It was sometime in the late spring, 1994, when I finally wore out my tape of Nevermind. The black plastic case of my Walkman snapped its sharp springs open and closed near continuously. Then the drawn-out slog of muffled distortion as the tape caught under the heads inside. For some time I could pry out the jammed tape and rewind it back through the heads; I couldn’t stop listening to those songs. The dark tones in the treble made my muscles tense, almost ache. The drums, like waves, reached the edge of my skull. When it finally gave in, died as the cassette tape wrinkled like an accordion, I felt this impending sort of storm. A black cloud of inching doom.

Everyone always laughed it off, but I swore we could all sense it. Sam lost a tooth when she moved above Moody Park, up past the library. Her duplex neighbor, whose name sounded Polish though we never got it in full, left a baseball bat on their joined fencing; it leaned wary, half a threat. It gave her a fall that cracked the front right. The Pole shrugged, then brought her mom bitter cabbage soups for a month. Sam loved her teeth too. Begged us all to floss in that crescendo of voice, her mother’s screech. Crystal lost her virginity somewhere under the piers. Complained later of a limp so bad she associated the two; sex and a fucked-up foot, even after she discovered amber glass embedded deep in her callused sole. But she loved bare-foot summers. Trained her feet to grow the thick skin that made her feel closer to the earth. I said it might make better sense if we had forests around, like they did in North Van. Not the half empty storefronts on Columbia. We joked of her hippie tendencies; she laughed and said hippies didn’t work at Orange Julius or live in New West.

I got stabbed walking alone one night, between where the trains hugged the Fraser and the trees got close under the Pattullo. I loved the barges, the silt of the river. The desperate gulls yipped like coyotes as they circled, landed on the tugs. The flash of each white body as it erupted skyward. Before the waterfront became a Waterfront. I was oblivious, focusing on where my feet landed, balancing on the railheads. Tried to space my gait like when I was a kid. I wasn’t sure what I imagined them to be, the ties and rails. It just felt like the thing to do. The pull of my bowlegs arched with the curved out-step of my shoes, black-suede, skater-worn. The screams in my headphones felt good. I thought of leaving town. I always thought of leaving town those days. Head west into the city, or south to Seattle.

I crossed the track, buckled my ankle, landed flat on my palms. The sharp stones poured between the ties cut me. A low brick wall ahead of me shifted. Out merged a ragged figure, startled me as one shape became three, like a weird metamorphous bird. When the men, amorphous in their rags, emptied my wallet, they found nothing but five bucks and a photo of Brady. My throat caught; made an awful sound like the crunch of skate trucks on a nick of stair. The photo was from last summer when Brady and I canoed across Buntzen, the only time we made that trip. We had borrowed his dad’s G20, their old van I loved, a feat of generosity his dad never remembered again. It was the first time I thought—Brady and I are friends now. We smoked Du Maurier’s stolen from his mom. I would laugh when he called me Scoter, the name of some dumb duck his dad hunted on the coast. A hefty sort of bird. We’d seem them once, a raft, Brady called it, all grouped together, and when they finally lit up from the water, it took a few long seconds until they looked like birds, flying. Like you—Brady said—clunky and awkward, until you’re just skating, ignoring everything around you. One of the men called me a fag and the other snatched Brady’s picture, the third had the knife. It grazed me; it caught somewhere in my skin and twisted. The rags didn’t even run, just walked away, kept going west along the tracks. When the nurse told bad jokes, I half-smiled—congrats—she said—you survived and none the worse for wear—though I wasn’t sure what she meant.

Some kids a couple grades below me found a dead bum in the Ravine, near where there’ve been tents since I was a kid, not just since the bums have been pushed from the city. Those kids played tough and cool, but you could tell they were shook. Could see that sway of mortality like a pendulum in their eyes. Some rotted stinky corpse half buried in winter’s release, everything turned to gunk. Flesh just a part of the ruthlessness of another cold winter. Late spring melt, early summer rains; eventually everything’s exposed.

Brady fell in love too. Loved some crazy girl we all met only once or twice. He about disappeared those few months, gave some mumbled impression we should get together and then was never home when I called. We never talked about him, Sam, Crystal, and me—but I must have tried that kid every day or two. I missed our silences, the way we could just lie near the water and listen. Feel summer out. Even though we agreed about the crickets, and how it was so goddamn relaxing to listen to their soft rattle, I like to think we just enjoyed each other’s breathing. That was the relaxing part to me. The real part of summer. The sun on my face. Napping and waking. Brady there, always chewing on some long stiff grass. Sedge, he called it. First time I ever heard that word. He swore he had a preference and I always laughed; I liked his grass theories. When the girl broke his heart, left him for some college jock, Brady still took weeks to call.

When I finally saw him, a couple weeks before the start of school, he was different. I could tell he was distracted. It depressed me. He said he saw her everywhere. Said when the phone rang, he jumped. When a car door slammed, he got sick to his stomach. When his parents had company, he didn’t know why, but he expected her to appear behind some smiling middle-aged couple. He said—Dude, I knew that girl my whole life—and when I would say it had only been since school got, he would reply—Whatever man—and his eyes would fade.

Truth was, I was losing him. I tried to play it cool but mostly I don’t think he thought twice about me. Yet sometimes it was like he looked right into my soul. I’d never really considered that word until Brady. But something fit right, where he’d pause for a moment, looking. His eyes would grow wide and he’d smirk—Hey Scoter, let’s go smoke by the river—and we would, for hours. It was this feeling I got being around him. Like there was a hum that quieted everything.

When I told Crystal, she looked down at her smoothie—Like the world is brighter? —she laughed.

I didn’t expect her to understand, but it stung—Yeah, when I know Brady is around it’s like there’s a fucking glowing hum out there. And when he’s not it’s all just duller. Plainer. Shades of grey and tan, you know?

Crystal didn’t know. She was three months pregnant and not at all pleased. Virgin birth practically, she said. Complained it was eating her inside to out. But the way I saw it, it suited her. Sure, she looked a bit wild: bangs cut blunt and high across her forehead, teased out sides, thrift store cardigans unravelling at the wrists. But there was something sweet about it. She got gentler, softer around the edges. She didn’t even know it was happening, but I saw. She kept her voice down more. Walked slower. Quit smoking, more or less.

Sam’s new fake tooth shone like a Chiclet in her mouth, but at least she smiled now. Brady would call once or twice, and it would trick me. His voice would catch, cut short. And I would get that sinking feeling in my gut, like things were changing quick. I never went back to walk the river bank, and when the train clanged through town, my side throbbed. I wanted to tell Brady, but never did.

We were in those last couple desperate weeks of summer, before the inevitable shuffle back to class. I saw Brady now and then, mostly by chance, as I walked through the neighborhood. I’d join him, like nothing had happened. Sometimes we’d skate over in Surrey, where no neighborhood parents could give us shit. The suburbs were mostly forgotten about back then, before every square of space had something stacked on it. But mostly I never really knew what Brady did. Pretended it was better I wasn’t there, even though it fucking killed me. Maybe I didn’t get him as well as I always thought. I was still stuck in that canoe from last summer, felt the sway of water and the way Brady’s throat looked as he leaned back to let his hair fall, trail in the current. A curl of smoke from his nose.

When I finally heard some kids downtown talking about Brady hitching south to the States, for a moment I thought it was some rumor he had begun. My side pounded. I started this awful sweating. Felt my breath come in short gasps, everything felt close. I thought about the knife from months back, how it had a black plastic handle. It had just been a regular kitchen knife, like the ones I used at home. It had entered my body, skidded along the serrated edge.

It took me months after the stabbing, and a couple more after Brady took off, to realize I didn’t have any other photos of him. It was irrational, but I tore apart my room looking for more. Crystal knew I was sick but didn’t say anything. Just brought the baby over, let her roll on the carpet while we played the same three tapes, quieter ones. Daydream Nation, Siamese Dream, Belly’s Star. She named her daughter Bernadette, after her grandmother. Called her B-Girl for short. I don’t think she even knew what that meant, and I didn’t have the heart to tell her. It hardly mattered. She loved her and was happy. I could see it. She became Crystal’s bright world, her glowing hum.

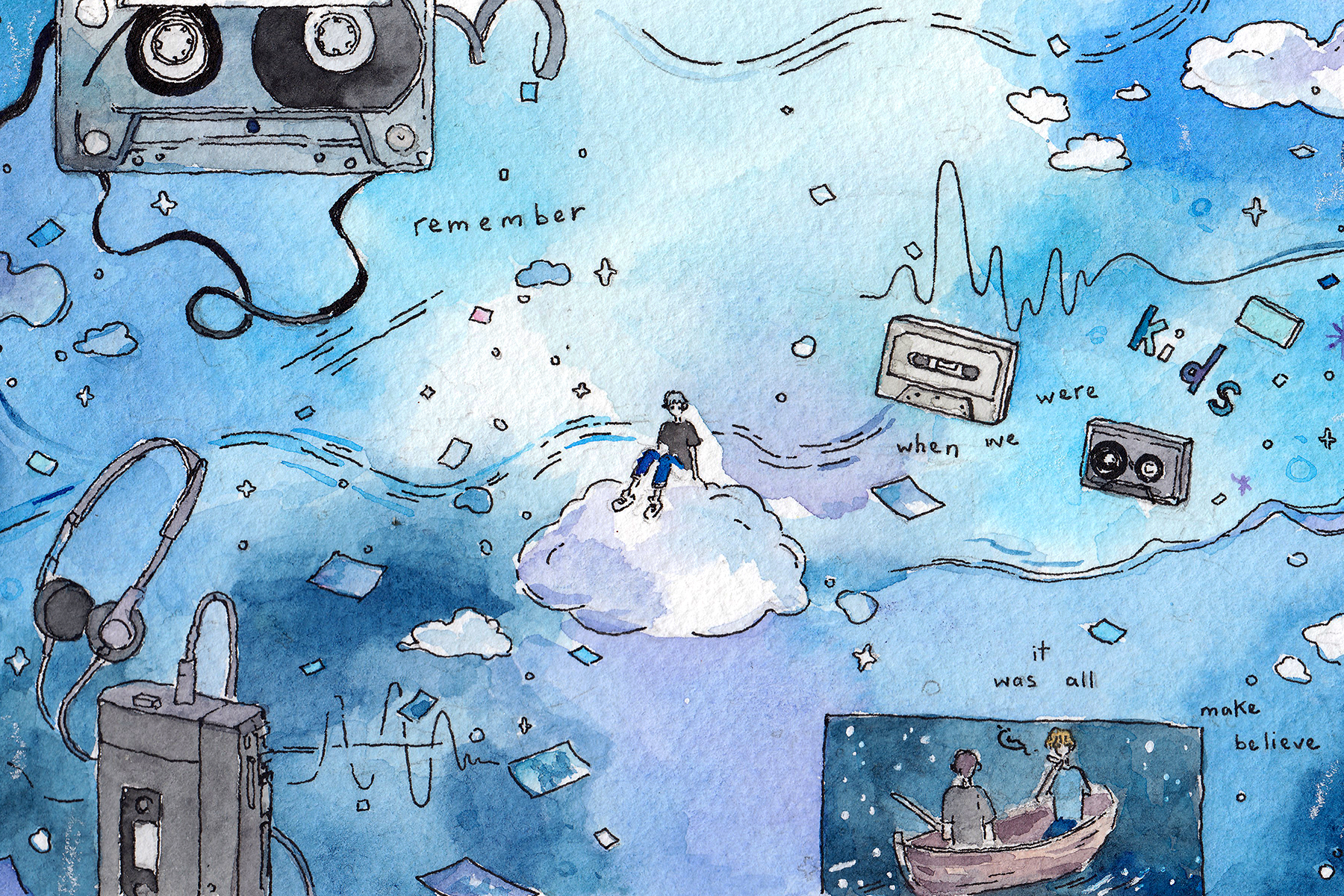

I still think about Brady, near every day. Some days I realize I didn’t think of him, say, the day before, and I get an unsettled feeling. I don’t like less of me to know him; read somewhere your cells are always being replaced. In seven years, you’re born again. Even now, when I’m not young anymore, I see young men like him. Well, not exactly like him. But they might have a stride that’s momentarily his, left foot turned out more than the right. Similar color of wavy hair. Thin long fingers, bony. My imagination, as they say, plays tricks on me. I wonder when Brady hears crickets, he remembers the rock of the water on the bow of the canoe, waves travelling under our feet as we pulled the oars through. Ever sees me through his half-closed eyes as he rests back. Hey Scoter, he would say, want a drag? And his face would lean in, smiling. Remember when we were kids.

It was all make believe.