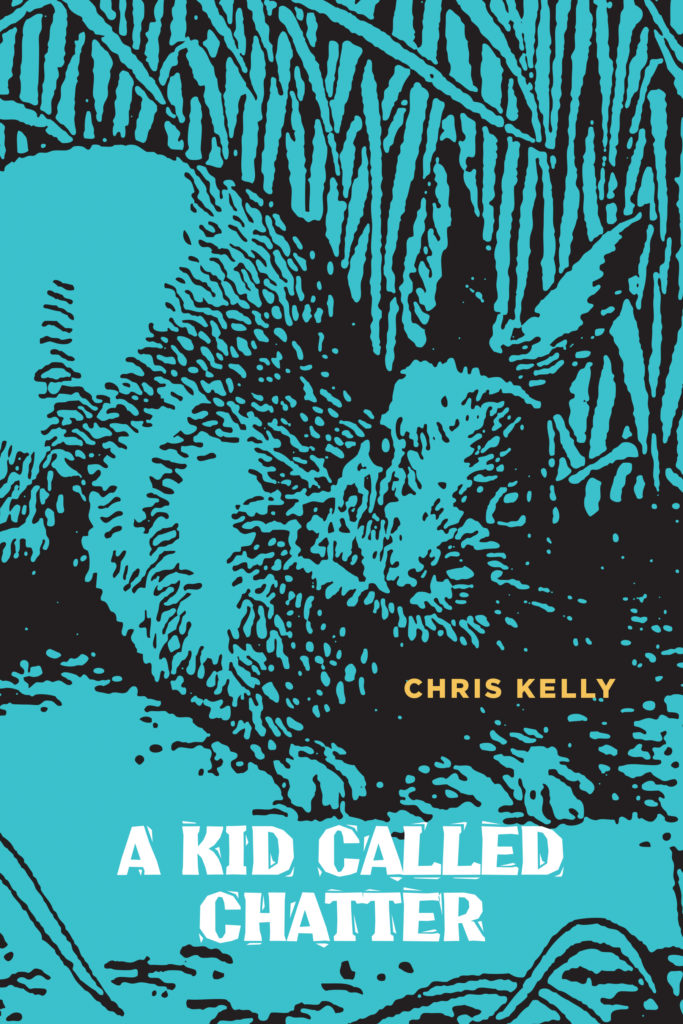

A Kid Called Chatter

Chris Kelly, 326 pgs, University of Calgary Press, press.ucalgary.ca, $24.99

The western is a uniquely American genre, born of our southern neighbour’s relationship to westward expansion and all the cultural baggage that goes with it. Canadian westerns must contend with this unspoken priority while struggling to carve out a frontier space all their own.

Chris Kelly’s A Kid Called Chatter does just that, working with a liminal contact zone not between east and west, settlers and First Nations (who are conspicuously absent in Kelly’s world), but between the rough-and-tumble settlement town of Farrow and the band of kids who live in the woods bordering it. Chatter, an orphan gifted with the ability to sense and comfort dying animals with his hands, moves between these spaces, taking up alternately with Lou, a charismatic conman who sees Chatter as something like a son even while profiting from his gift through a series of revival-style tent healings and ill-fated scams, and Azalea and her band of rebel orphans fighting another orphan gang for safety and space in the forest.

The name is ironic, as Chatter talks little and thinks even less. The reader is left to fill in the gaps and make sense of the value of Chatter’s gift in this heavily symbolic world where everything is an allegory of vengeance or forgiveness, faith or its absence. The book is weighted with self-consciously poetic prose creaking with the effort of its own execution (“He imagined the distance from his wrist to a human heart, and used that as his measure”), but that muscular prose falls short of the heavy lifting necessary to build living, breathing characters to fill its pages.

Westerns are populated with larger-than-life characters, but children are notoriously difficult to write convincingly. Kelly’s Chatter and his orphan companions are adult minds in small bodies, making grave enigmatic statements while stone-facedly witnessing the world’s cruelty and violence with wisdom beyond their years. They lack that uncanny kid-sense that shines through in say, Stephen King’s work, leaving the reader cold with the effort of caring for them. Everything in the novel feels somehow rehearsed or second-hand, like a kid trying on his big brother’s shoes. But maybe that’s what it’s like writing a Canadian western, trying to make yourself at home in a genre too big and worn out to house these small eccentric dreams birthed north of the border, where nothing fits quite right.