Jonathan Valelly

Jonathan Valelly

For centuries, wherever mass defiance and collective power have swollen up, there has been print. That’s true in these transforming times as well, when it remains critical that social movements have their own independent, grassroots and uncensored media. And despite the digital hype, small-scale print publishing offers us unique and strategic tools to forge the path ahead.

As uprisings against white supremacy and state violence expand and sustain across the United States and Canada, DIY publishing can — will — play an important role, alongside a cacophonous (if, necessary) digital arena of ideas. But it will also adapt to suffuse the growing number of bodies and minds in the streets. Far from being displaced by apps and laptops, print is now the very antidote needed to adjust for the weaknesses of web activism — hyper-surveillance, mistrust, noise and barriers to access. Zines will do what code cannot.

This idea is necessary to repeat right now, but it is not new. In her 2017 Zine Philosophy column for Broken Pencil, Chicago zinester Luz Magdaleno Flores of Brown and Proud Press (BPP) describes how she and her crew use zines to build mutual support in communities of colour. Flores, with co-editor Alvaro Zavala, founded ¿Serio? Zine in the aftermath of the Mike Brown protests. While classmates still focused on tepid electoral canvassing, they created something more urgent. Flores also thanks BPP’s Monica Trinidad in the piece, for having illuminated anti-racism’s foundational place in the origin story of zines. They insightfully trace the zine legacy back to activist-journalist Ida B. Wells. Born into slavery in 1862, Wells would spend decades of her life tirelessly publishing anti-lynching pamphlets, travelling to every corner of the segregated South to distribute them at great risk to herself. In May 2020, she was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize

Whatever the scale or scope, this type of self-publishing and its hyper-responsive distribution mechanisms have been priceless in any effective social movement. Zines, pamphlets, affinity journals and newspapers are not merely documents, they provide necessary forums for like-minded people to meet and share. But they can also amount to direct action, means of attacking systems of oppression and building the world we want to see. There are countless examples of self-publishing’s transformational political uses in the 130 years since Wells hit the road.

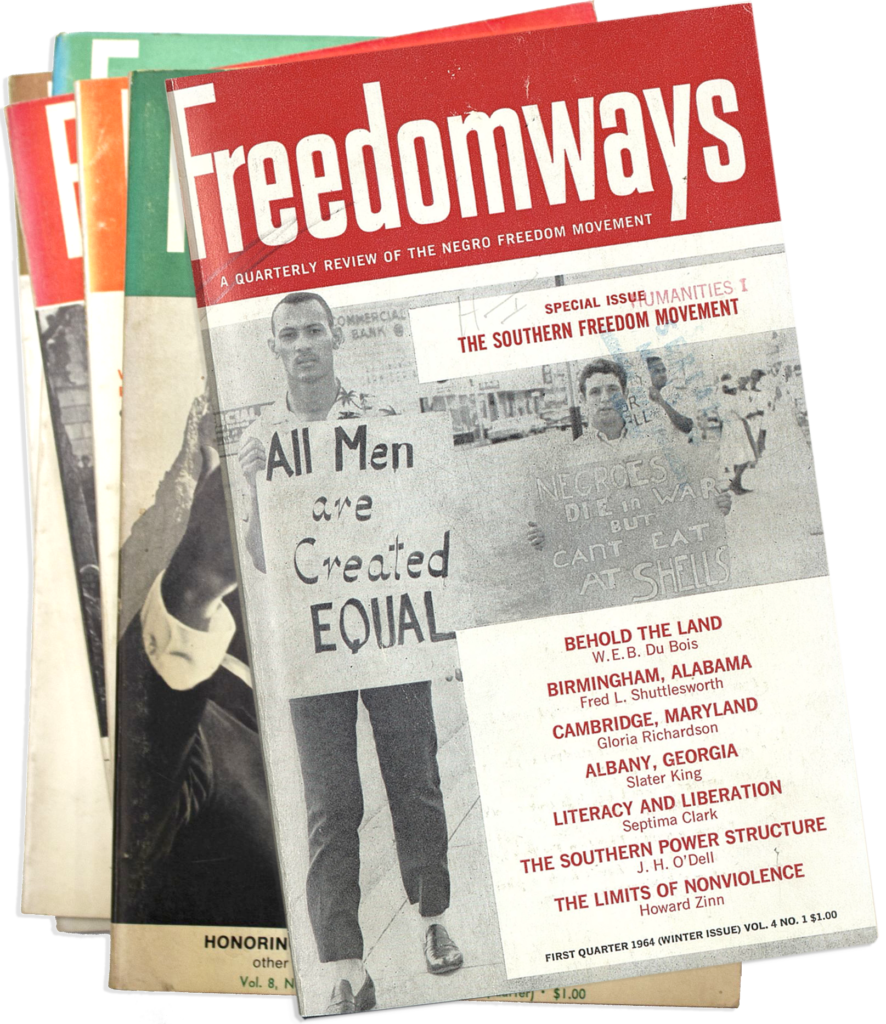

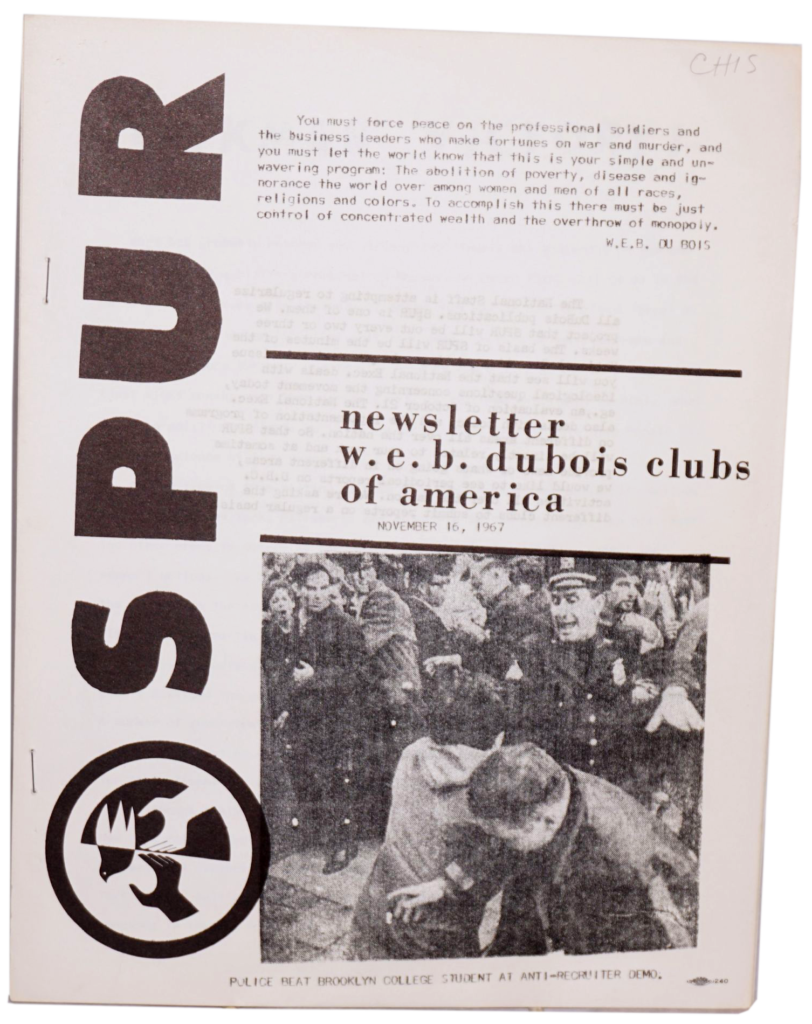

The radical press is integral to the history of Black civil rights and liberation movements, Wells’ pamphlets and earlier publications like the abolitionist weekly The Liberator set the stage for the booming network of newsletters, papers, and journals that formed by the 1950s. The crisis of police brutality was a constant topic of scrutiny. This alone caused the government to view the Black press as a threat. During anti-Communist hearings in 1967, the House Un-American Activities Committee (along with rabid FBI director J. Edgar Hoover) damned both the DuBois Clubs’ Spur newsletter and Freedomways as being “subversive influences in riots, looting and burning.” The Black Panther Party, already a target of mainstream headlines, wasted no time in mounting a counter-narrative. They launched their weekly newspaper only a few months after the party’s founding.

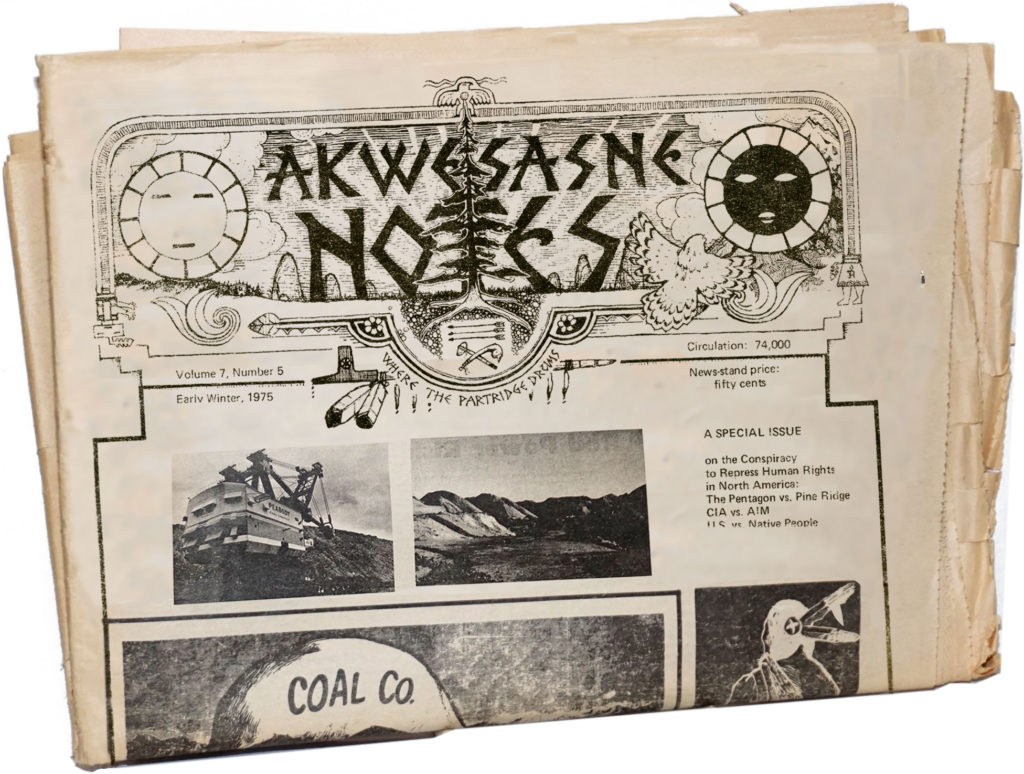

Indigenous nations have used the printed word to expand on unique traditions of knowledge-sharing in political movements. The Mohawk Akwesasne Notes in the late ’60s, Akwe:kon Journal in the ’90s and Salish Sea Sentinel were pages meant to fill the void of fair Indigenous representation in the corporate and state-run newspapers and radio. Now, print publishing is part of 21st century decolonial movements — just look at Treaty 1/Winnipeg-based Red Rising or Atrocities Against Indigenous Canadians by Jenna Rose Sands.

Anti-racist and decolonial movements have, of course, benefited from the diverse forms of political thought held by the people involved. This overlap necessarily meant many intersections with the Left’s more ideologically-driven print traditions, too. Socialists and anarchists have long emphasized the importance of autonomous news, books, zines, and other “counter-info,” a legacy carried forth by the likes of AK Press and distros like Semo, CrimethInc and Sprout. Early gay liberation struggles in Canada positively orbited around The Body Politic and Pink Triangle Press. Radical queer zine publishing continues to thrive today, with more nuanced and intersectional projects at the fore. ’90s movements like riot grrrl and genderqueer were built on zines and punk. Osa Atoe’s Shotgun Seamstress famously challenged the tacit racism in these cultures, pushing the scene to make good on its professed politics. Perzine makers, punk zines and POC distros press on similarly today. Sex workers use zines as safety and organizing tools. Prisoners and prison abolitionists too. So, say it with me now:

You might be thinking about your role in all this. Where you land will be unique to you. Within zine culture, normative whiteness still desperately needs challenging, especially if we are to bust through the walls of our bubble and nourish a growing zine resistance. Black zinesters and independent publishers have known what to do since forever. To you, I say thank you. And of course, real thanks can start with purchasing, reading, sharing, crediting and otherwise supporting Black creators and activists.

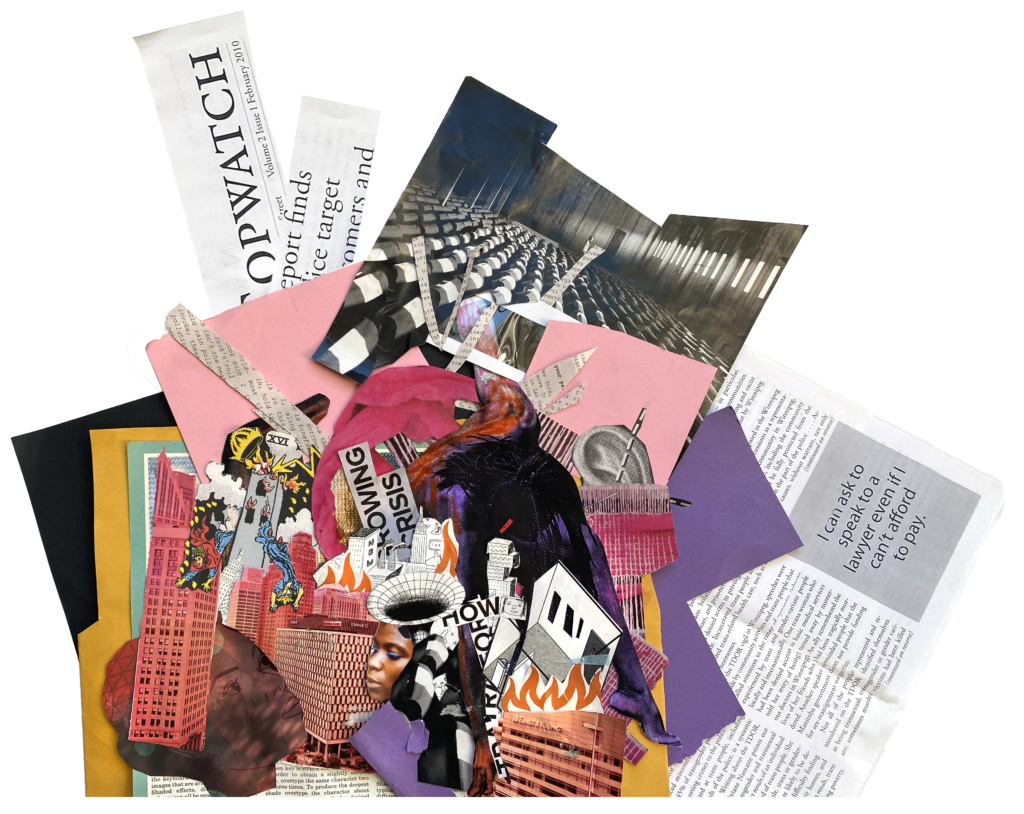

White and non-Black zinesters, build a habit of asking ourselves what we can offer and how to make that known. What skills might your zine-related or printmaking expertise offer to movements wherever you are? Even if you’re not making your own original work in defense of Black lives, you can print someone else’s, distro it and share skills and resources. Brown Recluse Distro, always a beacon of POC zine power, recently secured an ongoing donation of free printing and distribution for Black zinesters. Denver-based Is Press has offered locals free protest signs, custom printed in-house on letterpress. At protests and vigils, folded, pocket-sized sheets with medical, legal, and other information are passed around, defying digital monitoring by law enforcement near and far. New and seasoned zinesters alike are documenting the scenes playing out in their streets, and will continue to.

Not everyone can go to rallies and marches, even with no pandemic. But there are many ways to zine up for racial justice. Wheatpaste the town (or even just your block!) by cover of night. We can still get our zines out via the mail, via friends, or through organizations — what about equipping people in the streets with basic street medic skills or a know-your-rights refresher? If you’re extra sharp with an X-acto, stencil some signs, and hey, see if anyone wants to help and learn some of those zine skills too.

Listen, if anyone can find their way to copiers en masse in the times of COVID-19 and martial law, it’s gonna be us. If anyone can access tried and true anti-racist and activist zines, it’s us. If anyone knows a thing or two about resistance founded in respect for the leadership and experience of people on the margins, we do.

Zinesters, let’s do our thing. We are the radical press.