IRL Artists and makers defy the digital dystopia

IRL Artists and makers defy the digital dystopia

In my early 20s, I belonged to an underground queer anarchist cell. We were a campy crew of international saboteurs, squatter punks, and other intense sweethearts committed to direct action and queer liberation.

Obviously this made me feel really cool. What sucked was I couldn’t brag about it. This was in 2012, long before “anarchists” and “Antifa” were popular boogeymen in the media, but it was risky business nonetheless. Too often had sloppy chatter gotten in the way of a squat defense action, or news would come down of infiltration amongst people we knew and trusted. So we took information security seriously. Our rules were simple: speak carefully IRL and encrypt digital communications best you can. Take notes on paper, then destroy it soon after. Before a sensitive meetup or action, we all took the batteries out of our phones and left our devices in disparate freezers (yes, freezers).

It was a rigmarole, but I managed to keep up. And a decade later, securing communications seems endlessly more complicated and certainly more important. Digital surveillance cascades ver all of us, manifesting as CCTV cameras, GPS tracking, and vast databases of information about who we are and where we go. Our emails are as hidden as skywriting. Our resignation to carrying hot microphones in each of our pockets is outdone only by the widespread embrace of a hydra-headed, 24/7 recording device installed in homes everywhere — Alexa. Corporate, government, and Right-wing forces actively use these tools to target individuals and groups, too often with impunity.

Even for less seditious types than myself, the level of scrutiny we all endure can be overwhelming, exacerbating and enhanced by a host of other social violences. Some of us attempt to thwart opaque technologies by adopting our own patchwork of counter-technologies, encrypting and signal-jamming our heads off. We hope it’s all working until, often, we discover it is not. It is exhausting. Our waking hours have never felt less like reality, at least not our own.

Let’s slow down for a sec. Breathe. Think about who you trust and what you know, and I don’t mean code. There must be something we can rescue, rely on even, from whatever we can still feel. I can still picture my old crew, shredding photocopies of handwritten notes that were never uploaded to any cloud in any form. I think back to those cautious face-to-face strategy sessions and skill shares, events that we would never consider marking in a Google Calendar. And I wonder.

What if, instead of doubling down on digital, we invested equally in analog? Or, even better, what if we can use analog media to defy and defend against our would-be watchers, even now?

I’m not suggesting we abandon digital platforms en masse, opting to cling nostalgically to laserdiscs and twee postcards in obscurity (which does sounds fun, in a way). Unplugging ourselves from an unfriendly world is probably futile, certainly selfish and more likely than not an option built on privilege and access to power. And it won’t keep us safe for long, anyway. It won’t repair what’s broken. Rather, I’m asking all practitioners and believers of analog, IRL, and print cultures to begin to view our work as the vanguard of an emerging philosophy, a movement reclaiming interpersonal trust by revising our conception of tech. Some of you are already doing it, you know. Call it: analog liberation in the digital dystopia.

ZINES TO KEEP US SAFE

What qualities of analog can we renew and revise in the pixellated era? Let’s start by looking at our favourite resurgent analog star: the zine. Zines have endless histories, iterations and possibilities — but

they all share a code, of sorts. Once creators release their work into the world, there’s a basic trust that whoever may read it and pass it on will respect the spirit in which it was made. If the work is anonymous, you don’t go looking for the creator. Nor do you resell it for $25 as some kind of art object when it was originally free (yes, this happened to me). And if a zine doesn’t say it’s free for reprint, you don’t scan it in and upload it to your website. But sure, if it says “copyleft,” scam a copier and go off.

Zine culture’s unstated rulebook works, for the most part, because unlike the internet and its tendrils, there’s no middleman. The familiar McLuhanism “the medium is the message” feels apt as an entry point to think about this. Very often, you’re only one or two degrees from the creator of the pages in your hands. You’ve met this person, perhaps, read their thoughts and ideas. There’s a connection, however fleeting. Perhaps this was the original goal of all lasting communication: to cast the net just a bit wider; to reach out to others not directly in your family/tribe/community, and to share your way of seeing things.

Zines, unlike many media, still perform this function. They remain autonomous and independent while, time and time again, various entities have failed to commercialize or control the format. The zine and whoever holds it still touch each other. A zine is potentially far reaching and far travelling, but it is special, one hyperspecific example from infinite variants. A zine is personal, relational, political.

Somehow, zines reach the people they’re meant for. Vulnerability, intimacy, and collective trust form a potent power, whether they land in another hemisphere or stay close to home. Zines made by and for a defined community can have unique political and material impacts

Take bad date lists, a practice that has spread within sex workers’ organizing over the past decade. Sex workers have always shared sensitive information about undesireable clients, how to avoid bad situations and the like. But The Bad Date Book is a concentrated, intentional container for this — a pocket-sized, monthly mini-zine listing recent incidents, safety information and referrals made by and for sex workers. The entries submitted are anonymous, and copies circulate widely, but mostly within the related communities. It would be unlikely for anyone to access these publications without being weren’t looped in already. There isn’t the risk of someone stumbling on it online, nor of sensitive details running loose.

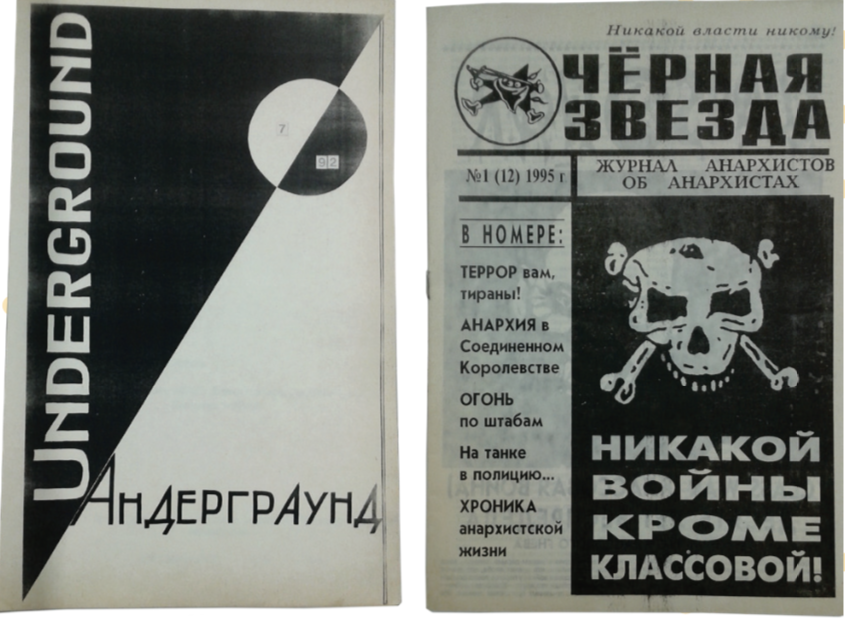

A more historical example might be that of Bez Zhmogas, an early Soviet rock zine that was apparently so threatening to the KGB, an infiltrator was sent to endear himself to the punks who published it. After several months ingratiating himself, the snitch ran off with the master copy of the zine’s second issue, never to be seen again. What did he think he’d find? Zines are powerful, and, in this case, threatening enough that an oppressive state was set on stopping its publication.

The special political potency of zines takes many forms, from historical propaganda machines to zines snuck into prisons (or made inside), to community publishing projects and one-off teenage mini-comics. So of course, I’m inclined to think, shouldn’t we be printing our revolution, keeping ourselves off the grid?

Examples of Soviet-era zines from the collection of Mark Yaffe, founding member of Bez Zhogas. While many of these zines weren’t so much seditious as they were artifects of youth counter-culture, they were at times forcefully repressed by authorities.

SECURE THE PAGE

Like many zinesters, my first love was the photocopier. But what was once a means of bypassing detection has, too, been compromised. For decades, copiers functioned without ever interacting with a network, much less a PDF or hosting server. The hard copies produced were thus, the only copies — their source essentially untraceable.

Few widespread technologies remain truly analog. Most modern copiers produce temporary files, rendering any scan the property of whoever owns the machine. Though these printing files are often short-lived, tech corporations are loath to let user data slide away completely. Their solution to tying the document to its creator? Interestingly, they’re answer is to meet analog with analog.

Meet micro-dots.

An increasing majority of modern laserjet printers use these secret markings to embed metadata. Within each rapid impression, the machine will also hide a pattern of miniscule yellow or white dots invisible to the naked eye, usually in the corners. This secret watermark contains at least some metadata, such as the printer’s serial number and often the time and date the print was made.

This simple form of steganography (the art of hiding messages within messages) has been an increasing standard in laserjet printers for about 15 years, though the technology is much older. In essence, the tracking technique represents a sly gift from megalithic hardware manufacturers, like HP, to their friends: law enforcement. After all, it’s most often the police who actually decode microdots and use the data to prosecute people. Perhaps the most notorious instance of this happened in 2017, when intelligence specialist Reality Winner mailed printed confidential NSA documents to The Intercept to expose new information about Russian interference in US elections. When she was arrested for the leak, many theorized that authorities identified her thanks to the dots on the scanned image that the news site published unedited. She remains in federal prison. In the wake of this whole affair, the badass digital watchdogs Electronic Frontier Foundation did an investigation. They crowdsourced print jobs from thousands of Kinko’s branches to compare dots, cracked the code within, and published a decoder for anyone wishing to know what metadata might be hidden in their meeting agenda print-outs. What’s become clear is that there is no easy way to block the dots if your printer, like post, has such a feature. And don’t ask too much about it — in the earliest years of dot tracking in printers, a customer called a manufacturer to ask how to disable the function. This resulted in a personal visit from the Secret Service. Suffice it to say, don’t throw away that shredder in your closet.

But how and why do these state and corporate regimes converge on the page just so? It’s not to send hidden messages. Rather, the goal is to make documents dense enough that they can secure and enforce power and capital. Think banknotes, passports, and all of their intricacies — these are legitimized through the secrecy and complexity of their production. Print media, and its unique authenticity, is actually key for those in power to control huge categories such as currency and identity. Isn’t that something that, however opposite in positioning, us zinesters know deeply? Those of us building intimate distribution networks for handcrafted info zines, or otherwise choosing analog to beat back digital despair, know a thing or two about printing our way towards inimitable trust. Long the domain of militaries and corporations, might we find new insights and inspiration in so-called security printing?

Examples of modified Occupy George bills circa 2011. From occupygeorge.com

(DON’T) COPY THAT: SECURITY PRINTING

“If you’re in security printing, then be in security printing.”

Stoic, Dick Warner was appropriately cautious about details as he spoke to me from his home outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warner’s remarkable career fighting large-scale counterfeit operations of American currency has made him an expert in the field of security printing. These days, he is a consultant for private and public entities wishing to produce banknotes and identification documents impossible to reproduce. But, lucky for him, I wasn’t so interested in the secrets of the mint, myself. Instead, I wanted his thoughts on the promises and pitfalls of both analog and digital processes when it comes to securing a paper document. To him, the winner is clear.

“Digital is competitive, no doubt about it,” Warner concedes. “But you can do an awful lot of things on that analog press, whereas with digital … you’re not as able to screw around with it.”

Traditional processes like intaglio, letterpress and offset printing remain the standard, Warner says — all three are still used everyday to print American and Canadian currency and passports. Warner explains how the uses of single pigment inks, and particularly the practice of splitting ink fountains, is just one irreplaceable analog technique meant to foil would-be counterfeiters. Splitting enables ink colours to mingle seamlessly on the press plates, creating rich continuous tones that a scan-and-print imitation can’t achieve. Even advanced counterfeiters who print with the same traditional machines will struggle to decipher the makeup and sequence of plates when many layers and colours are combined.

As our talk veered into the technical aspects of printing methods, I found myself wondering how these mechanics might be useful in various other contexts. I can easily imagine possible uses of secure and inimitable printing within activist movements — perhaps internally to detect infiltration, but also as a way of understanding print’s role

in security culture more globally. While my own idea of a social utopia might not involve banknotes at all, the revolution might still need passports, right? After all, they do kind of look like zines.

Warner, of course, is a government security expert and expressed little interest in the uses of print for political movements, artists, and the like. But he certainly confirmed that these practices he’s refined are powerful on a global stage. He pointed out that, contrary to the assumption that counterfeiters are in it for a personal cash out (certainly a secondary benefit), these large scale operations are just as likely to be used in the name of geopolitical upset. Warner himself spent many years combatting one specific printing outfit that they finally located, along with $8 billion-worth of fakes, in a remote cave in Iraq.

“If it’s not for money, maybe it’s for a power play by one country looking to discredit the economy of another country,” Warner shares towards the end of our conversation.

“It depends what the goal is.”

The fact is, Warner says, sometimes it works, and mastery of the press and the right machinery goes a long way.

“It depends on how much you want to put into it,” says Warner, referring to people aspiring to print securely and those who would aspire to fake it. “It’s a commitment, but if you’re willing to really do it, it can be done … And you’re going to end up in the analog world at this point in time,” he explains, saying he doesn’t see digital taking the lead for a long while.

Perhaps us analog enthusiasts should give ourselves a little more credit. If we’re willing to learn, the printing protocols that run the world aren’t so far away. What might we get from these techniques? Why not try? Now I’m not condoning counterfeiting here, far from it. I’m merely saying that these tools are major — and we can learn them, get creative, and open up some pretty radical new options.

“Digital is competitive… But you can do an awful lot of things on that analog press, whereas with digital … you’re not as able to screw around with it.”

THE ART OF COUNTER-SURVEILLANCE

Wait — what happened to lo-fi and DIY? Rare is the zinester who has the money to buy megalithic offset machines, it’s true, much less an interest in ID card design.

Back in 2011, artist Ivan Cash found a much simpler way to harness the unstoppable momentum of global cash exchange — not by printing his own dollar, but by printing on the dollar. Building on the momentum of the Occupy Wall Street movement, Cash and his collaborators got international attention for a project called Occupy George. They designed five rectangular stamps that, when inked onto the face of a one-dollar bill, overlays infographics right onto the bill itself (perfectly legal, it turns out.) As a result, striking facts about economic disparity reached the hands of, well, anyone who lucked upon the right single. The infographics in and of themselves weren’t unique for the moment. But the vehicle certainly was. The medium sure is the message.

Cash has since enjoyed a lucrative career as a corporate artist and low-key ad man, and feel good analog is his trademark — think group letter writing, temporary no-tech zones, and strangers drawing each others’ portraits. Revently, Cash crowdfunded the production of IRL Glasses, some stylish frames that block out any screens caught in its sight lines. And they actually work. Unsurprisingly, the shades were quick to, you know, sell out. But not all of us are spunky brand strategists like Cash. Worry not — there is so much artists can offer.

IN PATTERNS

“Every person who’s used to working in art, printmaking, or patterns has all the skills at their disposal to play with these systems,” says Kate Bertash, a digital security specialist and multimedia artist based in Los Angeles. These supposedly all-powerful and impossibly complex surveillance technologies aren’t actually that smart, Bertash explains. That’s mostly just a marketing ploy to sell them to police, and freak out the media and the public. In truth, a lot of these systems are dumb. For curious, tinkering, creative minds, that could be an opportunity.

“The real world is a lot more complicated than computers can currently handle,” she explains. “If you can weaponize that complexity and add some of your own back into it, it’s more powerful than you would think.”

By day, Bertash does digital security work for abortion access organizations. But her various other projects span many fields, driven by a willingness to creatively experiment and reveal cracks in the system. Artist’s intuition, it turns out, can get you pretty far.

Take her recent line of apparel, Adversarial Fashion, which messes with Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) databases. An ALPR is a creepily common tool for anti-abortion vigilantes, but also a favored form of tracking data of the police. Last year, during a casual conversation on the topic, a colleague of Bertash mentioned that the cameras frequently misread things, registering things like billboards and fences by accident. A light bulb went off — what else might an ALPR misread? A lot, it turns out. After amassing piles of images, mostly of license plates, Bertash edited them into tons of versions with different qualities and distortions.

“I built up a huge pile of plates and things and basically it was just like using it to test my own hunches about how I think the system works.” Bertash explains.

She uploaded these different versions to an ALPR software to see which characteristics were dependable triggers. When a few consistencies emerged, she designed seamless textile patterns with the same qualities, embedding the triggers into apparel. Adversarial Fashion offers all sorts of clothes and accessories with such patterns. These trigger ALPRs whenever people rock them in the wild, thereby adding junk into an already fragile data set, rendering it even less reliable for those who would exploit it. Bertash’s trust-your-gut tinkering is what early hacker-verse

thinkers would call an “adversarial black box method” — early hacker- speak for when you interfere with a system or mechanism even though you don’t quite know what’s under its hood. Tellingly, a 21st century take on the method must pass through the real world to succeed. This is the arena for artists to thrive, a threshold space between the cloud and the ground. With algorithms, cameras, chips, GPS devices, and microphones virtually everywhere. There are endless opportunities for creative minds to observe and find ways to intervene.

“Those are the critical tools that help artists in particular to ask questions and gut check what [you’re] looking at,” she reflects, speaking about the inclination to observe and test things; “or just putting samples in and seeing what your artist’s intuition tells you might be happening, and then chasing that curiosity.”

This may just be the art we need. As technotronic as it may all sound, we’re talking about listening to our senses in the real world and recognizing that they are infinitely more effective than those of machines. While there is a huge body of contemporary art commenting on the perils of surveillance culture, these works are frequently theoretical, reflective, and full of fear; Bertash’s action art approach distinguishes her as belonging to a small but growing group who, instead, view art as a plane of practical intervention for resistance. Some are artists, others activists, and some are just, you know, people.

Perhaps the most celebrated project in this vein is known as CV Dazzle. Developed by artist Adam Harvey around 2010, this anti-surveillance camouflage technique uses high-contrast make-up, colour blocks and adornments to confuse facial detection software. The results are striking visages invoking cubism, drag shows, and posthumanism all at once. During the sustained protests of 2020, the method caught another wave of viral popularity, but it didn’t take long for Harvey himself to burst people’s bubble with a single tweet back in June:

“People emailing about CV Dazzle: you can just wear a mask now. It’s much easier. Original CV Dazzle designs are from 2010, were designed for the Viola-Jones algorithms. It has since been deprecated. But, facial accessories are always good. The more outlandish the better.”

The tech Twitterati, ever anxious to be the first to burst your bubble, lodged onto the first part of Harvey’s tweet, largely ignoring the second. While turnover in specific technologies is real, Bertash takes issue with the eagerness to write off innovations like CV Dazzle.

“I get annoyed with people who are so quick to be like, okay, it’s over, there’s no point in meddling with it,” she explains, saying that doubt do a lot of damage if you let it. While CV Dazzle may no longer succeed in evading facial detection, she points out, Harvey himself suggests that disruptive face decorations can still fool facial recognition, a distinction worth noting.

Bertash’s projects are one of many that continue to play with and understand the artificial neural networks that surveillance systems employ, with relative success. She points to Drag Vs AI, a new workshop series by the Algorithmic Justice League, as another example of how play and pizzazz can be the motor for people to find cracks in the system. This workshop, led by drag and gender performers, invites participants to use the subculture’s tricks and tools to undermine the racist and sexist assumptions built into things like Amazon’s proprietary Rekognition system. Even if these cease to work in a specific situation, Bertash points out, things like CV Dazzle and adversarial drag can encourage many thousands to think more critically about how facial recognition works — and who it affects.

HAPTIC TACTICS IN A CARCERAL STATE

Privacy-eroding technology, built cheerfully by the profiteering corporate sector and used in the justice system to catch and convict, is not just an attempt at monopolizing information. Today’s mechanisms of control are what scholar and activist Sarah Hamid calls “carceral technologies,” where the very architecture of these systems is suffused with the oppressive modes of the powers who pay to have them built.

Devices ambiently, actively tag, track and target racialized, poor, and other communities to mark them as trouble. Black Americans are not only subjected to direct surveillance more frequently and earlier in life than everyone else, they are also more likely to be impacted by the racist effects of environmental surveillance at large. Take the unreliable face matching of the massive Clearview AI database, which scrapes images from the web and social media. This tool is popular with police departments. It is also notoriously bad at telling non-white people apart. The effect is that Clearview-generated “evidence” is used to falsely identify suspects, and thus justify harassing and surveying racialized people almost in perpetuity. Across the continent, so-called predictive policing programs are already reigning local police forces upon innocent individuals and families, purely for being poor, Black, a migrant, a drug user — they’ll use any excuse. Thus an old, old story takes a new form: people in certain geographies or social status are pre-emptively criminalized, forced to engage with the justice system without cause, but certainly causing immediate material and personal distress and pinning them with a record.

Artistic resistance tactics have no problem scaling up to meet the challenge, though. Anti-racist and anti-fascist protest movements around the world keep showing us how effective a simple, creative twist can be. For instance, recall the light show flashed around the world when Hong Kong protestors swung laser pointers simultaneously, a spectacle that not only inspired street demonstrators everywhere, but compromised police cameras and thus their ability to identify and apprehend people who, at the time, had also taken to pulling down high tech lampposts outfitted with cameras and microphones.

Meanwhile, across the U.S. and Canada, protestors took charge and dismounted, destroyed and disfigured statues, and other public tributes to white supremacy with a collaborative, performative pizzazz. In the same way that jamming up a Google traffic system is as intuitive as can be (walk thirty phones across a bridge with Google maps turned on and by the end, it will be predicting major delays), so too are the IRL innovations of protestors in Portland and elsewhere — beat back teargas with leaf blowers, why not? Achieve large-scale vandalism in a fraction of the time by converting expired fire extinguisher canisters into massive spray paint devices? Well, we can’t legally recommend it…

I could go on and on. That might be part of the difficulty, in fact. We’re faced with a conundrum of scope, scale, and direction. I see many political movements just shy of consummating an important symbiosis. In my eyes, meaningful, grassroots organizing is irreplaceable in the fight for social change. Clever design and social innovation will never be enoch on its own for social change. But individual artists and their clever ideas and projects have the potential to at last start important conversations, and, I’d advocate, to be taken and tested in the streets at a bigger scale. Collective action and mass protest are strengthened by curious minds and the tools they produce. Mass adoption of security measures must go beyond the requisite photo-scrubbing and Signal messages and become real tools you can feel — haptic tactics, if you will.

A familiar tune of doubt and despair starts to play behind every little conversation about the state of things, as though “they” have won, with their big cameras and computers. But recent history tells us that courage rather than doubt serves us. If we muster the same impulse that is bringing so many masked faces into the streets despite so many risks, we can see how large-scale adoption of adversarial techniques in the living, analog world can foil our foes.

We stand to harness an immense power. I can see it, really. Anti-racist activist spaces with walls layered in anti-surveillance, and lots of typewriters inside. Militant labour unions offering pen and paper cryptography training to workers. Reams of fabric with fashionable patterns that, unleashed en masse into the world, will leave Big Brother reeling and confused long enough for its wearers to sneak through to the other side. All hail analog, into glory ride — never alone, always side by side.

WHOSE SIGNS? OUR SIGNS!

The folks at Black Powder Press recently shared some advice for engaging your local streetscape using electronic traffic signs! Follow their simple steps for improving these ubiquitous signs, and their messages (as a thought experiment only, of course).

1. Many electronic road signs’ access panels are unlocked, or secured by only a tiny lock.

2. The menu on ADDCO signs (a common brand) has a simple option called “Instant Text” — just type in your new, improved message and hit [ENTER] to submit! Canadian Ver-Mac consoles are similarly intuitive.

3. Need a password? Try the preset “DOTS” which no one probably bothered to change. Or, just reset to the defaults by holding down [CTRL] and [SHIFT] while typing “DIPY”, and “DOTS” should become the password again! Easy!

For more details and tips, check out @blackpowderpress on Instagram