Zines — you love to make them. But what if you could make them into something more? Ever wish you could just smush your zine into your Nintendo until a video game popped out?

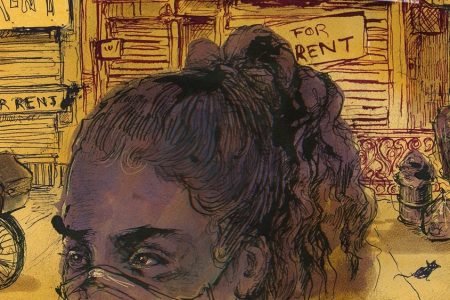

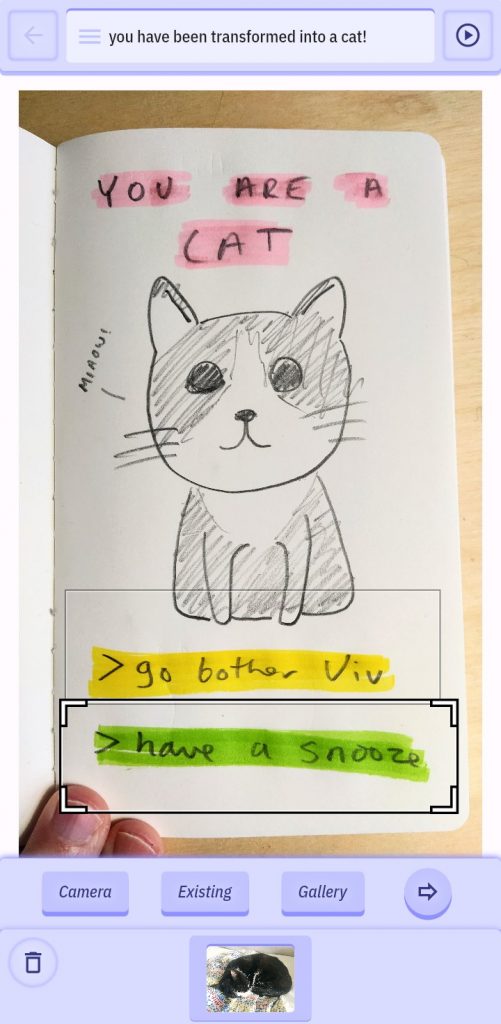

v buckenham, a programmer, toolmaker, zinester and former member of the Pokémon Go studio Niantic, is tinkering on the perfect program for you: Downpour. Using just your smartphone, Downpour lets you transform any zine, photo, drawing or material into a piece of a choose-your-own-adventure game, linking pages and prints together into a quest of your making. I caught up with buckenham to discuss their latest creation and the growing relationship between zines and indie games.

What prompted you to make Downpour?

It’s an idea I’ve had kicking around for a while now, and it comes from a few different places, as these things do. But a pretty formative experience was in curating the Now Play This festival in London — we showed a lot of non-commercial or unusual games to a general audience, and a thing that always seemed to go down well was when visitors could get their hands on something and actually make a game themselves (or a zine! we had a zine-making area one year). But finding tools that were approachable, friendly, that could be used by people of all ages, and that actually let people make the whole game themselves — that was always hard.

One year we had a “flatgames” workshop, which worked really well. People drew on pieces of paper, and they were scanned in using a neat phone-based tool by Mark Wonnacott, and then turned into games by a little crew of developers working in Unity (an easy-ish to use game engine). That was obviously great in terms of letting visitors create parts of the games and see the full process — but it still didn’t let them make the game end to end.

It seemed to me there was no technical reason that should be the case, and that it would be pretty great if an approachable tool existed that let people complete the whole process.

The first thing I think of when looking at Downpour is turning zines into games. Was a zine-to-game pipeline your intention?

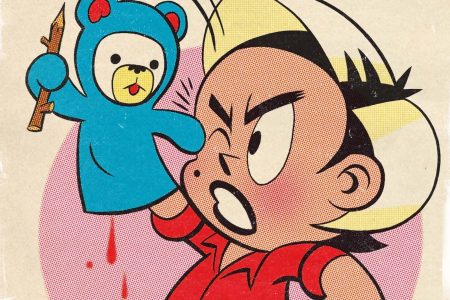

It’s definitely something I’ve been thinking about! I’m definitely trying to make something that can take advantage of that kind of collage style; something where you can spend most of your time drawing on paper, posing for photos, being in the world and not within a screen, but then still have a videogame at the end of it. And I’m definitely inspired by Nathalie Lawhead’s Electric Zine Maker, which tries to bring some of that scrappy energy to the digital domain.

You mentioned how you were inspired by flatgames. What is a flatgame?

Flatgames are a form originally created by Llaura McGee and Breogan Hackett — they’re an attempt to strip back a lot of the difficulties and complexities of game-making and focus on something more raw and personal. They’re typically games where all the graphics are on one plane, where there is no (or minimal) collision, typically made with collaged assets which show the traces of their making.

It’s a really inspiring form — although, as inspiration often works, I was inspired by the possibilities but also my frustrations with it. Making a flatgame myself and finding I had to spend most of my time still grappling with technical bullshit and writing little bits of code to get the behaviour I wanted — all stuff that I could do, but that detracted from the approachability of the form. As someone who enjoys making tools, that also felt inspiring and felt like an opportunity to make a tool that could help bridge that gap.

Are there any existing similarities between print zines and small games?

Totally — having made both, I think the creative process for them is really similar. You start with an exciting concept, then there’s a painful period in the middle where you realise just how much stuff you need to make for the exciting concept to work, and then hopefully, eventually, a real feeling of satisfaction at the end when the thing exists and can go off and be played or read by people and have its own kind of independent life without you. And I think they exist in a similar kind of cultural space, too. Each has people who care about them, who make them and play them and exist in community with each other. And often, they’re the same people who care about both.

Why is it important to create accessible programming tools?

I want to make things that lots of people use. That’s why I make accessible tools — because there’s a real joy in creation, and right now, that joy is only accessible to people with a certain set of skills, enough time, the right kind of equipment, etc.

Why do you need to have a computer to make a video game? Just because there aren’t enough tools for making a game with your phone. I want to share that joy of creation with more people and see the things that these people will make.

If someone mostly experienced with zine and comix making wants to try their hand at game development, what are some tools they should check out?

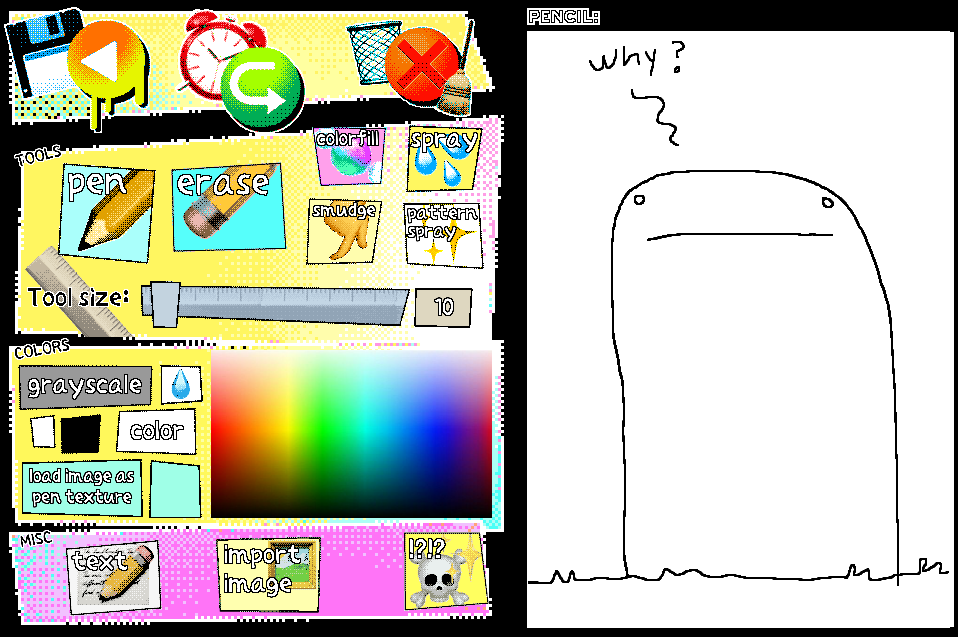

Here are a few tools I love that you can try out. They all export for the web (so people can play your games!), will run on a low-end computer and are free (except sok-stories).

If you think of yourself as primarily a writer of prose, then Twine is a great tool for making interactive text stories — its core is writing passages and linking them together in a hypertext-y way, but with a lot of expressive features on top of that for controlling animation and the way links should operate. Or, if you’re a writer, but you mainly think in terms of scripts and characters being sassy to each other, then Ink is great — designed for making rich conversational branches. It’s mainly designed for integration into larger projects but has a web export that works just fine.

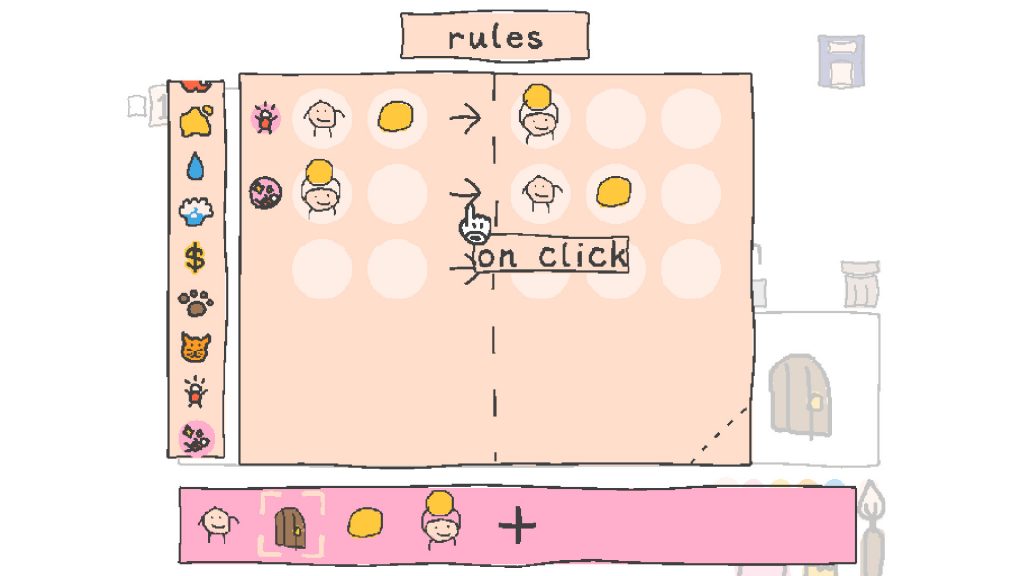

If you want to make a little pixelated world with a guy running around it — Bitsy is the way to go. And if you want to draw and design a little system for players to explore — something like seed plus water becomes a flower, and so on — then I have a lot of love for sok-stories. This is the only one that costs money. It’s $3. And if none of those strike your fancy, then I can definitely recommend the Tiny Tools Directory, which has a lot of interesting tools available.

Downpour will be available for iOS and Android later this year. You can check it out at downpour.games.