As part of our ongoing Global Zines series, we recently interviewed Girdap Zack Unthatow, along with Efe Tusder and Egemen Aykin, of the Izmir, Turkey-based publishing and archive project Izmiryer6 Distro.

What is Izmiryer6 Distro?

Izmiryer6 Distro is an independent art collective made up of many smaller projects using various disciplines, including events, activism, and print publishing and distribution. The distro was started in 2000 with the aim of releasing our original work as fanzines. Our primary mission remains the free distribution of our projects without censorship and independent from any mainstream publishing companies. We also reprint from our archive of work by others with a similar worldview, such as zines and posters to video and cassettes that we do our best to keep in circulation. We also organize events for the public such as zine exhibitions and festivals, talks, performances, and radio broadcasts. The ideal at the heart of our 20 years of publishing is to provide convenience and support to people who don’t want the state or publishing institutions to intervene in their work. We do so without any financial interest, as part of our commitment to action on the streets and the struggle for existence.

How did this project begin and grow?

I’ve been archiving different kinds of materials since 1996 and was aiming to publish and distribute. I had started a website called Street Literature in 2001, when the internet and especially social media had stopped being so dominant for organizing. Around 2002, I started the first experimental zine printed in Turkey, Psycho Race. It was a mix of graffiti and street art as well as coverage of the underground rap and punk scene, and we started to share it with people. Face-to-face contact and communication on the street should always be the priority, and we met like-minded people at events. So we kept putting out fanzines and reaching out to people to reprint things. Of course, there are sometimes difficulties for ongoing projects, especially if you have no solidarity and collaboration. But we are still here, and this is because we set up stands on the street and built real life contacts rather than trying to be heard online. Solucan, a zine based in Kadıköy, [a neighbourhood in Istanbul], has been around for years and has been especially supportive. They’re known for publishing books without labels or ISBNs.

Can you tell me about the zine culture in Izmir, and in Turkey more broadly? Who makes and reads zines, and where?

The first photocopied publications came out of Turkey in May 1999. Our friends Caglan Tekil (rest in peace) and Esat Cavit Basak each put out the inaugural issues of their zines Laneth and Mondo Trasho, despite being unaware of each other at that point. Soon, lots of people were supporting them and sending in content. Following those seminal fanzines, zine culture took root in the 90s. Zine stands were regular features at punk and metal concerts throughout the 90s but there were also some zines of literature, philosophy, LGBT, art, comics, photography, everything.

Of course, digital publishing became more attractive in the 2000s and many zines became e-zines once and for all, and many people published on their own webpages instead. But in the aftermath of the horrific and violent crackdown on the Gezi Park protests in 2013, people were politicized and underground media spread widely again. We should say that the Turkish government has a totalitarian orientation. There is serious repression and censorship that even puts some journalists and artists in prison. Mainstream magazines won’t give much space to experimental or political content, of course. So a lot of writers or artists choose to make fanzines themselves.

Zine racks are mainly found in bars and cafes in Turkey, and a few of our friends still open stands at concerts. For three or four years now, there has been a real surge in literary zines, fiction, and poetry. Unfortunately this correlates with a decrease in fanzines focused on visual work, but some artists and publishers do carry on.

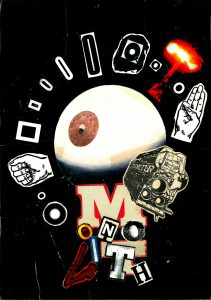

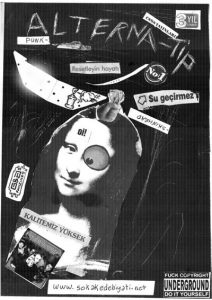

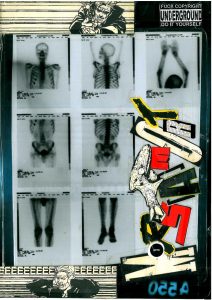

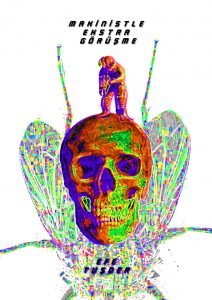

Within our distro, for instance, is Etrafi. He produces 6pilli, a hip hop fanzine bursting with bright original collages and graffiti. Another collective member, Efe Tuşder, makes many weird art and bizarro fiction zines such as Morsamort, which is typed in morse code and illustrated with x-ray negatives of his dead grandfather’s body. He also makes an experimental audio-zine called Extra conversation with the machinist and Monolith, a collage-and-fiction hybrid. And of course, I have been opening zine stands around the streets of Izmir for 20 years and will continue to bring people work by our collaborators and allies, many from other countries. Outside of our distro, mythology-themed Cosmic Zion is more visual. Some other recent solid-good zines right now are Taxidermia, Kaburga megazine, Lopcuk, Dog juice, and Sanrı.

What are other zine subcultures like in Turkey (comics, art publishing, personal zines, etc.) and how do they relate to each other?

Apart from literary content, the production of experimental, music and other subculture fanzines has decreased. Our scene is small but tight. Everyone knows everyone’s name, and friends from different cities can easily find each other at concerts and events. We’ve been organizing a yearly zine gathering in Ankara and Istanbul since 2009 too, where we’ve built lasting friendships and collaboration.

Personally we have a concern with how everything evolves into the internet or social media now and discourses and protests now gradually become only digital, even DIY things like street art, graffiti, and fanzines. It’s more effective and accurate for me to paint on a street wall than in pixels. We’ve built some positive solidarity in the past two years and it’s important we keep up efforts to make connections outside of the virtual world.

Given the political situations, repression, and censorship must be really complex issues… What challenges does your project face?

We print everything ourselves without permission from any official institution. But we also don’t appeal to a very large audience, so we haven’t gotten really serious problems in that sense. We do have some conflicts with the police because we distribute our zines right on the street. They’ve even seized all our stuff and then given us fines. This is happening more often because when we set up our stand, we also play music freely and share the drinks we’ve brought, while they want us to be invisible. Many independent creators and publishers who do appeal to a wider audience than us can face much more intense censorship and repression, even incarceration.

We’ve also had a few problems figuring out how to stay present on the level of street activism, but our biggest challenge is sustaining our business financially. Keeping up printing can be a challenge. However, we’ve overcome this by sending our zines as PDF versions to others who can print them or, if all else fails, read them on a screen.

How can people support your work, contact you, and find out more?

We don’t have a website at the moment, though we are soon reactivating our e-zine and in the meantime we share some zine covers and excerpts on social media. The greatest support would be if readers shared our short introduction text on unpz.blogspot.com (in English and French) with the people around them. But we can always collaborate, too. We’re happy to send PDF versions of the zines in our catalogue, and if any readers want to print and distribute our publications wherever they are, they should do it — no need to ask permission. Our philosophy is, “Do it yourself.”

We want to organize the international fanzine festival, which we have organized periodically since 2013 — in Izmir in the summer of 2021. As a result of the virus and quarantine bans, we postponed our plan for a year. We would be happy to spend a few days with tents and camp music in an area in Izmir, Dikili.

Find accounts for the distro and its members on Instagram and other social media: @izmiryer6distro, @unthatow, and @efetusder. Reach out if you want to work together, we’re down to print and distribute foreign zines in Turkey. Let’s always find ways to act in solidarity. Peace, love, révolte.

Find accounts for the distro and its members on Instagram and other social media: @izmiryer6distro, @unthatow, and @efetusder. Reach out if you want to work together, we’re down to print and distribute foreign zines in Turkey. Let’s always find ways to act in solidarity. Peace, love, révolte.