by Rupi Kaur (2015)

by Rayna Livingstone Lang

In 2015, Toronto-based artist and poet Rupi Kaur posted an Instagram photo of a fully-clothed woman in bed with a menstrual stain on her pants and sheets. Kaur’s work was dubbed as offensive and the photo was pulled by Instagram for not following community guidelines, which prohibit sexual acts, nudity, and violence — none of which are present in the photo.

Instagram did eventually restore the image after significant backlash and claimed the censorship was “an accident.” A number of commenters labeled the scene as “gross” and “unpure”, with one user going going so far to say “being a woman is honestly disgusting… I would do anything to kms (kill myself).”

So why is menstruation still being treated as something “unpure?” How is this fact of life for women so cloaked in taboo that it is as unfit to view as the Ark of the Covenant? Kaur’s virtual knuckle-rapping confirms an ages-old practice of women being told that their periods are dirty, make them crazy, and should be kept discreet for comfort of others. A growing new art movement aims to confront and eliminate these mentalities, elevating the act of having one’s period in ways that are joyful, angry, political and defiant.

Menstrual art is exactly what it sounds like it is: art focused on the so-called “crimson wave,” with many works being created using actual menstrual blood. Artists who dabble in this bloody and provocative medium create pieces that address societal negativity and body shame, and sometimes take more political stances against rape and other forms of violence against women. “[Menstruation] is like a symbol of power that has been shamed by a dominant culture,” says Toronto- based artist Jess Dobkin, known for performance pieces incorporating her body. “It gets stigmatized because of the tremendous power of women, and not just women, but the power of the body… and these stigmas were not put in place by the people it’s impacting and it has become internalized.”

When the word “period” or any of its related euphemisms are uttered out loud, they’re usually met with with cringing and shame. Even tampon and pad advertisements always use words such as “discreet” and “invisible” to describe their products. In popular culture, periods are often treated as an embarrassing scourge — see the horrifying opening shower scene of Brian De Palma’s horror film Carrie and King of the Hill’s episode “Aisle A8” in which squeamish Hank Hill has to help his young neighbour with her first period — or an almost painfully precious gift of “womanhood” smothered in cutesy phrasing and squeaky-clean resolutions (see Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret and the episode “Busy’s Curse” from the Canadian TV show Ready or Not). In the introduction to her book Periods in Pop Culture: Menstruation in Film and Television, Australian researcher Dr. Lauren Rosewarne says that these depictions of menstruation help to “reinforce popular ideas related to taboo, stigma, and secrecy.” As a result, menstrual art is regularly dismissed as attention- seeking gore rather than a statement.

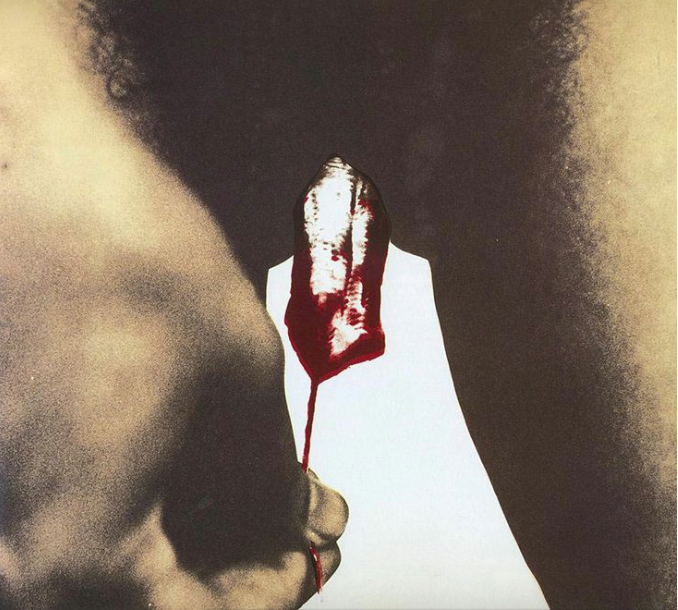

Red Flag by Judy Chicago (1971)

Red Flag by Judy Chicago (1971)

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when menstrual art began, but its roots lie in the feminist art movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. American artist Judy Chicago is often credited as being one of the first to recognize the artistic merits of the crimson wave, with The Curse crediting her work to “freeing women artists from the menstrual taboo.” Chicago exhibited a handmade lithograph, Red Flag (1971), which featured the artist removing a tampon from her vagina. Many people mistook the tampon as being a bloody penis, which Chicago stated was “a testament to the damage done to our perceptual powers in the absence of female reality.” As part of the collaborative installation and performance space, Womanhouse (1972), Chicago created the controversial Menstruation Bathroom, a white bathroom with used and unused menstrual products. The centrepiece was a trashcan overflowing with used tampons, reminding us that hiding our used “cotton pony” is a futile and unnecessary effort.

Jess Dobkin’s Bleeding at the Ball (2011)

Jess Dobkin’s Bleeding at the Ball (2011)

Chicago’s work helped to establish the practice of menstrual art and many artists followed up with their own bloody masterpieces. In 2011, Jess Dobkin attended the annual Powerball fundraising gala, populated by elite patrons of the Toronto art world, in a fancy white dress with an unmistakeable red stain on the back. Photographer Henry Chan documented the performance which was aptly called Bleeding at the Ball. “People wouldn’t even name it. They’d say ‘you had an accident’ or ‘there’s something on your dress’,” Dobkin said about the experience. “Some people pointed it out to each other… there was even a woman in the bathroom taking a picture of it.”

Vancouver photographer Jackie Dives created a series of menstrual portraits of women on their periods titled Menstruation (2015). In addition to her portraits, Dives also filmed a short documentary, Period Piece (2015), in which women discussed their first experiences with the ruby tides and also weaved a series of menstrual themed wall hangings. Artists like Dives and Dobkin bring menstruation to the forefront and playfully negate the ways menstruation is considered a social faux pas or a secret. Other artists have chosen to use menstruation as a metaphor for ways in which women are socially, culturally and sexually subjugated.

Since 2006, South African artist and activist Zanele Muholi has been collecting her menstrual blood and making mandalas. The series, called Isilumo Siyaluma (the Zulu phrase for period pain), is a response to curative rape, which is a disturbingly rampant hate crime against the LBGTQI community where a person is raped to “correct” their sexuality. Each pattern is made to represent a victim or survivor of this loathsome crime. In a video interview with Toxic Lesbian, Muholi explains the project’s symbolism: “The same passage in which we bleed — which is a sacred space for us female bodied beings — is the very same space that is being violated. And it’s that very same space in which we are born.”

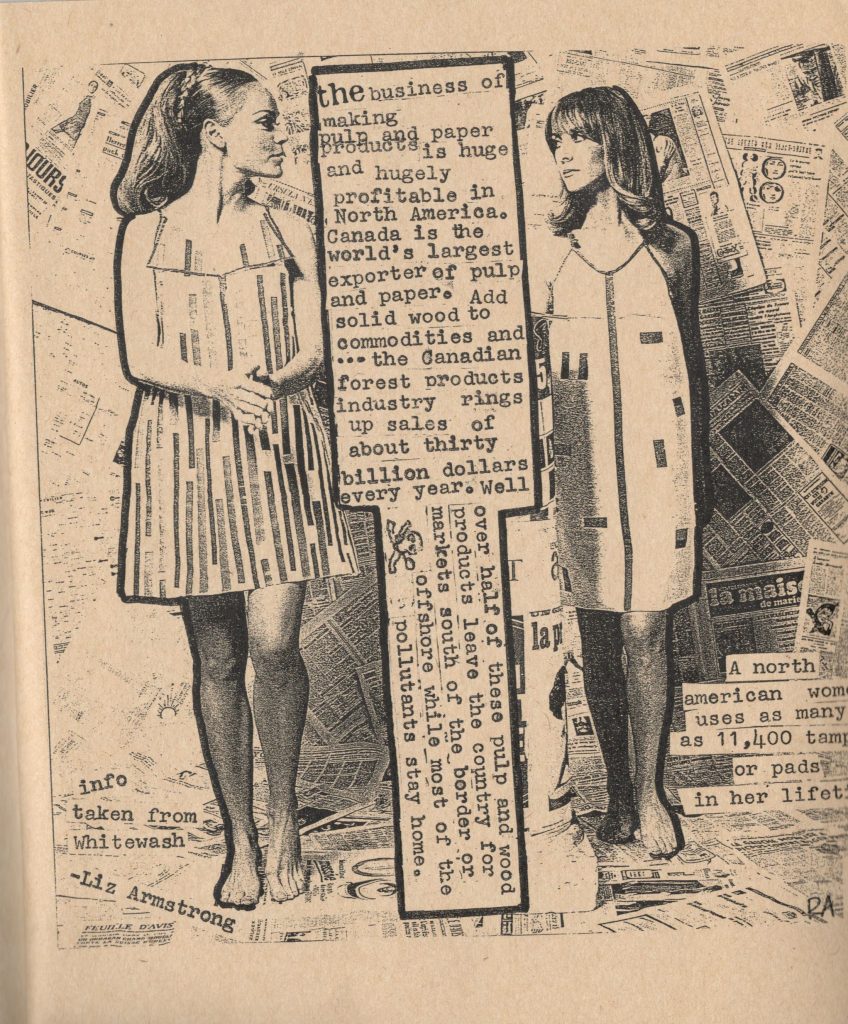

from Red Alert zine by The Blood Sisters (2011)

Menstrual rights are not universal, with only 12 percent of women and girls having access to sanitary products. Menstrual education, as a whole, is also lacking with many women not having an understanding of their own cycles. In response, loads of zines have been created to help educate women on their flow. Zines like the Red Alert series by the Blood Sisters, a former Montreal- based organization dedicated to feminine hygiene, detail the political and societal issues of menstruation as well as outlining the risks of mainstream products, such as Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS). They offer natural alternatives, home remedies for cramps and late periods, provide instructions for making reusable pads, and include art and poems in their zines.

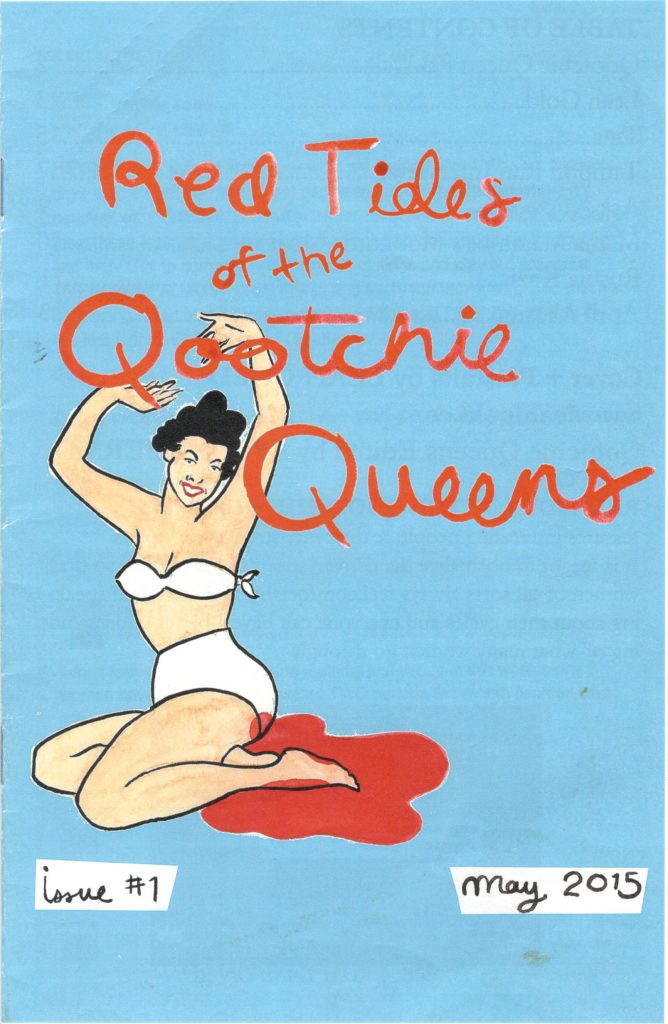

Issue 1 of April Aliermo’s Red Tides of the Qootchie Queens (2015)

Issue 1 of April Aliermo’s Red Tides of the Qootchie Queens (2015)

Feminist Compilation series 1234V put together their own bleeder issue in 2008, with stories from both men and women. Meanwhile, April Aliermo’s 2015 zine

offers anecdotes in addition to advice and an interview with the creators of a menstrual themed video game. These publications act as women’s health pamphlets, and their stories especially help to normalize experiences and alleviate shame.

Menstrual art works to depict the beauty of the cycle and uses it as an argument towards ending negativity. It’s seen as exceptionally radical, but it shouldn’t be: bleeding is something a woman’s body does and it should be treating with the same normality we grant to every bodily function. It’s not gross, it’s not shameful, and it’s not a secret. Accept that reality and let respect flow.