Immigrant kids will know this one well.

You’re at school and it’s finally time for lunch. Brown paper bags crinkle, lunchboxes are unzipped, and then someone catches a glimpse or a whiff of your food. Suddenly, your friends are losing it because the textures and smells coming from your lunch are nothing like theirs. It’s “smelly,” or “weird,” or “gross.” And this food, a gift from your family, a source of comfort at home, becomes a source of alienation and shame.

You might go home and beg your parents for Lunchables or Alphagetti, or keep this to yourself, not wanting to be hurtful or disturb the peace. Either way, a seed of shame is sown. It’s not just your food that’s smelly and gross, you are. And your family. And everyone who looks like you and eats like you.

This pressure to choose between a family’s cuisine and a plate of assimilation is a recurring trope in diaspora storytelling. In the TV series Fresh Off the Boat, Eddie Huang doesn’t want to bring his mother’s delicious xiaolongbao to school, telling his parents: “I need white people lunch. That gets me a seat at the table.”

Then, the young Eddie Huangs of North America grow up and witness a Twilight Zone shift. Suddenly, the people who once scrunched up their noses at other’s food, are now lining up outside trendy “ethnic” restaurants that essentialize staples. Restaurateurs who look nothing like the food they’re serving are getting praise for their “innovative” dishes. Meanwhile, the authentic restaurants your family has frequented for decades, where everyone is your aunty or uncle, continue to be deemed “unclean” or given racially-coded misnomers like “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

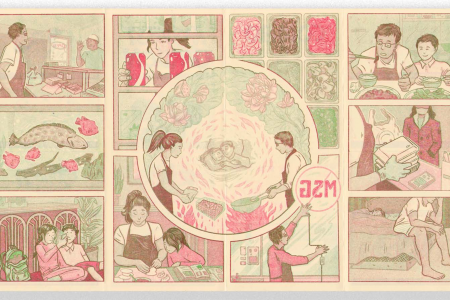

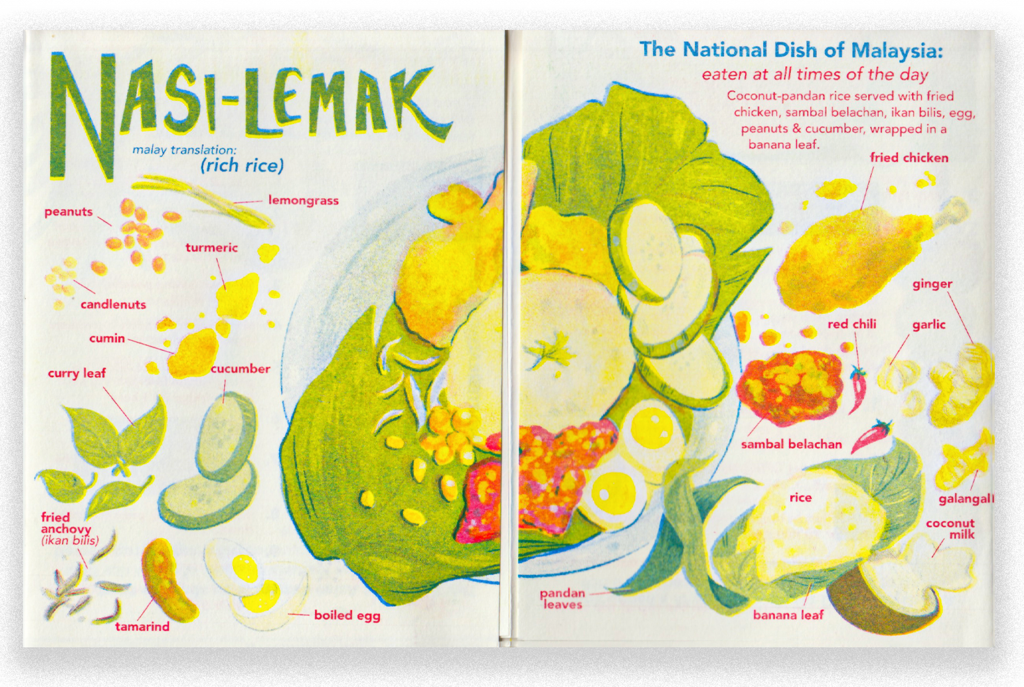

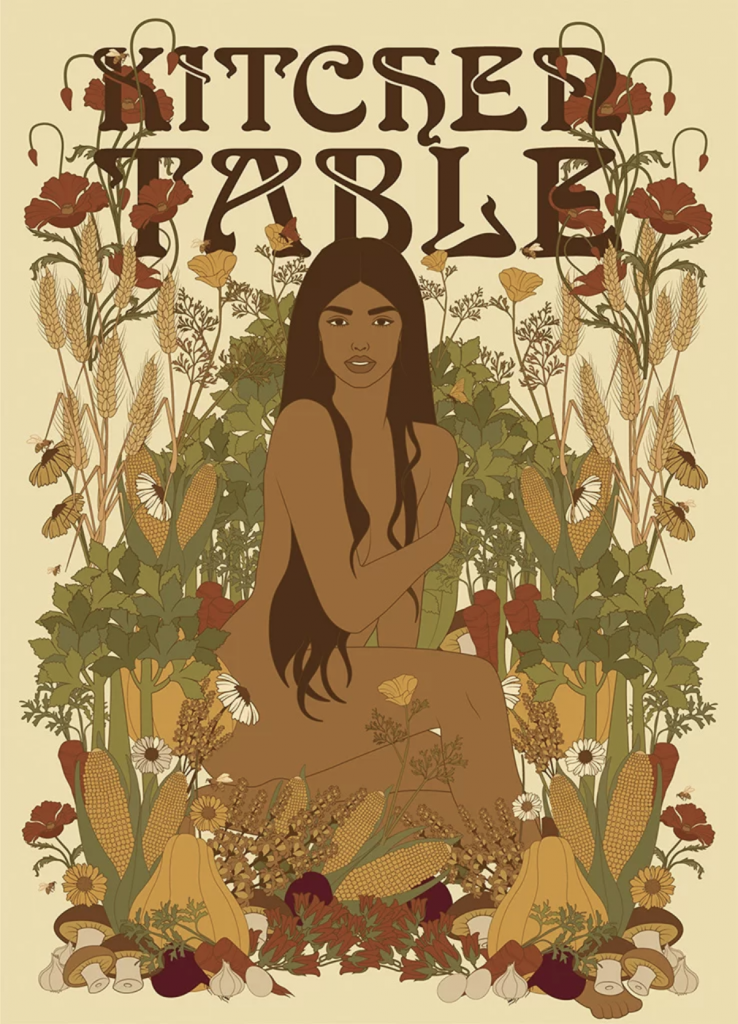

“Claiming foods with hundreds of years of history as a new trend, dismisses the food’s cultural context and implies a level of ownership,” says Meegan Lim, a first-generation Chinese-Malaysian settler with a talent for food illustrations. And mainstream food media? They’re the “repeat offenders,” she says, “perpetuating colonial, Eurocentric perspectives on other cuisines.”

The consequences are catching up to these culture bandits, as outlets like Bon Appétit face major reckonings for using “ethnic foods as a bandaid to the large systemic problems present in their organizations,” says Lim, including having employees of colour on camera, but not paying them like their white counterparts.

Diasporic children have long watched as cultural traditions get disparaged, appropriated, and exploited for profit. Now that they’ve grown up, they’re fed up. That’s why independent creators and presses are taking matters into their own hands — and kitchens — and serving up visions of better food futures on their own terms.

ANTI-FOODPORN & ACCESS

Dave Adamshick’s dealer gave him clear instructions. “Meet me in Wilshire Park, north end, by the tree.” He’d never done this before, but Adamshick was desperate. So he made his way to the Portland park, cash in hand, and did what he had to. What was he getting? A gun? Cuban cigars? An endangered animal’s pelt? No, it was something far more elusive: Baker’s yeast.

“I wish it wasn’t true,” he said. But alas, it was the height of the pandemic, and quarantiners across the land were elbow-deep in sourdough starter (my mom included) causing a major baker’s yeast shortage. What was a food lover to do but have a rendezvous in the park as if he was buying bootleg DVDs in ‘03?

The man just wanted to make some bread.

“There’s nothing more disruptive to the American mindset than not being able to buy something when you want it,” says Adamshick, contributing editor to food magazine Kitchen Table.

Many of us don’t think twice about where our food comes from. From the advent of 1950s convenience cuisine to the takeout delivery app empires of today, we’re increasingly alienated from our food. Then, as COVID-19 broke down global supply chains, we were reminded that food doesn’t just magically appear, and that many hands must labour before it arrives in our kitchens.

Reconnecting people with their food and inviting them back into their kitchens is a key part of Portland-based Kitchen Table’s ethos, says publisher Brett Warnock.

It isn’t your typical food magazine. Celebrity chefs and obscure 20-ingredient recipes are forgone for spotlights on local innovators and budget-friendly meals; fine dining reviews are replaced with profiles of diners, coffee shops, grocery stores, and farms. Packaging it all together are lush illustrations by independent creators, a far cry from professionally-plated and hairsprayed food.

“The big magazines make it look hard and impossible,” says Adamshick, who worked at the Portland Farmer Market for a decade, adding that “food porn” is an apt shorthand for the kind of glamorized, unrealistic food aesthetics we are meant to drool over but never truly replicate — especially for the many people who are food insecure even in rich countries like Canada and the US (a shocking one in seven Americans use food stamps.)

In one issue of Kitchen Table, the editors combed through grocery stores and put together recipes on a $7 budget. In another, Black Kreyol farmer and food activist Leah Penniman challenges readers to consider how food security should not be contingent on privilege, race, and wealth, and offers “practical seeds of hope toward a racially just food system.”

The way mainstream media outlets like the Food Network and Bon Appétit talk about food, you wouldn’t know that healthy food is unaffordable for many, and our food systems generate about 35% of global human-made greenhouse gas emissions. You also wouldn’t know that there are alternatives, because the food reformers rethinking these systems are barely ever given a platform in the mainstream media. Kitchen Table is one place you can find them, such as Indigenous farmer Upingakraq Spring Alaska Schreiner, who writes about how seed exchanges and banks are supporting tribal farmers in feeding their communities; or Lane Selman, founder of the Culinary Breeding Network, which helps plant-breeders, farmers, chefs, and others develop plants that can thrive in increasingly tough environmental conditions.

It’s an invitation to take small steps, to rethink our relationship with food. We’re not all plant breeders or food reformers, but we can all learn from them.

WHOSE FOOD IS IT, ANYWAY?

“Some days I think about whether my tolerance for spice is a metaphor for my ancestor’s resistance. Colonizers fought wars over our spices, but didn’t know how to use them.” — Neha Vashist, Hungry Zine

Why are food magazines so bad at representing food? It’s a question Edmonton duo Kyla Pascal and Kathryn Gwun-Yeen 君妍 Lennon have chewed over many times.

Each has a lifelong connection with food. Pascal, a maker and community-builder of Métis-Dominican descent, spent years working in the Edmonton food scene. Gwun-Yeen Lennon, a poet of Cantonese-Irish ancestry, currently works on food policy as a city planner.

Their lineages differ, but they share Edmonton as a place of birth, a commitment to food justice, and family roots in farming — though their ancestors occupied different sides of the globe.

Craving better representation, they took matters into their own hands and created Hungry Zine, a community-focused zine series centering radical food stories and voices absent from traditional media: cooking while poor, while racialized, while a child of refugees, or as a way of connecting to your ancestors.

A diverse lineup of contributors give an intimate look into their kitchens and histories in Hungry Zine. Some stories echoed my own food experience as a second-gen kid, while unfamiliar tales offered new perspectives and valuable lessons.

In her contribution to Hungry’s debut issue, “The Edible is Political,” Bhaswati Ghosh talks about the resourcefulness of her family, who lost everything in the violent aftermath of India’s independence from Britain. “Food was seldom wasted in our house, even when it got spoiled,” Ghosh writes. “Instead of trashing leftover food, spoiled milk was turned in chenna (soft cottage cheese)”. Other examples of metamorphosing dishes follow. Though Ghosh’s family’s values are born out of trauma, they offer wisdom worth considering.

“When you’re a refugee picking up pieces in a new environment, food becomes a part of your layered political dynamic. It demands a pragmatism that eschews sentimentalism in favour or economy,” writes Ghosh. It’s a recurring theme among diasporic food writers. Traditional dishes served at home might look different from those seen in the motherland, having been adapted to use whatever ingredients and spices are available in a new country. But the spirit of the dish remains.

Pascal and Gwun-Yeen Lennon have extended Hungry Zine’s mission beyond the printed page. The pair created holiday food boxes this year that highlighted tasty treats made by local BIPOC chefs and food makers. The boxes included goodies like hot sauces, drinking chocolate, jams, teas, and of course, a copy of their zine.

FOOD ISN’T JUST FOOD

“Friendship brews in the coffee pot and family swims in the strawberry juice.” — Katie Turriff, “Soup ‘n’ Bannock Thursdays at the Waterloo Indigenous Student Centre”, Hungry Zine

Joumou is a Haitian soup — and so much more. In the 17th century, enslaved Africans were forced to cook joumou (pronounced “djhzoo-moo”) for enslavers, and forbidden from eating it themselves. Today’s Haitians cook joumou for themselves and loved ones, as a powerful symbol of liberation. It’s such a precious representation of struggle and freedom from colonization, that it was awarded “protected cultural heritage status” by UNESCO.

“Food is sustenance but it’s often so much more than that — it’s culture and history, it’s a part of family and memory, it exists alongside pain and trauma, and it can be an art form that can encapsulate all of the above,” says Lim.

Lim is among a new wave of creators using food zines as a way of reconnecting with their culture of origin.

“I’ve had my share of identity crises. Not being able to speak my mother tongue and being surrounded by people I couldn’t fully relate to, food became a way for me to access those histories, memories, and traditions,” says Lim.

Food is a powerful vehicle for connection. Connecting with our ancestors, family, friends, community. But when we’re alienated from where our food comes from, we’re not just missing out on delicious food, we’re missing out on connection. Connection to the hands that labour so that we enjoy bonding with loved ones over a meal. Connection with the earth that provides all that it does. And genuine understanding and appreciation of people and cultures who we might otherwise consider strangers.