I stumbled upon zines in the late ’90s as an angsty youth who frequented $5 punk shows where zines were being traded as an early form of social media. These haphazard little books on merch tables felt like treasures in my hands, like a secret that I was lucky enough to stumble upon: words straight from the source as pure as an intimate conversation had in person.

Zines were a breath of fresh air. They opened my eyes to raw and realistic words on subjects such as politics, how-tos, physical health, and often intimate stories of mental health struggles. These words were a lifeline and they helped build the basis of my own sense of self and politics. Even today, I find myself hunching over each new zine, as if I might miss a whisper if I’m not close enough. Zines were and always have been versatile and alluring.

During the winter of 2018, Canadians saw the heartbreaking verdicts of the Tina Fontaine and Colton Boushie trials. I wish I could say that the “not guilty” verdicts rendered to the perpetrators responsible for the deaths of these Indigenous youth were surprising. But they were not, especially to anyone who had taken the time to really think about how Indigenous people are viewed, treated, and valued in Canadian society. Despite anticipating these verdicts, it didn’t mean that my heart wasn’t overwhelmed by sadness and a deep feeling of helplessness. My brain was full of anger and questions about how this violence and dismissive tone could still be so aggressively alive in this country? It is a hard thing to try to turn sadness and despair into something constructive, something that can feel like change. The future felt bleak. During this dark time, I felt so small and beat down, I kept asking myself if it was even possible for one person to be able to do anything that could help. I eventually came to see that while I couldn’t change everything in one grand gesture, I could start small and perhaps challenge and change the dialogue happening in my community around Indigenous issues.

So why zines?

I get this question constantly.

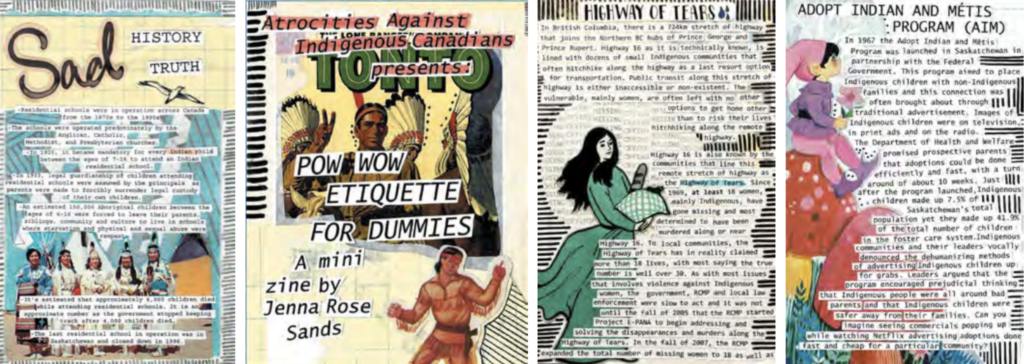

While I was in this cycle of feeling helpless, my mind kept coming back to zines as a possible medium to educate and pour my exhaustion into. There are plenty of existing texts and resources out there that discusses Indigenous people and the atrocities we have endured. I am not communicating facts that have been hidden, it’s all out there already. Despite this wealth of information I know many are never going to pick up the Truth and Reconciliation Report and read through it. There are still such deep prejudices held toward Indigenous people that it’s not realistic to think that people with these prejudices will seek out a book that is a large time commitment. We are living in a time where supporting an issue or group of people is often done in the form of clicking “like” and sharing across social media. I wanted something dynamic, quick, visually engaging, but also with content that was a punch to heart. Zines are tangible, artistic, accessible, and, most importantly, the zine I would create would be my own anger direct from the source, not edited by a panel of people, no one to say I was “too angry” or to question my need to tell these stories.

Zines have been the perfect medium for my rage. I lovingly describe this project as being born out of my emotional exhaustion over the current state of Indigenous affairs. This zine series strives to get people to understand what the real history of Indigenous people looks like, and hopefully see that what is currently happening has always been happening in some form or fashion since First Contact.

While this series has many more issues to touch on, I look forward now to a future that sees my people thriving. Miigwetch.