art by JW Pang

art by JW Pang

By Al Donato

Silvia Moreno-Garcia will destroy us all.

Moreno-Garcia lives in Vancouver, but she’s unleashing her terrifying brood across the world in the upcoming People of Colo(u)r Destroy Horror!, a special issue she’s edited for Lightspeed Magazine. This edition is just one of several offshoots of Lightspeed’s successfully crowdfunded issues devoted to speculative fiction writers of colour. Through initiatives like these, today’s writers who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) are including themselves in a narrative landscape that has long been an ethnic snowstorm.

Speculative fiction does as it suggests. Genres that fall under this mantle, such as fantasy, horror, and science fiction, ask “what if?” with powerful institutions and universally held truths, refusing to accept situations as they are, be it from post-apocalyptic wastelands to oppressive intergalactic dictatorships. Similarly, spec-fic writers of colour resist oppression by virtue of their existence. They’re told book covers with faces like theirs won’t sell; their readership can learn Tolkien’s Elvish, but will balk at patois. The message is clear: give up, this isn’t a craft for people like you. But now more than ever, emerging BIPOC storytellers are striking back and terraforming the literary scene so that it’s habitable for all. Unafraid of reimagining realities for brown bodies and queer love, a new wave of spec-fic writers are building on the work of past generations; in doing so, they’re smashing through the publishing industry’s status quo.

History

From the get-go, Canada’s speculative fiction scene has been racially charged. An “electric Chinaman” jump-started it all in Tsab Ting, the first documented Canadian sci-fi story, written by white female writer Ida Ferguson under the male psuedonym Dyjan Fergus. It was harder to find people of colour behind the bylines; there’s no way of knowing a definitive early history of BIPOC speculative fiction writers, since marginalized writers often find safety in aliases (much as Ferguson did with her male alias.)

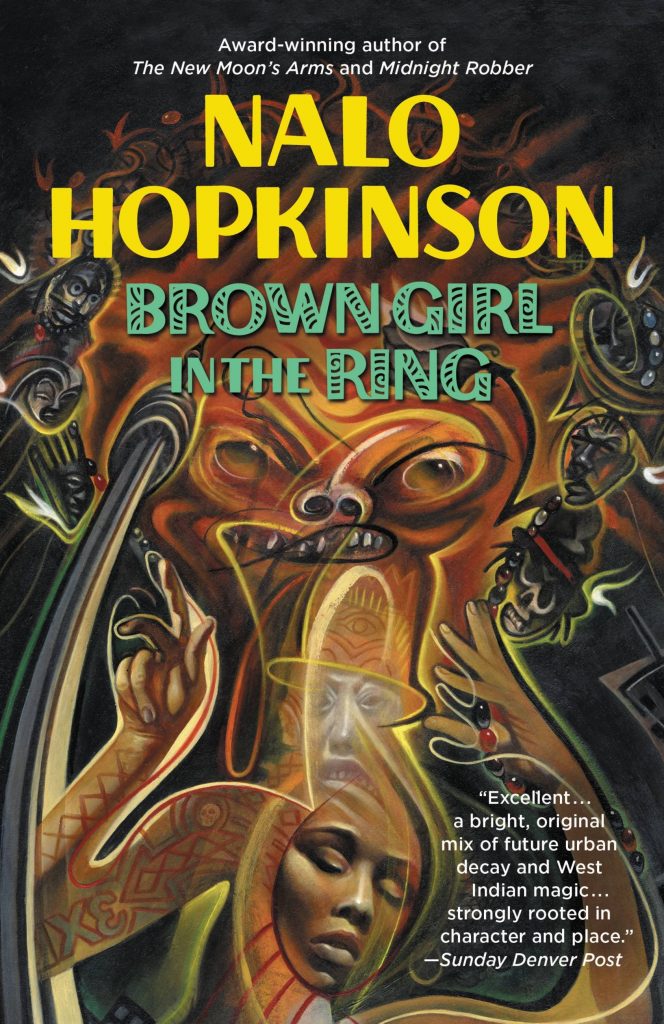

When Nalo Hopkinson first started, she scoured the shelves for Black writers working in science fiction and fantasy. She found five living ones in Samuel R. Delany, Steven Barnes, Tananarive Due, Charles Saunders, and Octavia Butler. Hopkinson and Butler were Clarion writing workshop students while Delany was teaching, each becoming writerly titans in their own right.

When Nalo Hopkinson first started, she scoured the shelves for Black writers working in science fiction and fantasy. She found five living ones in Samuel R. Delany, Steven Barnes, Tananarive Due, Charles Saunders, and Octavia Butler. Hopkinson and Butler were Clarion writing workshop students while Delany was teaching, each becoming writerly titans in their own right.

Delany mentions the duo in an essay detailing racism he encountered from the industry. He describes fighting the urge to roll his eyes after winning a 1967 Nebula Award for Aye, and Gomorrah, when I, Robot author Isaac Asimov jokingly told him: “..we only voted you those awards because you were Negro.”

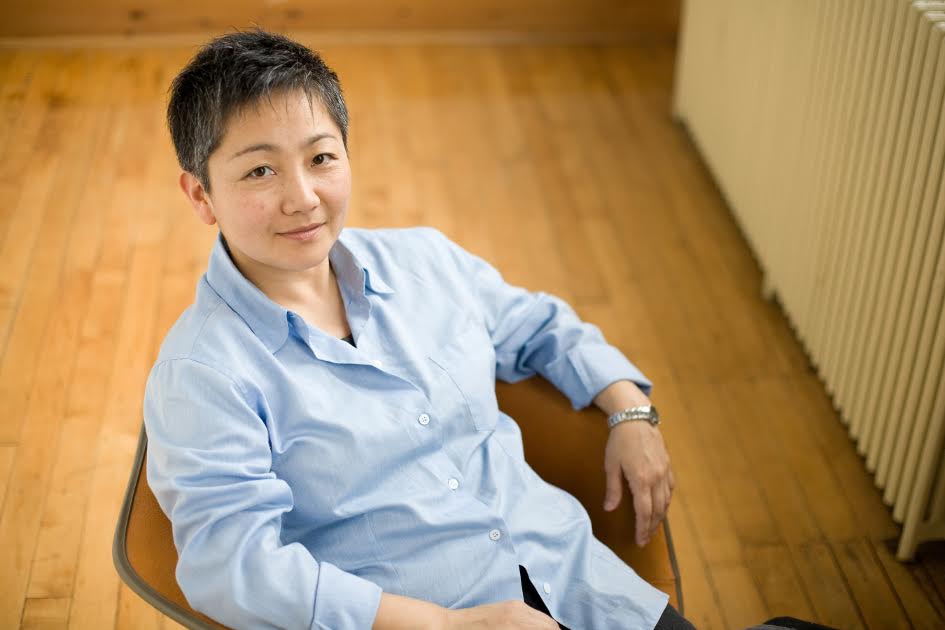

Although untrue for the much established Delany, tokenism is a real fear for many writers of colour. Hiromi Goto, who bears the mantle of Canada’s first Japanese published speculative writer, remembers getting Highlander vibes in her early career.

“I’d say that in the 90’s there was a sense that ‘there could only be one!’” Goto says, referring to the idea that there could be only one successful writer from each culture.

“Professionally published speculative fiction in Canada at that time felt predominantly white. I felt a strong desire to bust that open.”

Beyond themes, heritage for Goto influences her formatting. The Japanese pronoun system is a web of inference, honorifics, gender, and region, reflected in Goto’s liberal use of sentence fragments in her work.

“This is literally how I think and is deeply a part of my writerly voice,” Goto says. “Some people may say: write in the way that most people will understand most easily. I don’t agree with that thinking. Instead of re-inscribing what has been expected — heteronormative white culture — we actually need to write and read from a broader range of voices, aesthetics, knowledges. Many readers are dying to read stories like this.”

Nalo Hopkinson

Nalo Hopkinson

Hopkinson is a testament to that demand.

“I believe it was a revelation to science fiction community when I used some Anglo-Caribbean languages and vernaculars in my writing,” she writes in an email interview, where she later notes that some sci-fi readers found her usage of Caribbean Creole too difficult to understand. “This in a field where some fans will happily learn Klingon,” she adds.

“Science fiction and fantasy are, in many ways, about culture, and about what happens when cultures meet and one has more devastating firepower.”

Who Are Spec Writers Of Colour Now?

In present day and present time, writer, educator and activist Whitney French is creating queer Black women at the end of the world.

A daughter of the African diaspora with Jamaican parents, she savours creators of colour when she can: Maori folk tales by her bedside table, shadism discussions with Chinese friends, and listening to Caribbean field recordings while working on her sci-fi verse novel. Among other things, the novel, whose working title is O, examines cyber technology, queer love as a radical act, and Black and Indigenous solidarity.

French is reverent of those who came before her, writing her into existence. At a Montreal pitstop of her “Writing While Black” French and participants mulled over how to achieve a “Delany feeling of Blackness,” one that went beyond caramel mocha frappuccino skin colour descriptions.

These generational contributions have coaxed a hivemind for Black writers, where they can delve into shared experiences that are informed by schools of thought and storytelling traditions.

“Black imagination to me is what makes me wake up in the morning. In this insidious, racist, capitalistic, colonial, ableist, homophobic [world] … activating the potential for imagination is vital for the liberation of people of colour and Black and Indigenous folks in particular. I cannot stress that enough,” French says. “’Imagination without an ends or product or result can be freeing in a way that leads to actualizing futures. It’s breath. It’s past-present-future in a singular moment. It’s our great-grandchildren, it’s survival, it’s all of that.”

Black imagination has contributed whole new genres to speculative fiction, including Afrofuturism, which ties in themes of Black liberation, feminism, and sci-fi. “Visionary fiction,” a term created by activist Walidah Imarisha, refers to trauma-borne works that visualize futures that overturn existing social inequalities, like police brutality.

Between clacking on her typewriter and perching on Toronto tree branches, French has contributed to both these genres. But she finds publishing opportunities have been rough.

“It’s one of those industries that is stubborn as hell and won’t take risks on new voices. Ontario is interesting because we have Black writers killing it, both in sales and with awards. Still, there is mad resistance to take risks on writers of colour,” French says.

The resistance is backed up by dire numbers. A 2016 report conducted by the short-story magazine Fireside Fiction found that less than two per cent of speculative fiction short stories published in 2015 were written by Black writers. Relying mainly on self-reported data from 63 magazines, the study acknowledges its shortcomings and suggests that the submission rate is higher, possibly around eight per cent.

Moreno-Garcia is proof of the difficulties lying in wait for those who go through the traditional publishing route. As the author of Signal to Noise, a supernatural romance set in Mexico City with 80’s music on heavy rotation, she’s garnered acclaim. But too often she finds herself being pigeon-holed. The fact that her book is more often forgotten in recommendations for music-themed books, but is always pinned to diversity-related lists.

“I don’t mind being called [a person of colour], but I mind when that’s the only thing about me,” Moreno-Garcia says.

Breaking even for the Mexican writer is a struggle she’s dealt with for anthologies and unknown small presses.

“When you’re writing speculative fiction, and you’re in Canada, it’s like a no man’s land. You can’t turn to the government for funding and there’s virtually no commercial companies,” she says. “The people who fund grants … they want to fund the ‘real’ Canadian experience.”

Something like that even happens to writers whose home and native land is right here.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been met with disappointment when my stories aren’t ‘Indian’ enough, whatever that is,” says Métis & Ojibway writer Cherie Dimaline.

In spite of barriers, speculative writers of colour are reaching higher profiles. This is thanks to older writers setting precedent. Delaney, Goto and Hopkinson are queer pioneers in speculative fiction, featuring diverse gender expression and sexuality in their works long before diversity was a buzzword. The Carl Brandon Society was created in response to Delany’s scathing essay almost 20 years ago, and continues to award scholarships to writers of colour.

The web is a conduit for allyship. Readers searching online for writers of colour could gush about their favourites openly, while taking to task systems that don’t prioritize their interests. We Need Diverse Books, which started as a hashtag and is now a fully-fledged organization, provides opportunities and grants for writers from various backgrounds.

But not everyone is happy about the new faces. The success of marginalized authors on both bestseller lists and awards ceremonies has ignited a civil war between speculative writers.

In 2014 John Chu’s short sci-fi story about a closeted Chinese man won the Hugo Award. The win inflamed the notorious Sad Puppies voting bloc, a Gamergate-affiliated campaign led by a cluster of conservative science fiction and fantasy writers. They were similarly enraged by other wins by diverse writers, believing that storytelling should take place over progressive themes. Since then, they’ve made it their mission to vote those stories out of the Hugos; one that’s been thwarted and ridiculed by supporters of diverse writers. In past years, voters chose no award over anyone on the Sad Puppy-recommended ballot.

What’s Next

Cherie Dimaline

Cherie Dimaline

Moreno-Garcia, French, and other working writers are already comfortable in their own skin, partially by choosing to work with publishing houses that work to centralize their identities. Cherie Dimaline has written for two Indigenous publishing houses in the past, and specifically commends Cormorant Books for learning how to properly edit Indigenous work.

As a kid, Dimaline moved around a lot. The constant upheaval made her draw comfort in her grandmother’s lively stories. When she encountered speculative fiction, she was reminded of her family’s folklore.

“I have a pretty Indigenous approach to story, which is to say that not everything is as it seems and sometimes if you go walking in the woods, the woods will walk with you,” she says. She cites a seven-generations method that Indigenous storytellers adhere to: representing a culture that honours ancestors from seven generations ago, with the foresight for what impact will occur for those seven generations ahead.

“This is where a lot of the importance of Indigenous work lays, in that worldview that is different and careful,” she says. “It is also imperative that we write ourselves into existence. People are still shocked that we are here in the present, never mind in a future or in space.”

She’s doing her part for generations ahead, by getting involved with a Humber College program that teaches editors how to work with Indigenous text.

Hiromi Goto

Hiromi Goto

With more BIPOC writers at the helm, speculative fiction’s future is promising. Without writers of colour, empty Eurocentrism makes up the literary world’s darkest timeline – one where the imaginative borders of speculative fiction don’t extend to the Albertan prairies, home to Goto’s roaming genderless frog demons from The Kappa Child. Toronto is likewise barren of Hopkinson’s young seer mother from Brown Girl in the Ring, capable of summoning ancestral spirits.

While difficulties remain for speculative writers, it can’t be denied that their work is valued. Consistently, writers of colour attribute each other for inspiration and heap love on understanding editors more often than they chew out bad ones.

Hopkinson has a word of advice for new speculative writers of colour too discouraged to think they stand a chance: don’t stop.

“Do not assume that. Do not do the work of the assholes for them. When you encounter obstacles, go to the next door,” she says. “The assholes do not absolutely own this genre. You may be surprised at how many allies you find.”

Al Donato gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ontario Art Council’s Writer’s Reserve Program.