illustration by Patrick Burgomaster

The internet is a wonderful and terrifying place to be an artist. Anyone can create something, scan it, and put it online for the world to see. If the right people find it, you can develop a community of fans, and maybe even make a bit of money. But in the wrong hands, your work can take on a life of its own.

That’s what happened to Matt Furie, the creator of the now-notorious character Pepe the Frog, which became a bizarre symbol of the ‘alt-right’ men’s rights activists who supported Donald Trump’s run for presidency. Furie, a Hillary Clinton supporter, never intended this to happen with his a sweet little googly-eyed stoner frog, who first appeared in a 2005 web comic.

A few years after that first appearance, frames from Furie’s comics featuring Pepe started being used as a meme on sites like Reddit. This meme eventually morphed to include the ugly, hateful and often violent language of the Trump campaign, and in the fall of 2016, the Anti-Defamation League officially recognized Pepe the Frog as a hate symbol.

Since then, Furie has tried to reclaim his Pepe, with a “#SavePepe” campaign, and comics on sites like The Nib that comment on what happened.

“It’s the worst-case scenario for any artist to lose control of their work and eventually have it labelled like a swastika or a burning cross,” Furie told the Guardian newspaper in November of last year. “I had to step up and speak on the cartoon frog’s behalf.” Unfortunately, for both Furie and Pepe, it’s already too late.

Furie’s story is a particularly extreme example, but the internet has always been double edged sword for artists, especially visual artists. On one hand, it’s a calling card with a low barrier to entry: anyone can scan their work and upload it to a website where it is potentially discoverable by the whole world, and it’s a boon for an ongoing cultural conversation. But once an image is online, it is incredibly easy to copy and share, which can obviously be beneficial to the original artist if they’re properly credited. Unfortunately, that’s a rare occurrence. Comics and photographs frequently go viral without the original artists’ name attached, as if they’ve sprung fully formed out of the ether of the internet. That’s why copyright laws allow for “fair dealing” (more on that later). But finding the line between appreciation, appropriation, and reinterpretation is an ongoing challenge.

For Canadian artist Ryan North, who has been publishing his webcomic Dinosaur Comics online since 2003, the line between a remix and a rip-off is creative intent “and whether they’re trying to sell it,” he says. “That’s a clear line in the sand you can draw between fan work and knock-offs.”

Remixing isn’t a problem for North — in fact, he actively encourages it, and has a page on his site with links to fan-made Dinosaur Comics tributes. “That’s super kosher and I love it. There’s nothing wrong with that,” he says. “It’s always a pleasure to come across that in the wild, like if someone’s made a Dinosaur Comics reaction gif or something. That is almost uniformly a positive experience.”

More problematic for North is the issue of merchandising, because he makes a large part of his living off of the Dino Comics merchandise (classic slogans include: “Feelings are boring, kissing is awesome.”), he sells through the website TopatoCo, which specializes in distributing merchandise for independent creators.

But online, where copying an image is as simple as a couple of clicks of a mouse, creating knock-off merchandise is easy.“I’ll make a t-shirt design, and someone will rip off that design. And this happens all the time, and it’s so depressing that it keeps happening,” says North. “And it keeps happening because companies are built on it.”

The internet is rife with sites that allow you to make custom merchandise, like Zazzle, Red Bubble, and Spreadshirt (North says he has recently had to deal with an infringement issue from that last one). — You upload an image, and these companies will print it on a t-shirt or a mug. But these companies seem to take for granted that the images people upload to turn into shirts or socks or bibs will be their original artwork. There’s a box you have to click when you upload the image that states you own the copyright — but no one actually checks. People lie, and the companies themselves play dumb.

“And then when you write them and say ‘hey you ripped off my work,’ they say ‘oh it’s not our fault, they checked off the box,’” explains North. “Maybe in 2003 that would be a reasonable response, but there’s such a thing as reverse image search now.”

North says he does a revers image search on his designs every few weeks, and he has to write a takedown notice to a company once every couple of months. “So it happens a lot, and you don’t notice it a lot of the time,” he says. It’s one of the more annoying parts of his job.

This kind of insidious image theft isn’t limited to fly-by-night online merchandising companies , and it’s not a new phenomenon. Nova Scotia-based textile artist Blythe Church had a disheartening experience with retail chains when a friend sent her a picture of a toy monster doll being sold at Winners that was almost identical to dolls that Church herself had been making and selling at independent shops. Unfortunately, the dolls sold out at Winners before Church was able to get her hands on one, so she was unable to obtain any evidence that would support legal action against the company making the dolls.

“At first I felt flattered and then I remembered all my late nights hand sewing these monsters to fill orders for stores and for craft fairs and it made me so angry,” she says. “I feel really helpless. Chances are that the item was made abroad. Even if I knew who had copied my work, I am a small scale producer and don’t have the finances to take legal action. In this instance watermarked photos wouldn’t help. As somebody making one of a kind pieces from upcycled materials there is little I can do to protect my work. I will definitely think twice about what I share online from now on.”

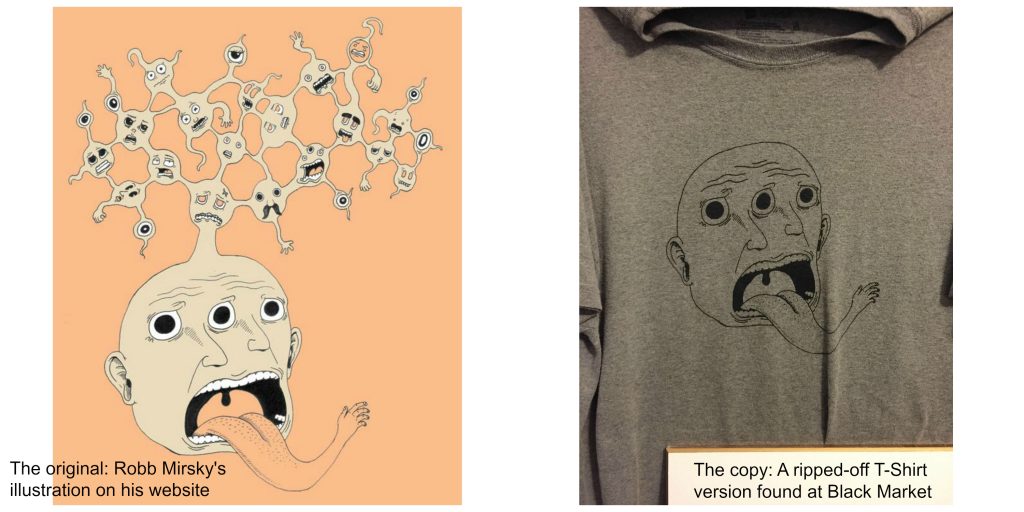

And sometimes it’s not even big chains who are at fault. Designer Robb Mirsky noticed an image he’d designed for a band’s album cover on a t-shirt at Toronto’s Black Market, a shop that specializes in vintage clothing and bootleg band t-shirts. “Basically, I had to hire a lawyer (thankfully, my friend is a good one) and send them a cease and desist letter, buy a shirt off them for proof, and ultimately spend a lot of time, money, and emotion on a situation I didn’t want to deal with in the first place,” says Mirsky.

Artist Eric Kim learned from friends that a graphic designer at a t-shirt company, Freeze CMI, had taken Kim’s illustration of the wrestler Randy “Macho Man” Savage and incorporated it into an ugly Christmas sweater design. Kim hired a lawyer and send a cease and desist letter. But even after Freeze CMI stopped distributing the shirt, knockoffs started popping up online, and trying to keep on top of them became “a giant game of whack-a-mole,” says Kim. “I couldn’t hold the POD service liable because they were only providing a service, and I couldn’t find the person responsible for the work because they would disappear. Just useless.”

Kim is ultimately philosophical about the whole experience. “On the whole, it was an educational moment. I was able to learn about the entire chain of distribution and how the work found a life for itself outside of my sketchbook,” he says. “But it was expensive and painful.”

Even if the end result was frustration, North, Kim and Mirsky are all doing the right thing in trying to enforce their copyright, according to Pina D’Agostino, who founded IP Osgoode, the Intellectual Property Law and Technology program at Osgoode Hall Law School. “There’s a difference between the rights you own and enforcing those rights,” she says. “You could own as any rights as you want, but if there’s no enforcement then it’s (only) as good as the paper they’re written on.”

So that’s step one: if you find your art getting stolen, enforce! But wait – how does one do that, exactly?

“Enforcement of your rights is very challenging in the digital era, and a lot of my work is based on that. Because there’s a proliferation of technology that makes it easier for users to take your work, so in terms of enforcing, really, you have to be educated on what your rights are,” explains D’Agostino. “Because sometimes when people do take your work it doesn’t mean they’re actually infringing on your copyright. It might be perfectly fine and within the realm of fair dealing.”

According to Canada’s Copyright Act, grounds for fair dealing include research and private study, education, review and parody. “But it’s largely open to interpretation,” says D’Agostino. Essentially, “[fair dealing] gives users some options to access works and use them within the limits of the law.” North’s example of print-on-demand t-shirt designs is a clear copyright infringement, says D’Agostino. But the case of a store like Urban Outfitters, selling items that resemble designs by independent designers is less clear-cut.

“Generally, you have copyright on your work and it’s really a substantial part of your work. So that’s the doctrine that’s engaged, ‘substantiality,’” says D’Agostino. But what’s “substantial” is open to interpretation. “Basically it’s on a case by case basis, it’s a qualitative assessment, and it’s not so much the amount, but the quality of what was taken: if it’s the vital and essential part of a work. So a good example is the jingle or refrain in a song. If it’s a very catchy tune, that would be a substantial part.”

And in the case of design, it gets even more complicated because of the “idea/expression dichotomy,” says D’Agostino. “So what that says is you can’t protect ideas, you can protect the expression of the idea. However, what is an idea, and what is the expression is often blurry.” Take, for example, a t-shirt with a heart pattern on it. Because hearts are symbols, they aren’t subject to copyright, but if your design has a very specific colour and size pattern, then you might have more of a case for expression.

But at least in retail-oriented cases like these, as frustrating and time-consuming as they can be, there’s a clear action and result: you send a letter, the t-shirt company stops selling your unauthorized images. It’s even more frustrating to see an image you created go viral…without your name on it.

“It’s hard, because you look at something and now it’s completely divorced from you,” says North. “There’s no way for anyone to easily find out who made it, unless they do a reverse image search, which no one is going to do. It’s hard when you see something that has a million notes beneath it or a million likes, and you think ‘I could have gained some readers from that.’”

It’s particularly infuriating to see your own uncredited creation used as clickbait. Rob MacInnis is a photographer, and if you spend any time at all on social media, you’ll probably recognize the photo from his collection “Dog & Pony Show” which features a group of barnyard animals standing clustered together as though they’re posing for a school portrait. It was published in Juxtapoz Magazine (legitimately, alongside an interview with MacInnis), a contemporary and underground art journal. Shortly thereafter, the photo was shared, uncredited, by a British journalist on Twitter with the comment: “I’d love to be a part of this gang.”

“It was favorited tens of thousands of times, and retweeted just as many,” says MacInnis. “I contacted him and asked if he could add my credit, but you can’t edit a tweet (first problem). He tweeted again that it was me, but very few people noticed the second tweet.”

This photo continues to be an internet favourite, which would be great, except that it almost always appears without MacInnis’s name attached. It was recently included in a list titled “10+ Animals That Look Like They’re About to Drop the Hottest Albums of the Year” on BoredPanda.com (unsurprisingly, the list includes many other improperly credited photos as well).

MacInnis blames social media companies for how their interfaces are set up. “Instagram, Twitter and Facebook make it quite difficult to find the author of a photograph. Our devices are set up to easily share, and nearly impossible to reliably retain authorship,” he says. “ If anyone at any time posts a photo without credit, everyone afterwards will not be able to backtrack and find the originator. It’s like a chain where when one link is broken, every share afterwards, be it ten, or ten million shares won’t include your credit.”

There are countless stories like these. Political cartoonist and Broken Pencil contributor Patrick Burgomaster once drew a couple of comics about the children’s game freeze tag that somehow became one of the first things that came up if someone did a Google image search for the term. “I was laughing as I discovered through Google that a small local news website in the United States had used one of my freeze tag cartoons in an article about freeze tag in public schools,” says Burgomaster. “Normally a magazine like Broken Pencil pays me well for illustrations and cartoons; in this case I did put the cartoon on my blog for anybody to enjoy. But they didn’t even give me the credit, those scoundrels! I don’t expect money for that. After all I did put it on my blog . . . but I might have got some jobs from that, you never know.”

For many artists who have experienced theft, that’s what irks the most — the lost opportunity for recognition and revenue.

The culture of sharing things anonymously, as though the creator doesn’t exist, has to change.

To MacInnis, the pleasure of knowing that millions of people all over the world love his photograph of barnyard animals is tempered by the frustration of knowing how few people care about the person behind the camera (or the freeze tag comic, or the Randy Savage illustration). “I wonder how many people in the world want to know who I am and can’t find me,” he says. “I’ve actually had people in bars show me the image on their phones, not knowing it was me who made it.”

Alison Broverman gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council’s Writers Reserve Program.