One thing to know about me is I can make my body disappear. I know how to become invisible, weightless, silent in a threatening world.

More than 300 years ago, Nanny of the Maroons had this same power. The 18th century Jamaican liberator and her militia of former slaves waged war on the British for many years to defend their settlement. The colonial forces were bigger and supposedly better-armed than the guerilla Maroons. But Queen Nanny trained her troops to become masters of camouflage, able to achieve total stealth, blending their bodies into treetops and slowing their breathing so as to be inaudible. After suffering brutal losses for a decade, the colonial forces relented and signed a treaty respecting the Maroons’ autonomy and self-determination.

We still our pulses, limit our electrodermal activity, enter a state of dissipation.

I have been forced to develop a number of somatic techniques to survive inhumane circumstances. I am able to suppress my sympathetic nervous system enough to withstand an juvenile court hearing, an assault, a long 24 hours under suicide watch, a panic attack, a nightmarish adolescence.

A pandemic.

I’ve dreamed of many pandemics, and lived through countless somatic horrors exacerbated by monstrous Western systems. Childhood visits to see my mother in psychiatric hospitals, my own inpatient stays as an adult, various jobs in shelters and other institutions, and my own practice of body-centered sci-fi.

For myself and many other survivors of invasive medical procedures and institutions, or who live with chronic illness or disability, COVID-19 has rustled up heinous memories and fears — being in “lockdown” was enough to give me full-force flashbacks of suicide watch and supervised toileting.

But for able-bodied and neurotypical people, now is a rare moment where they may understand a bit of what we already know about the violence of medical apartheid and neglect.

I’ve spent a lot of this time in a dissociated but functioning state. As someone with psychiatric disabilities and institutional trauma, this state is an essential adaptation. For me, life feels like a delicate balance of the optimal neurochemicals, pharmaceutical dosing, dissociation and distraction, negotiating and triaging inputs and outputs of information and propaganda. Co-regulating nervous systems with my loved ones, watching each others’ faces, mirroring and amplifying the bits of joy we can spark in the midst of this thing. And I maintain this way.

FOR WESTERN SCIENTISTS, THE IDEAL BLACKBODY ABSORBS EVERYTHING THAT SHINES ON IT, REFLECTING OF NOTHING, REMAINING THE BLACKEST, SEEMINGLY UNCHANGED, INVISIBLE.

—Ras Cutlass, ‘A Young Thug Confronts His Own Future,’ Style of Attack Report

And, like any futurist, I look to science fiction, emerging tech, and other speculation for comfort and to ground my actions in my community. Dystopian realities like the one we find ourselves in today require speculative solutions, after all.

This grounds my work as a long-time mental health worker with lived experience of neurodiversity and recovery. Working in healthcare systems firsthand, I know the limits of the U.S. healthcare and social service systems during typical times, much less our current crisis. Sci-fi and frameworks of thought like Afrofuturism, along with disability and racial justice movements guide me and my comrade’s justice work locally. But they also challenge me to see my own body as something beyond pathology, and an instrument of radical imagination.

How many other ways have Black people, people with disabilities, and other bodies deemed undesirable or undeserving, had to discipline, hide, and shape-shift their bodies to survive?

My ancestors developed the ability to perceive embodiment differently, the ability to cope with the sudden surreal time travel created through massive historical violence, both collective and individual.

The ability to wait, to work, to resist, to laugh in the face of ever-present death and dehumanization. And so I wondered, is this bodyhacking?

#transhumanism

“Body hacking” is the practice of modifying your body outside of mainstream medicine or sanctioned science. Its ethos insists that seemingly lofty aspirations are achievable: that citizen science and DIY body modification can produce a utopian reality that — at face value — realizes true bodily autonomy and the democratization of biology, medical research and technological experimentation.

Bodyhacking and biohacking began in the early days of hacker culture in the late ’80s. At the time, libertarian coders and citizen scientists alike cherished the radically democratic potential of computing above all. The poetics of this played out in science fiction in the dystopian subgenre of cyberpunk, in which near-future failures of the social order are survived by cyborgs and radicals, repurposing the corporate cybernetics of their oppressors to resist.

Simultaneously, the body modification subculture of the ’90s and ’00s promised profound ownership of one’s body and free access to technologies to optimize it — implants, chemicals, extensions and more. The underlying philosophy is transhumanism: the idea that the human body is itself a frontier to be conquered and transcended, a tool requiring perpetual enhancement until humankind achieves freedom from the organic limits of the body — as, of course, we must rightly deserve.

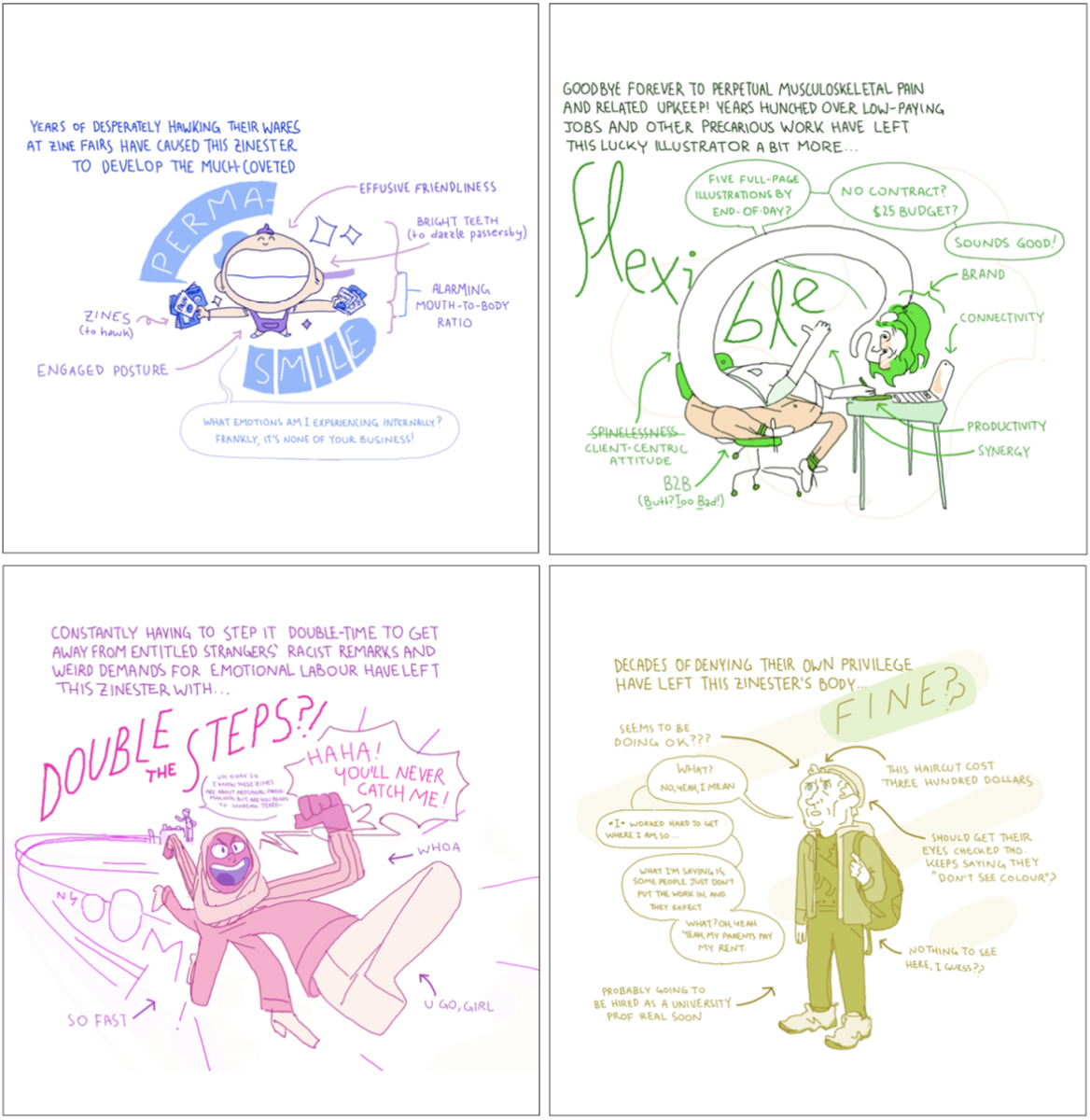

Now in 2020, bodyhacking remains an intriguing thread in our culture around the future of health and care. We can witness the practice and ethos evolving into reality. However, in the age of #lifehacks, home genetic testing kits, and Silicon Valley-fueled quests for immortality, the bodyhacking in mainstream narratives gives off major corporatized, Ubermensch-type vibes.

Any movement with a history and increasing visibility will have identity crises and face co-optation, but the increasing commodification of individualized tech feels far from the anti-corporate ideals of hacker culture and the body mod scene.

“Bodyhacking is inherently queer and punk,” says Tamara Santibañez, a new media artist and tattoo doula whose body modification practice explores ritual and technology. She notes how recently, biohacking’s focus has become “to test the limitations of what your body is capable of, which in a way can be in service to capitalism.”

Indeed, many citizen scientists, disability and trans activists — like those who organize the Please Try This At Home conference, or scientists who work on the Open Insulin Project — are exploring how citizen biology can help us move beyond the failures of Western medicine. But big money has its sights on bodily technologies, preferring to spotlight corporate biohacking endeavours and hide those that defy exploitation and commodification.

Take Josiah Zayner, star of the Netflix biohacking docu-series Unnatural Selection. Zayner gained notoriety for selling home DNA hacking kits and being charged for practicing medicine without a license. Watch the show and you’ll see that Zayner, an anti-intellectual is framed as a lone wolf stunt hero, disconnected from marginalized communities and their activism. Instead, he injects himself with the groundbreaking gene-editing technology CRISPR on TV and tweaks yeast genomes with jellyfish proteins as a way to produce glowing beer. Who does this really serve?

The Black body question

Here in Philadelphia, the spirit of Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, a Black trans woman who was recently murdered, is a constant presence. During a march in her memory and the memory of other Black women and femmes slain at the hands of state and gender-based violence, I witnessed a collapse in time. The street we walked down together was the same one police had filled with militarized vehicles and tear gas just three weeks ago, during another march. The neighbourhood we walked through was the same one the mayor dropped a bomb on in 1985. The feelings of powerlessness and vulnerability, and the traumatic memories of health and scarcity this pandemic has produced in me since the beginning, are nothing compared to the daze I have found myself in during the latest uprisings calling for an end to anti-Black violence.

And I’ve been reminded yet again that Western ideologies, symbols, and philosophies like transhumanism, Xenofeminism and even the basic constructions of reality like ‘science’ and ‘body’ really don’t hold up to my reality, or the reality of the people in my community.

What does transhumanism mean to a being who is not considered human by the institutions they’re at the mercy of or within the society they reside? What does it mean to bodyhack in a time when Black bodies are constantly threatened, sterilized, lynched, drugged, confined, and ultimately disposed of?

Or when Black women and femmes and queer people are chronically forgotten even by their own communities in the nightmares that they endure?

When Black people living with disabilities are finding ways to survive and fight back in their bodies without access to microchips or genetics kits?

Ancestral technologies

I wanted to ask some of the futurists I work with about their thoughts on bodyhacking now and over centuries of dehumanization. One such person is M Téllez, a Philadelphia-born sci-fi writer, and fellow co-founder of the speculative arts collective we call Metropolarity.

“I used to be all about wanting to live in this sci-fi future where we have augmented bodies,” Téllez explains. Now, they see the language of this utopian dream as problematic.

“To me hacking is like you are subverting a system as an act of anti-authoritarianism,” says Téllez. “To use the word hacking on one’s own body is sort of treating it as a threat … Why would I hack my body? I want to take care of my body. I want to nurture my body. I want to listen to my body.”

While transhumanists and privileged bodyhackers see the body as something to overcome, many Afrofuturists like myself see the value in using one’s body as a technology in the everyday.

Indeed, some interpretations of transhumanism and biohacking seem to have eugenic perspectives. In the quest for the erasure of disability, there is the threat of erasing the generations of knowledge that our bodies contain, especially those of us who have inherited trauma and traditions of resistance — Black people, Indigenous people, people displaced by war and, queer and trans people, disabled and neurovariant folks.

Afrofuturism works to uncover and build new possibilities for Black people. For me and my community, Afrofuturism is not only Black science fiction, scholarship or theory. It encompasses all of the speculative practices and traditions that Black people have used, currently use, and will use to find liberation. It is making a way where there is one. “Code switching is a daily technology,” says housing lawyer and Afrofuturist Rasheedah Phillips. Phillips mentioned being aware of this body hack lately in her video conferences with non-Black colleagues, noticing how Black people have learned to almost automatically project subtle softenings of their Blackness when in white spaces. For us, to code switch is to project an acceptable, safe, body in spaces where White culture dictates access to resources.

Phillips is one half of the Black Quantum Futurist Collective, a Philadelphia-based force that combines art, quantum physics and sound to resist the constant trauma and displacement that Black people face both in their neighborhood in North Philly, and beyond. BQF believes that Black people can collapse time itself to draw upon shared histories and tools of survival, and that they do all the time. Phillips uses the example of the waiting room to demonstrate this time hacking.

“I get a lot of anxiety waiting for doctor’s appointments,” she explains. Given Black womxn’s long gruesome histories with Western medicine, Phillips says she copes with medical visits by intentionally dissociating into a state of future memory. “It’s like, you have already gone through this. You’re in the future. You’re just waiting for your body to catch up.”

Perhaps this is why, especially now, biohackers with life experiences marked more by privilege than brutality don’t always see the value in preserving the wisdom of bodies deemed unruly by society.

Camae Ayewa, artist and musician also known as Moor Mother and second half of BQF, says that despite the limits of a bodyhacking culture centering whiteness, she thinks it’s important to use these terms to assert the legitimacy of Black bodily technologies.

“We’ve always hacked nature and manipulated nature,” says Ayewa. “So there’s a value in reclaiming it and in co-opting the current language because that is what we do.”

BQF combines their Afrofuturistic practice with anti-gentrification and collective memory work in North Philadelphia. In a collection of sci-fi stories Recurrence Plot and Other Tales, Phillips outlines how time experiments can help readers escape linear, Eurocentric conceptions of time to resist oppression.

One such exercise requires the use of mirrors and witnessing to bend time, explaining how the brain, light, and space interact to define and bend reality. In the context of the Black body, her words mirror those of Franz Fanon, who’s Black psychoanalytic theory concerned the absurdity of being witnessed by white people, and the subjectivity of reality based on those witnessings.

Ellen Sebastien Cheng, an Oakland, CA-based theatre artist, works with site-specific performance and rituals as an Afrofuturist technology. Her project House/Full of Black Women, with co-collaborator Amara Tabor Smith, does so in protest of sex trafficking. Cheng says she’s observed how privilege can prevent those bent on body optimization from listening to the wisdom of the oppressed.

“If you are an able bodied white male who has not had to do a lot of exploration or critique about your relationship to the body, then the idea of biohacking and transhumanism is that once you have it all, all of your abilities, all of the normal that you think you’re a part of, then you might as well transcend that normalcy’s limits,” she says. “There’s no disability justice frame put towards it.”

Quantum scenes and liberated futures

I find myself these days constantly revisiting scenes from my career working with young people in shelters and psychiatric institutions. I dreaded those nights when supervisors called emergency services to respond to a youth in crisis. An agitated Black or brown kid would inevitably be met by a set of jumpy police officers. I would immediately morph from being a mental health worker into a hostage mediator, regulating the nervous systems and heart rate of the kid I must protect while using my own body to protect them from the officers exacerbating the situation.

The first time, I made the mistake of touching the police officer who knelt on my suicidal 15-year-old client’s back and threatened to break her wrist while he cuffed her. Suddenly, his hand went to his gun and a flashlight shone in my face. He was screaming about physically touching an officer of the law while the kid called my name, and it all became a nightmare. Assaulting, breaking, maybe killing our bodies for good simply because we reminded him of his own.

Over time, I became practiced, mechanized, a literal “ambulatory arm of capitalism,” as an old social work professor once told us. My skills in youth biofeedback in the face of state violence became stunning, but disturbing. How do we ‘health’ workers oil the wheels of dehumanization?

In the same moment, I am reminded that through centuries of colonization, genocide, and dehumanization, we have always developed tools and techniques and technologies to help our bodies and minds withstand attacks. This is the difference between shortcuts being sold as a “hack” and actual practices of medicine and healing, of learning about our bodies rather than trying to defeat or dispose of them.

For me, Afrofuturist media, theory, and practice provides access to ancestry technologies that have always sustained Black people and the opportunity to create new ones for today’s challenges. I look at the everyday ways Black people shapeshift, control, temper, and use our bodies to get by, how we find joy and humanity, take control of our health all on our own terms.

We have the tools and knowledge to keep biohacking our way through dehumanizing conditions. It doesn’t matter to me if the tech economy, the macho hacker subculture, or the Ivory tower intellectuals want to call this biohacking or not. Like Nanny of the Maroons, our bodies’ adaptations go undetected, confounding the forces that wish to contain them.

My hope is that we can begin to use these ancestral body hacks to do more than just get by. I refuse to continue teaching Black people how to make their bodies cope with the dehumanization of late capitalism and the carceral state. Rather than transcending the fallacies of our bodies, we must collectively undo the unnatural order of anti-Blackness and colonialism in our communities. That is the real disease.

The work continues. Youth still need housing, elders still need their meds, and me and my homies still need to find a way to laugh. So in the meantime, we will be busy building new worlds right here, where being Black and visible is not dangerous, and continue to prime our Black bodies for futures filled with joy and liberation.

*

Ras Cutlass is a Philly-based sci-fi writer, mental health worker, and founder of Deep Space Mind 215, a platform for the creation of community-grown wellness technologies. They are a co-founding member of Metropolarity sci-fi collective alongside Rasheedh Phillips, Alex Smith, and M. Téllez. Their work can be found at cutlasstheory.com and at metropolarity.net

RESOURCES

Bodyhacking:

* Please Try This At Home Conference

* Hackers on Planet Earth conference

* BioCurious and Open Insulin citizen science projects

* The Xenofeminist Manifesto by Laboria Cuboniks

* The Cyborg Manifesto by Donna Haraway

* Body Minds Reimagined by Sami Schalk

* “A Young Thug Confronts His Own Future” by Ras Cutlass

Afrofuturist & sci-fi practice:

* Deep Space Mind 215

* Space-Time Collapse Vol II: Community Futurisms, by Black Quantum Futurism

* Community Futures Lab

* Style of Attack Report, a book by Metropolarity