Features

No Cure In Sight: Grant Ionatán on COVID, Isolation, Disability and Against Forgetting It.

A lifetime of alienation from my peers and reluctant obsession with death had turned me into some kind of stoic mutant, able to see in the metaphorical dark. It felt good to say that I had been preparing for this my whole life, whether or not it was true.

How Club Quarantine Kept the Party Going

Club Quarantine became the place to be when you couldn’t really be anywhere at all. With lessons from lockdowns, the party ensemble plans to make partying more accessible to all.

Zines Take TikTok

When Bre Upton first joined TikTok it was simply as a means to curb quarantine-born boredom. Now her tutorials on zine making have over six million views. How 'Zinetok' is uniting DIY-ers around the world.

Shut Up and Vibe: Racer Trash’s Movie Joyride

The Racer Trash film collective is dead, but its tire tracks remain streaked across the fringes of cinema.

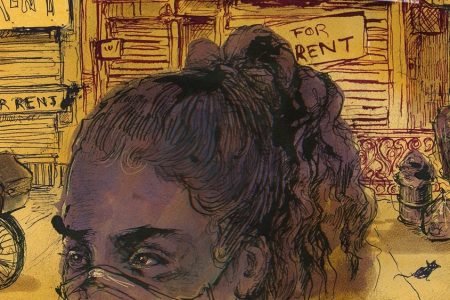

Maximillian Alvarez on The Work of Living, COVID and The Unfathomable Loss of One Million Lives

"How can we quantify all that’s been stolen from us? How can we forgive the failures of our governments and our economic system whose callousness, greed, and jingoistic competitiveness made this all so much worse than it could have been?"

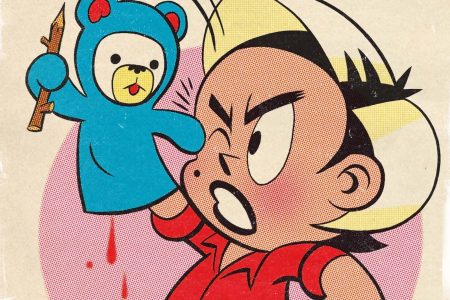

Jay Stephens On Their Creepy, Quirky, Demonic Comic Dwellings

We chat with Jay Stephens about small town mysteries, the gruesome side of Casper and their Doug Wright Award winning horror series Dwellings.