than ever — from 2012, Canada dropped 10 places to number 20 in the World Press Freedom Index. Since Harper won his majority government in 2011, the muzzling of scientists has become the subject of petitions in nonpartisan journals such as Nature, and that of civil servants last summer prompted a government-kiboshed “Stephen Harper Hates Me” button campaign within the public service. But with the introduction of Bill C-30, which would require internet service providers to disclose information on Canadians’ web activity, Foran and PEN Canada decided to go further. They created Non-Speak Week, a series of radio discussions and live events on the topic of censorship in Canada. On the event website, Foran writes, “starting about a year ago, we began to note a local chill settling over that most fundamental of freedoms [speech]… ‘Non-Speak, Non-Transparency, Non-Accountability,’ was how one PEN board member described the current climate.”

Over the phone, Foran elaborates. “We did some soul-searching. We thought about earlier governments: the Liberal government, the Chretien government, Paul Martin’s government. And we came to the conclusion that the climate has changed. The Harper government does display an excessive predilection for control, insisting that organizations receiving funding be accountable not to their own mandates or causes, but first to what the government thinks they should be doing.” There have been censorious governments in the past — wartime regimes, obviously, Cold War PM Diefenbaker and Pierre Trudeau after the October Crisis all allowed for temporary censorship — but Harper’s level of message control is likely unprecedented in Canada. And the instinct goes back at least as far as 1992. Author Susan Crean remembers meeting Harper at a Writers’ Union of Canada meeting in Ottawa that year. When he learned she had written a book on the American cultural influence in Canada, Harper said tersely, “You should not have been allowed to write that book.” Crean never forgot it. “And since he gained a majority,” says Foran, “all gloves are off.”

More troubling than the immediate effects of censorship, he adds, is that “the legacy of a government that serves for any length of time in a strong-armed way is that they can shift the normal.” As an example, he cites that the number of security cameras in the parliament buildings has recently quadrupled. “And no one can explain why,” he says. “And no one has protested. Freedoms go missing when they are very lazily and thoughtlessly put at risk.”

Mixed media artist Gabrielle de Montmollin, who held a solo exhibition “Stephen Harper Hates Me” at Toronto’s The Red Head Gallery in April and May, can attest to Foran’s sentiment. Montmollin’s 28-piece show featured Harper in a Mexican wrestler mask, Harper giving the Heil Hitler salute, Harper as a clown, an ignorer of G-20 protesters and as the subject of “Ignorant Man Despising What He Doesn’t Know Standing in My Studio.” “And over and over again,” says Montmollin, “people came up to me, saying I was very brave. I don’t feel that way at all, and I was astonished at these comments. I got the feeling people thought the wiser thing would be to stay away from [Harper].”

Montmollin, like James, believes the best answer to censorship is not silence but more volume. “I just turned 60,” she says. “When I was young, artists were in opposition to society, or at least to the establishment. But that’s not necessarily so anymore. In fact, I think artists have become part of the establishment. They want to be middle class.”

***

The first thing you see when you enter the foyer of Franke James’ cozy, uptown-Toronto house, is a drawing of a faceless public servant with a Harper coif, surrounded by the words, “Who’s the Idiot…” — a reference to the email that spurred James’ two-year struggle to learn the truth about her exhibition. Drinking tea at the dining table while her husband prepares soup and almond-butter sandwiches, James says, while she’s still creating art to raise awareness about climate change and the oil sands, she’s very much added a focus on censorship in Canada and abroad to her political art practice.

It’s hard to say whether the campaign to gag her worked, but probably not. One of the only comparable Western eras where such a pronounced shift has happened in such a short time in freedom of speech is the Margaret Thatcher era in the UK. Described by investigative journalists at the time as “utterly disdainful of press freedom and open government,” Thatcher instituted a Protection of Official Information Act,” which made it possible to prosecute journalists for publishing certain information, even after it had been made public. Still, as oppressive as Thatcher was, she and Harper present a similar paradox to artists. As musician Billy Bragg, one of Thatcher’s most outspoken opponents, put it in 2009, “Whenever I’m asked to name my greatest inspiration, I always answer ‘Margaret Thatcher.’ Truth is, before she came into my life, I was just your run-of-the-mill singer-songwriter.

Sure, James’ focus has shifted and her work never toured Europe. On the other hand, it didn’t need to: James amassed a whole public of new international followers and drew attention to Harper’s growing blacklist of scientists and public servants. James clearly has more than enough energy and drive to tackle more than one topic: she recently started using a treadmill desk. And with the money she raised through her massively popular Banned on the Hill campaign, she can afford to be an independent artist a little while longer.