Before COVID-19, many people only distantly understood the term “mutual aid.” But it was suddenly on everyone’s tongues as we witnessed the pandemic’s first shockwaves into the logistics sector, and the subsequent evaporation of excesses in the global supply chain. In other words, we needed each other in different, more immediate ways. Mutual aid is a framework that directly answers to such immediacy. The term refers to any system of exchange or support between individuals and groups without bureaucracy or state management. In 2020, ad-hoc aid groups sprouted up seemingly overnight, organizing to provide food, protective equipment, shelter, and supplies to their neighbours, who, for their part, pitched in as well.

Of course, sprouts don’t spring from thin air. Here in so-called New Orleans, LA, people on the ground saw precarity coming for ages, without needing to first witness any fist fights over toilet paper at a Costco with a four-hour line-up. An autonomous food production project we agreed to call Lobelia Commons synthesized various mutual aid projects, relationships, and core values that long preceded the present situation.

We start from a shared understanding of place. Long before the arrival of the French, “New Orleans” was known as Bulbancha, a site of exchange, not only economic but also cultural — the name means “the place of many tongues” in Choctaw, a people who put reciprocity at the centre of relationships. Today, a mammoth, 87-kilometer-long stretch of the Mississippi known as the Port of South Louisiana handles around 60% of all US corn, soy, and wheat export. But the kind of trade practiced there now does not honour reciprocity nor responsible interdependence between land, humans, and nonhuman beings. Rather, it deals in extraction and exploitation, relying on a globalized system that fractures communities into no more than consumer units and marketing demographics.

When a society’s logistics are based in greed, they inevitably fail to provide basic resources sustainably or equally. Left unchecked, there are few options left for most of us, given that we have been completely alienated from natural resources. The government’s paltry attempts to prevent mass starvation unravel before they even begin. We are left with each other and a shared place. Collaborative, ground-level projects represent the only path forward to provide for basic needs like crops and food production. This is known as the commons.

What the commons can look like

So what does Lobelia Commons do, practically? It changes every day, guided above all by solidarity, learning, and exchange around food, plants, and people.

First, of course, our members tend to a few neighbourhood gardens around town. Whatever we harvest helps supply an allied mutual aid project that distributes fresh food and other supplies. We take care not to garden without knowing whether neighbourhood people are into it, are already gardening, or can participate in such a project. Some of us also live part or full-time in the country growing food.

A bunch of us collaboratively grow and learn about mushrooms, which are endlessly useful and resilient. Recently a bunch of us inoculated logs together — it’s as fun as it sounds. Mycology surrounds us all.

One of our other initiatives is the decentralized nursery, which merely spotlights and networks the common practice of neighbours sharing plants by leaving extra seedlings in front of their houses. The goal is for people to share plants, but also exchange knowledge and build relationships of mutual support between neighbours. We encourage others to start their own such “micro-nurseries,” so get in touch if you want some tips and we’re happy to help you get started.

In related work, we started a plant seedling delivery service, where we provide free, healthy baby plants for anybody who wants to use them on their windowsills, in gardens, or wherever they like to grow things. This is an excellent way to connect with people around you in a new way, and often you can learn a lot from people once you start talking plants, seeds, and land.

To break down constructs of land use, we recently began a free fruit and nut tree program. The idea is to work within neighbourhoods to make them scattered orchards. We’re planting various trees in publicly accessible spaces and yards, where people can access the delicious food these trees produce. Of course, many places already have fruit-bearing trees in plain sight, though they often go missed. We hope adding to them and mapping them will allow for more and more communities to enjoy fresh fruit and nuts at no cost.

We recognize the inadequacy of our hyper-local projects in seriously addressing widespread hunger. Instead of claiming to solve such a massive problem, we simply promote an approach to food production that centres joy and working together. It is our belief that our sustenance should not only begin to be in our own hands, but also inspire an imaginative participation in the ecologies of these food crops, then these practices will radiate into the building of other capacities for autonomy.

Settler capitalism’s ongoing severance of Black and Indigenous people from the land cannot be reformed or repaired. There can be no dialogue with a culture founded on kidnapping, racist warfare, and the violent extraction of labor from generations of people in service of plantation monoculture. The seeds of that ugly and unsustainable cruelty are plainly evident in our boring, commodified, and semi-toxic modern food system. No more. We must learn from each other, collectively devising and revising our way to a dignified life we can be proud of.

How to start an autonomous food movement

Lobelia Commons is a fairly amorphous group. People’s participation waxes and wanes, and the collective exists in name, but not as any rigid structure. We almost never have meetings. This all happens naturally, and it can allow for bits of chaos and occasional tensions, but also for flexibility and responsiveness. It’s very much a constant work in progress and will remain that way. We are always learning, even though we make mistakes or sometimes overlook something we shouldn’t. Through this process, I’d like to think we’ve identified some guiding lessons in fostering an autonomous food production network, and many of the lessons can apply to any project that wants to build a better world together.

Centre joy

If a project centers joy, it has good reason to reproduce only the conditions that empower its participants. Food autonomy projects are generally easy examples of this. Not only is fresh food so damn good, but freeing yourself from reliance on shitty jobs and grocery stores makes life easier to smile through. Also, when you grow food, you just don’t have to work quite as much.

In that free time you and your crew can grow more plants, learn more things, enjoy a movie, whatever makes you happy. However, not all food projects turn out this way, so putting intention behind joyous resistance can also require really watching for the ways oppressive and competitive structures can try to sneak in and spoil the fun.

Listen to your context

Gardens are popular, and they can be great, but they always exist as part of a fabric of spatial politics in a neighbourhood. When a supposedly blighted lot in a neighbourhood becomes a garden, it often raises property values and thus rent. Depending on who puts them up, the fences gardens may require for successful growing can also act as symbols of racial and class dynamics. Consider alternatives. Is there a different project that could do that would better foster decentralized participation? Who might already be doing work like this, or know lots about growing here? How are you situated in the neighbourhood? Be honest, is this a community garden? It’s okay if the answer is no, just be sincere with the relationships a garden will foster.

Make yourself obsolete

More than anything else, the project of Lobelia is helping make a set of tools. The sooner other people take them, adapt them, and replicate them, the better. As new mutations emerge and grow into better, new practices, let them go from your own hands. They will flourish, foment, and yes, some- times fail. But any activist project that requires gatekeeping will doom itself to isolation and burnout. Make yourself obsolete by making the best possible tool for others.

Plant for where you are

Plant what grows well in your area. The climate, topography, geological history and failed infrastructure of New Orleans does not necessarily make it an ideal place for us to grow some annuals. The sun is really intense in the heat of summer here. We try to grow stuff that’s going to thrive on those hot days to help keep our soil alive like okra, collards, and sissoo spinach. Not that we don’t try to fudge hardiness zones sometimes. We try to ensure that despite the conditions, there will always be plenty of life that will thrive. We get to work less and eat well.

Notice things and tell each other

Some share their garden journal with what has worked and what hasn’t throughout the years. We chat about the bugs we see on leaves — we don’t know the names of all of them, but know which ones spell doom. Through the collective art of noticing, our food production is guided by critical human and non-human communication. Here, the most critical piece of knowledge is, “sow seeds in March.”

Just because you say it is, doesn’t mean it is

I received this criticism recently, and I think about it almost every day. Just because you say a project is different (or inclusive, or radical) doesn’t mean it necessarily is. This can be true of projects with even the best intentions. Your ethics or politics aren’t always visible to others. How can you move in good faith sincerely, probably failing along the way, and avoiding such magical thinking? I don’t have an answer, but this may stick with you the way it did with me.

Re-creating the Farmer’s Almanac

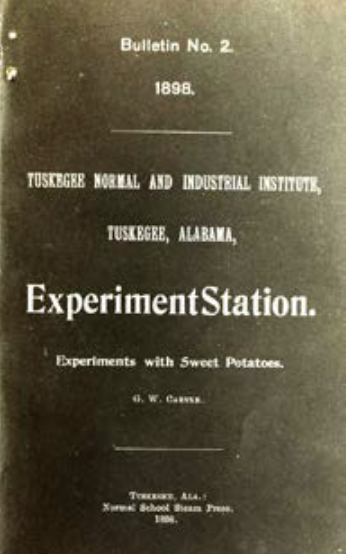

One of our big current projects is putting together The Earthbound Farmer’s Almanac. If you aren’t familiar with The Farmer’s Alamanac, it’s a yearly guide to the year’s weather cycle’s that has been published since 1818. It has fierce devotees and can be useful, but often reads as a bizarre human attempt to stake authority over, of all things, the weather. The idea for our homegrown almanac thus came about as kind of a joke, but we quickly realized it fit with a lot of what we were already interested in doing, particularly in terms of strengthening rural connections. A few of us live in the country and recognize the importance of bridging the urban-rural cultural divide. This is crucial to forming resilient and sustainable communities based on mutual support. I have more faith in analog media than digital when it comes to actually getting to know each other. Printing a sort of alternative Farmers Almanac just made sense. In building it, we led with our values, and took a lot of inspiration from George Washington Carver’s early 20th century periodical, the Experiment Station Bulletin, which was a practical resource that also challenged white supremacist agricultural power.

We also solicited submissions from people we know to be smart, and had an open call online and on flyers. We received a ton of submissions, a lot more than I expected. We’re in the process of doing the layout as I write, and will be printing by April. We aim to distribute copies widely around the Southeast in small rural shops like hardware stores, thrift stores, and barbershops. We’ll let the shop owners keep any sales, which we hope will help us get to know people and get the almanac on shelves at the same time. We’re excited for the possibilities that will come out of this first run and its distribution and aim to produce an even better edition next year.

The almanac and all Lobelia projects rely completely on volunteer labour, and our expenses and printing are being covered out of pocket. If you would like to support the work of Lobelia Commons, or purchase a copy of the Almanac, can get in touch at [email protected] or follow us on Instagram at @lobeliacommons.

Hey Newbie! Get Your Garden On!

Now is the perfect time to get your garden on! Growing your food from seed, like a lot of DIY activities, might seem daunting at first, but once you get going, you’ll realize how rewarding it can be. Broken Pencil’s Cassandra Monk asked three of our favourite gardening zinesters to get some tips for the budding horticulturist.

CM: What would you say to people who’ve never gardened or don’t feel like they have space. How should they get started?

DANIEL MURPHY: Grow something. Anything really. If it doesn’t work out, make some adjustments and try again. Gardening is all about trial and error, and failing doesn’t have to mean it’s not for you.

LAUREN NURSE: There’s no shame in container gardening! Food production is such an important skill and can be practiced anywhere you can find a sunny corner. Five-gallon buckets salvaged from restaurants work great for growing tomatoes, and salad greens don’t need deep containers to thrive, you can grow them in a window box. Food insecurity is a real issue right now and the more folks producing food locally, means the less we need to rely on unsustainable imports.

KATIE HEAGELE: I recommend trying herbs. Many of them do well in containers and will be happy right on the windowsill, and it is very gratifying to grow plants that you can eat or enjoy for their scent. Plant seeds or seedlings (small plants) to grow in pots in your kitchen. Be sure to harvest the plants regularly and cut them back when they get too “leggy.” This keeps them healthy by ensuring new growth, and you can save the cuttings, dry them, and use them later. Hang the cuttings upside down to dry completely, then store them in glass containers away from direct sunlight.

CM: Any hacks for makeshift gardening tools that people could make on the go?

KATIE HAEGELE: Egg cartons are great for starting seeds indoors before transplanting the plants in the garden or to a larger pot. The seeds themselves can of course be harvested from flowers or vegetables you’ve grown or bought at the store. You can also start plants from kitchen cuttings. Try saving the bottom of a leek after you’ve used the part you want to eat and plant its roots in soil. It will grow and you’ll be able to eat it again!

LAUREN NURSE: When we first started farming a decade ago, we had very few tools and we were really broke. Our favourite farm hack was a bent clothes hanger — we shaped it into a makeshift wire weeder and fashioned a very fancy handle for it out of hot pink duct tape. We used it for years until it finally gave up the ghost completely.

CM: Do you have any unique tips or tricks that most newbies would not know about?

LAUREN NURSE: Stale seedbeds — cultivate your beds two weeks before you want to sow something. Let the weeds sprout, lightly cultivate again at the thread stage, sow and you have a nice weed-free bed to grow your plants in.

DANIEL MURPHY: Fill your planting holes with water and let it soak into the soil, then plant. If you were a plant, would you want to be shoved into a dry hole?

Katie Haegele is the co-author of The Kytchyn Witche and author of many zines. Lives in Philadelphia and online at thelalatheory.com.

Lauren Nurse is the co-owner and operator of Small Spade Farm — an experimental, sustainable art farm in Hastings county, Eastern Ontario. Follow @smallspadefarm.

Daniel Murphy runs Awkward Botany blog and Dispersal Stories zine. Boise, ID, USA awkwardbotany.com.