“The beautiful thing about mushrooms is that many of them have lots of great names,” game maker Jeeyon Shim tells me. Mushrooms constituted the first topic of conversation in our breezy semi-decade-long friendship, obviating the need for stiff introductions.

“The beautiful thing about mushrooms is that many of them have lots of great names,” game maker Jeeyon Shim tells me. Mushrooms constituted the first topic of conversation in our breezy semi-decade-long friendship, obviating the need for stiff introductions.

In 2021, Jeeyon posted a series of threads on Twitter about mushroom foraging. Candy Caps, true to their name, carry the aroma of maple syrup. “I’m torn between making candy cap sable cookies to keep in my ice box or candy cap lace cookies to eat all at once,” Jeeyon tweeted. On the other hand, consider Witch’s Butter. Its name does a lot for it: the simple act of naming it “Witch’s Butter” transfigures it from a streak of urine-lurid forest slime to a gorgeously thick, cheese-like layer the colour of fairytale sunshine. Unfortunately the name is deceptive. The fungus is apparently quite flavourless, Jeeyon once informed me.

I don’t think Jeeyon intended it, but our discussion about mushroom nomenclature carries a curious resonance with her style of RPG design. In her work, Jeeyon tends to eschew the complicated stat tables, long lists of character abilities, and involved dice-mathematics that typify “crunchy” tabletop roleplaying games. After all, Jeeyon’s first TTRPG experience was through Dread, Epidiah Ravachol’s celebrated Jenga tower-based horror game. “This really influenced how I thought about any kind of game that essentially consists of make-believe for adults,” she tells me. To new-gamer Jeeyon, there was no Dungeons & Dragon, no Shadowrun: there were only rules-lite story games.

Today, Jeeyon’s most celebrated contributions to the field come in the form of contemplative journaling games. In them, players might spend long, loving hours over seemingly small details like character names in order to craft powerful symbolic resonances. In Jeeyon’s work, things like names, often trivial in games, might matter a great deal.

What’s going on with TTRPGs?

Once there was Dungeons & Dragons —

Scratch that. Once there was Charlotte and Emily Bronte writing letters to each other, pretending to be insurrectionists and heroines —

No, that isn’t quite the beginning of the story either, is it?

Once there was a person — of an age, nationality, and historical epoch of your choice — who decided to play pretend. Once there was imagination.

Humans have been roleplaying for fun for as long as humans have been human. It didn’t start with Dungeons & Dragons, with Chainmail, or Kriegspiel, or any of the other (war-themed) games your nerdy friend can think of. It started with some unknown human going, “What if I weren’t me?”

And just as tangled and multiform as the origins of roleplaying games is the tabletop roleplaying game (or TTRPG) scene today. You have the heavy hitters like D&D, Pathfinder, Vampire: The Masquerade, and Shadowrun, often accompanied by lavish Actual Play podcasts or streams. You have indie darlings like Bluebeard’s Bride, which masterfully highlights the horrors of domestic violence and intimate-partner abuse, Dialect, which shows us how language death and culture death are inextricably linked, or Wanderhome, which evokes the gentle gambolling of woodland creatures. And you have the great, teeming mass of tiny one-page games on platforms like itch.io, or lyric games, of games that are untested, of games that were patched together in 48 hours for a game jam, of zines and pamphlets, of orally-transmitted playground games.

A far cry from the ‘80s and ‘90s, today’s TTRPG scene is as diverse as the people who constitute it. You can find indie games of every stripe, exploring the joy-ful, the dark, or the fantastical aspects of humanity. Today’s TTRPG scene is as expressive an artform as any in the history of humanity.

In Shim’s The Last Will and Testament of Gideon Blythe, where players explore questions of family, identity and inheritance after discovering in their father’s will a promise of a priceless boon, your protagonist’s name powers the story’s thematic heart. “Which of your elders are you named after?” she asks. “Write your elder’s name under your own on the first page of your album, with black ink,” followed by, “Draw a box a few inches in width and height, with black ink. At its very center, using white ink, write your elder’s worst trait, which you share with them.” Here, the simple act of naming connects your character directly to a hidden, unpleasant legacy, a legacy that you yourself are complicit in creating.

Jeeyon’s games often ask players to tackle such heady topics. And it’s the nature of solo TTRPGs to afford such emotional explorations. Free from the scrutiny and judgement of table fellows, you’re granted the liberty to craft narratives infused with personal hopes, fears and knowledge. No one can “correct” your interpretation of text or prompts. Funnily enough, mushrooms can be like that too. Lactarius camphoratus, one of several species of mushroom Jeeyon might recognize as her prized, mapley “Candy Cap” mushroom, is also known as the “Curry Milkcap.” The sugary scent cherished by Jeeyon has been interpreted by others as the smell of curry. And who are we to naysay their personal experience?

Jeeyon’s games are all about that personal experience. Take this player prompt from Jeeyon’s The Shape of Shadows: “Close your eyes. Think of an owl. What is the first defining characteristic you see in your mind’s eye? Write it down and underline it in the Scratchpad section of your journal, and underneath describe the whole bird in as much detail as you can see in your mind’s eye.” I have only vague, generic ideas about what an owl looks like, and when I playtested this portion of the game (to prepare for my contribution to it), I was perfectly content with my own, rather multicoloured rendition of an owl. It was Pride season, after all.

Jeeyon’s games are all about that personal experience. Take this player prompt from Jeeyon’s The Shape of Shadows: “Close your eyes. Think of an owl. What is the first defining characteristic you see in your mind’s eye? Write it down and underline it in the Scratchpad section of your journal, and underneath describe the whole bird in as much detail as you can see in your mind’s eye.” I have only vague, generic ideas about what an owl looks like, and when I playtested this portion of the game (to prepare for my contribution to it), I was perfectly content with my own, rather multicoloured rendition of an owl. It was Pride season, after all.

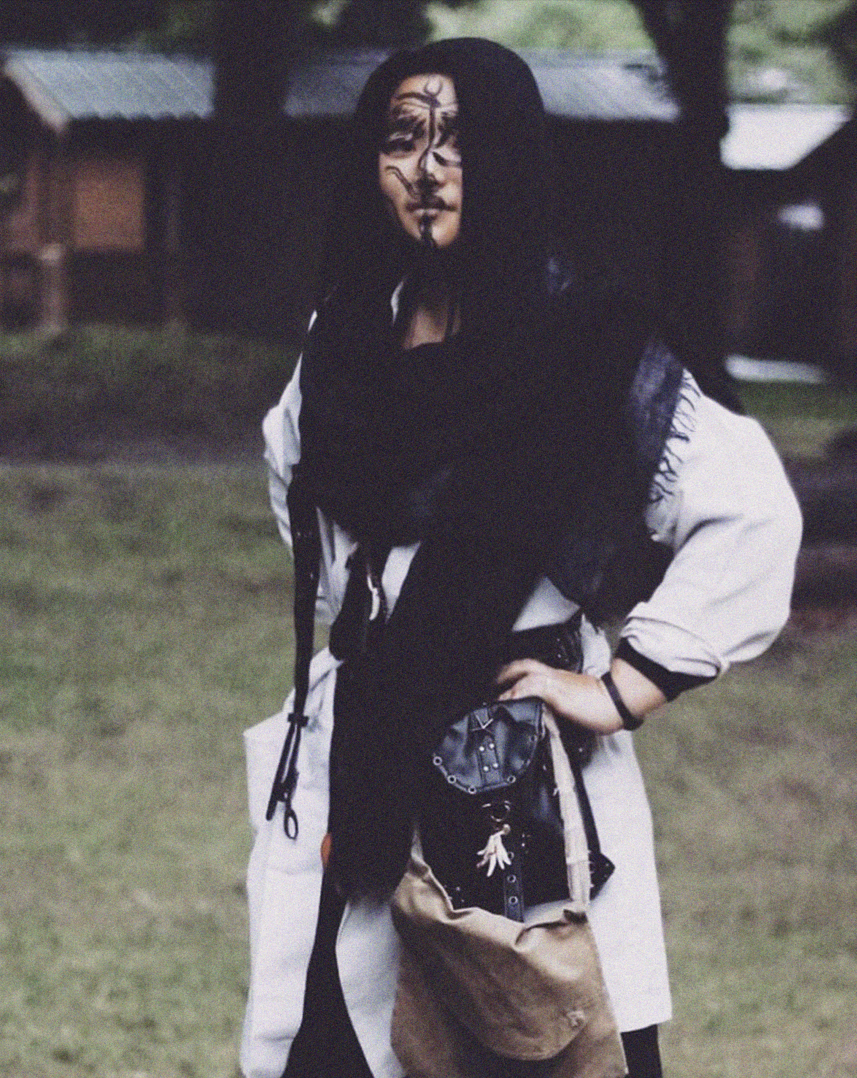

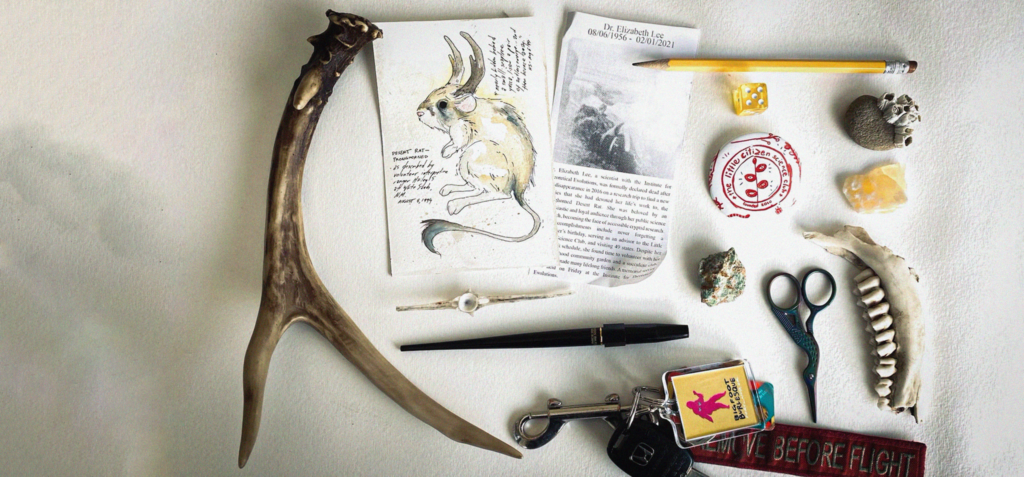

In this age of online sharing, it’s perhaps not surprising that many of the personal experiences of Jeeyon’s games started their own social media trend. Field Guide to Memory, a solo RPG Jeeyon co-designed with Shing Yin Khor, asked players to build out the physical journal they were playing with and populate it with photos, drawings, and samples they might find in the wilderness. The game birthed a popular Twitter hashtag (appropriately #FieldGuideToMemory) with adherents including luminaries such as famed Firaxis Narrative Director Cat Manning, and best-selling, award-winning co-author of This Is How You Lose the Time War Amal El-Mohtar. This response to Field Guide emblematizes two of Jeeyon’s design philosophies: community-building and crafting.

Community-building has long been a part of Jeeyon’s life. Even with mushrooming, Jeeyon frequently poses questions to a “nice” mushroom group, and observes with awe a “very, very mean mushroom ID group who I am scared of but crave validation from.” And Jeeyon ventured into game design through her experiences at children’s outdoor education programmes. Her first were live-action role playing games designed to promote land stewardship among the kids. Kids learning together how to work with the natural world, and what our roles and responsibilities as part of the human community meant about our interactions with nature. This connectedness to other people was crucial to Jeeyon’s re-entrance to games after a long break: “The social gathering aspect was reintroduced to me!” she says. So Jeeyon and Shing coined the term “Connected Path Game” for Field Guide, referring to the pathways that link players to the creators and to each other. In a sense, Field Guide was designed to be anything but solo.

Crafting too, comprises part of the Connected Path ethos. “Connected Path games are the process itself being shared,” Jeeyon told Polygon’s Nicole Carpenter. Jeeyon adored the loving, handmade process that players put into the game. Players took pains to choose just the right notebook for the game, to design stamps and stationery for the fictional institutions within the game, even to cook the recipes included in the game. “I’m always going to return to tactile games as my keystone,” Jeeyon tells me.

In fact, many of Jeeyon’s crafting hobbies directly relate to game design. She speaks to me of wood-carving and whittling, and how it teaches habits that are directly translatable to creating games. “You can’t force the grain,” she says, dispensing a piece of writing advice when asked what carving taught her. “If you can’t work with your own currents, you’re just fighting yourself.”

“Working with one’s own currents”, unfortunately, has become a dominant theme in Jeeyon’s life in a painful way. While COVID isolation hit her just as hard as anyone else (games helped her stay grounded: “Playing Band of Blades with you & Ross Cowman got me through the pandemic!”), Jeeyon has become disabled due to long COVID symptoms. She can no longer enjoy much of her life in the same way as before. The experience made her think, of course. “Disability is a marginalization anyone can enter regard-less of background,” she asserts.

Consequently, Jeeyon is attempting to put accessibility at the forefront of her new designs: “I want to make things anyone can play and make room for in their lives.” For quite a while, the tagline for Jeeyon’s body of work has been “games that face the world,” referring to the way she makes players look at nature and their surroundings. The tagline remains, but her experience with disability has lent the tagline new shades of meaning. Now, Jeeyon wants to give those who live in isolation, or those who live with disabilities and difficulties a way to face the world through her games. “This is going to happen to a lot of people,” she reasserts.

But her words don’t carry pessimism. After all, if working with nature has taught her anything, it’s that people are resilient. We can evolve. Despite a pandemic, despite periods of artistic block (some-thing Jeeyon is no stranger to), despite a substrate of death, disease, climate decline and geopolitical turmoil, humans can still create connected paths of art, of feelings, of longings, of dreams—can still send out tendrils of life into the earth, into the air.

Much like mushrooms.

Sharang Biswas is a New York-based game designer, artist, and writer. He has worked on boardgames including Mad Science Foundation, Holi: Festival of Colors, & Sea of Legends, as well as tabletop RPGs including Avatar: Legends, Spire: The City Must Fall, and Jiangshi: Blood on the Banquet Hall. Sharang has won IndieCade and IGDN awards and showcased games at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, and the Toronto Reference Library. He has taught game design at Dartmouth, NYU Game Center, Parsons, and more.