By Melissa Keyser & Jonathan Valelly

In a new book with ECW Press, Helena Moncrieff zooms in on foraging urban fruit trees. Inspired by organizations like Not Far From The Tree, which harvests urban fruit trees and splits the haul between community groups and the homeowners, The Fruitful City examines our relationship to waste, cities, hunger and, of course, fruit.

Moncrieff points out that way too much of the potential urban fruit harvest, like apples and berries, simply goes to waste. So much so that there’s little reason to worry about overharvest or beating out birds and other animals who can reach higher than humans anyway.

“There are 1.5 million pounds of fruit produced in Toronto alone every year. That’s a lot,” says Moncrieff. “How much of it are we picking? We don’t know, but I would say not much at all.”

For Moncrieff and Not Far From The Tree, this underutilized harvest can be a critical resource for addressing food security and inequality. Looking to the food sources all around us is more important than ever.

And they’re not the only ones. Foraging, also known as wild harvesting, is as old as humankind. But as factory farming and grocery stores increasingly disconnect people from their food and natural resources, the DIY community and so many others have renewed popular interest in gathering plants, berries, nuts and other naturally occurring, wild resources.

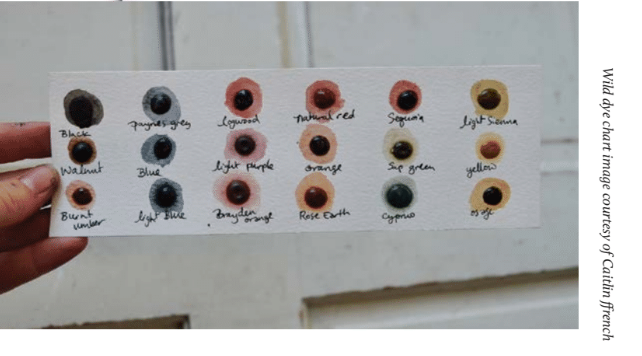

Caitlin ffrench, an independent textile artist based in Vancouver, uses foraged wild plants and weeds as both the medium for her artwork and the art itself. ffrench creates botanically-based pigments and teaches wildcrafting workshops throughout Canada.

She learned how to work with natural dyes at school, but foraging has always been a part of her life. “Growing up, my father hunted and my mom collected fruit from an orchard and would preserve the bounty. Growing plants and foraging for edibles just made sense.” Some of ffrench’s favourite foraged materials are tansy, which she uses to create shades a green-yellow colour, and black walnuts, which produce brilliant shades of earth.

“Because I’m not consuming the plants, I can harvest from the side of the road, from alleyways, and from forgotten spaces around the city,” she says. “Brake dust, garbage, car exhaust and the like don’t matter when all you’re looking for is pigment!”

ffrench makes sure to harvest as ethically as possible. That means “not to take the first plant I see, because it may be the last, nor the first of the season. I don’t take the first blossoms of the year because those are foods for pollinators, and I stop collecting flowers around the Harvest Moon or the Autumn Equinox and leave those for wildlife.”

Indeed, many artists and DIY foragers alike are looking closely at the political stakes of finding food and making urban agricultures. Horticultural Counterpowers Zine, based in Vancouver, is what creator Madison calls “a zine about how plants figure, metaphorically and literally, within Marxist conceptions of urban space. It’s part a field guide, a reference, a map, and a handbook to the poetics and erotics of plant life in the city.”

When Horticultural Counterpowers first started, Madison was workingthrough ideas both about plants and urban space. “I played around with some ideas and content that looked a lot closer to how urban foraging zines tend to look,” she says, “gardening/moon calendars, writing about picking flowers from alleys, info about culinary and medicinal uses for urban plants.”

“But, just celebrating plants wasn’t quite clicking with the political frameworks and models, especially Marxist ones, that I was getting more into at the time,” Madison says.

She aims at helping nourish the foraging movement “in terms of useful political action or organization.”

Madison’s zines make sure to consciously address the way settler colonialism is at play in homesteading or other farming projects on unceded land. She wants to open conversations about how growing and harvesting plants can still be an act of political resistance.

For Dionne Paul, a Sechelt Nation and Nuxalk Nation artist based in Vancouver, there is a simultaneous joy and anxiety at seeing an increased enthusiasm for foraging both in the forest and in urban settings.

“It’s super trendy, which I appreciate, because more people should be going back to the land and harvesting medicines in a real true way instead of pharmaceuticals, whether they’re First Nations or not,” she explains. “But it’s also scary to think about overharvesting … I don’t want our land trampled.”

Paul, who has included traditional cedar bark harvesting in her role as an artist and teacher for more than two decades, recently found an excess of stripped trees in her favourite forest.

“I had a sinking feeling of dread,” she remembers. “I became really conscious and aware of who I took in the forest, who I taught, and what are my motivations.”

As enthusiasm for foraging grows, Paul reminds new foragers who are gathering on traditional lands to ask for permission from the authorities of the local First Nations, and to be conscious of your role if you are a settler or from another Nation.

Lori Snyder, a Métis artist and gatherer based in B.C., echoes these sentiments.

“People can be so blind to nature, and we’ve been colonized away from that relationship,” says Snyder, who also runs workshops. “It’s really important that we all start to go, ‘What is our story, how did we get here?’”

For Snyder and so many others, harvesting is not only a rural or forest activity — we can, and ought to, reconnect with the plants all around us in the city.

“As soon as you walk outside your door, you can start engaging in this relationship,” says Snyder.

Indeed, reframing our relationship to plants sits at an intersection between personal practices and art, and broader possibilities for collective movements and well-being. As Dionne Paul suggests, let’s get in touch with our backgrounds, our land, and our motivations.

And, she adds, “most importantly — get excited!”

Happy foraging, friends!