ARE YOUR MESSAGES SECURE?

You might have used encrypted communication apps like Signal, and these handy tools have become ever more popular, and more critical, as threats to our privacy from government and corporate actors continue to intensify. These technologies have come a long way. But would you guess that the only encryption method on earth that can be completely uncrackable isn’t electronic at all? In fact, it’s a tool that is more than a century old, and technically, you can do it with just a paper and pencil. Meet the one-time pad (OTP).

Just like the stack of sticky notes or the tear-away calendar on your desk, one-time pads are a lot like they sound: a stack of paper sheets, each containing a single-use key used to encode a message. First described by cryptographer Frank Miller in 1882, this method requires coordinating ahead of time with your recipient to exchange the key to your code, and to agree on rules. It might take some effort, but this analog encryption technique can yield interesting applications for those working in intentionally temporary media.

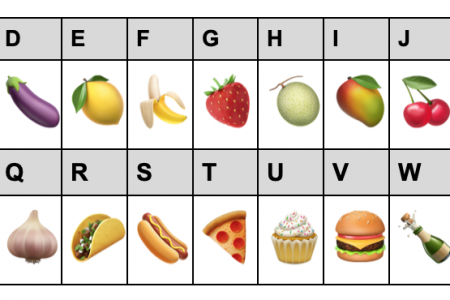

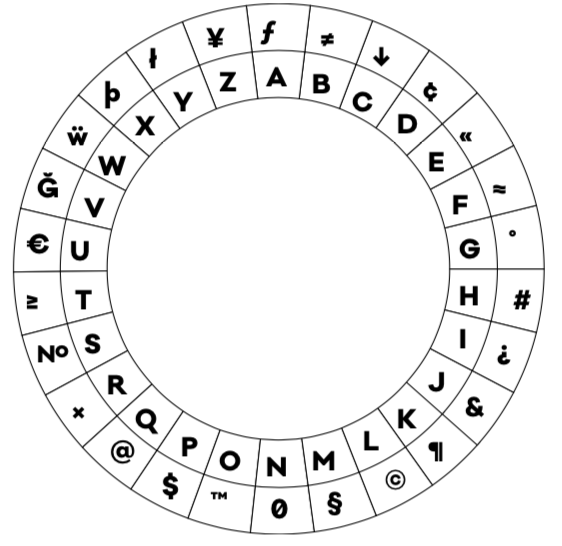

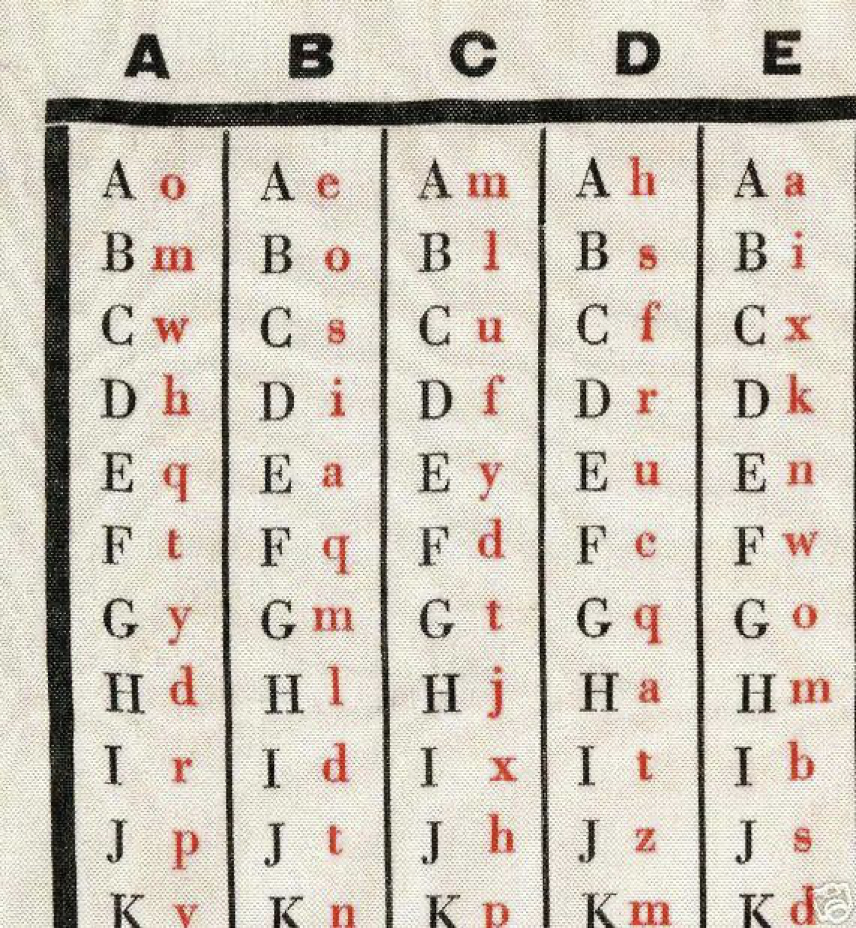

The one-time pad method has been a favourite of spies and governments for decades because of its durability, consistently defying the most clever computers then and now. During World War II, British intelligence agents would use code charts like the one above, printed on silk rather than paper, since it was quiet (unlike crinkly paper) and could be tucked in a jacket or used to tie hair. They often would use pinpricks or embroidery to denote which one-time keys on the table had already been used up.

But before you start marking up your old scarves with sharpies, we’ll have to understand how one-time pads work, and ciphers more generally. Let’s start by considering one of essential kinds of these keys, the substitution cipher. Substitution is what it sounds like — each letter has an equivalent form in the key. In the example below, we see how this substitution cipher substitutes a different number for each letter of the alphabet. So, encoded text using this cipher for “hello” would be 8-5-12-12-15. But we’re not limited to numbers, we could also use emojis or even other letters and alphabetic symbols.

Today, we have access to websites where you can paste in encrypted text to help decode simple substitution ciphers. These decoders identify the letters/numbers/ emojis that appear most often in the encrypted message, and thus might correspond to the most commonly used letters in the original language. So while substitution ciphers can make a fun puzzle for a zine, it’s not something you’d really want to use for very sensitive or important information. Many of these ciphers were easy to crack using simple math and a bit of time and effort.

To counter this, Miller removed the consistency factor, inventing a method where each letter in the entire message gets a unique, random substitution assigned to it. The first letter in a message now has 26 possibilities of what it could stand for. And the letter next to it could also have 26 entirely different possibilities of what it could stand for. And as the number of letters in your message increases, the combinatorial possibilities go up astronomically, too high even for the most advanced computers in our world to guess in our lifetime.

YOU CAN DECODE AN OTP MESSAGE RIGHT NOW!

So let’s imagine that I’m your partner in zine crimes, and I’ve given you three very exclusive, members-only issues. You’ve been briefed that you’ll have to keep both the message and the cipher a secret and not reuse them anywhere.

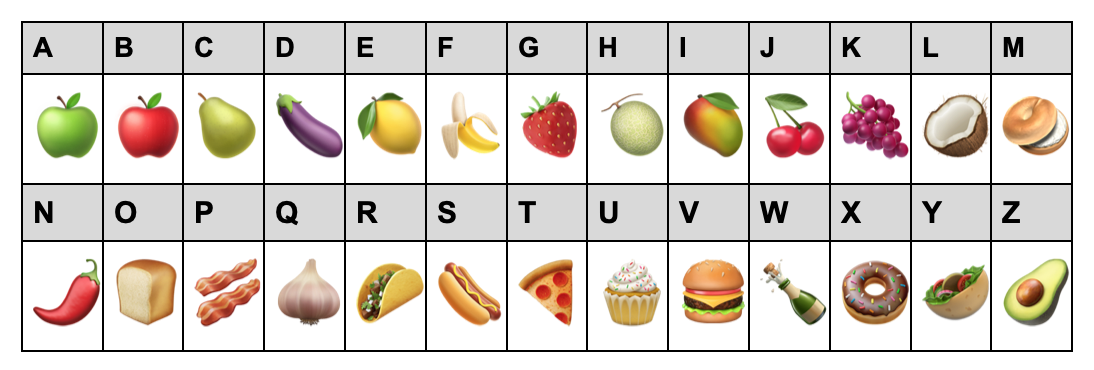

The first zine has the smaller version of a one-time pad chart, like below. I’ve used this chart to encipher my message. Each column is used only once, ever, to indicate the key for a single letter.

This chart can be used to unlock the second zine, which contains my ciphertext. Once you crack it, the zine text will tell you about a special gift I’m giving only to my elite crew of zine subversives. In this case, the ciphertext is four letters: “fody”

Lucky for you, I also give you secret zine three. Zine three includes the key to this message, which directs us to use the chart to interpret each individual letter of the above. In this case, the OTP Key is “DAEC”.

So, you have the code chart zine, the ciphertext zine issue, and the key issue, Now, you can finally decode! Each letter takes three steps:

Find this column letter:

|

D |

A |

E |

C |

Find this red letter in that column:

|

f |

o |

d |

y |

Write the corresponding uppercase letter:

|

|

|

|

|

Congratulations, you’ve just deciphered a one-time pad message by hand! You truly can have your cake and eat it too. You can encipher a message the same way, by doing this process backwards with your code chart I gave you in your first special members-only issue.

However, if you were really using your silk code chart, you’d now want to mark out columns D A E and C to not use those columns again. As you can imagine, this means that charts get used up fairly quickly, like having to bake a new entire cake after you’ve cut and eaten just a few slices.

Today we’re pretty lucky to have the ability to generate new charts with the help of a computer. Otherwise, we might all just have to sit around singing the ABCs all weekend with graph paper and a pair of dice (simpler times). However, if you have all of those, you can Google “create one-time pad with dice” to read some methods to create and exchange your own code books with friends. You’ll get the hang of it quick.

Assigning every letter in a message a different random substitution letter to make our key is one of the very strict rules of one-time pads. All 4 rules are:

- The key must be truly random

- The key must have at least as many letters or symbols as the original text

- The key must never be reused (not even a part of it)

- The key must be kept completely secret

These rules of use for one-time pad keys must be ironclad in order to be effective, because each additional rule exponentializes the number of possible combinations. With so many possibilities, even our best current supercomputers can’t crack it. There are plenty of variations to bulletproof the cipher, too. Poke around online for examples.

Other sites like boxentriq.com/code-breaking/one-time-pad,will randomize your message as long as you provide a key of your choosing. It can be something that looks rather benign. Try punching these into boxentriq.com

Ciphertext: IVZVSJDVYF Key: BROKENPENCIL

Enciphered messages can easily lurk in plain sight.

TIME AND PLACE FOR ONE-TIME PADS

How practical is the use of one-time pads? During the Cold War, the NSA (National Security Agency) expended astronomical resources to produce 1,660,000 rolls of “one-time tape” each with 100,000 random characters agents could use to create keys of considerable length. This took a huge effort, but worked.

Given that the message key and code books must both be exchanged in secret, it seems like a lot of rigmarole, especially by today’s standards. If you have a secure transmission method for the key, why not use that for the whole message? Modern privacy technologies probably have us covered for many day-to-day uses.

But don’t write off hand-encryption methods like OTP. Should we find ourselves in situations where internet connectivity and even standard messaging like SMS fail us, familiarity with these kinds of multi-component messages can be useful, and above all, it’s the logic behind OTPs that makes them so durable. There are two main rules — only use once, and never share the key. These factors exemplify a kind of time and space-based thinking that we can apply to encryption within ground-level organizing. Let’s ask ourselves, can we separate and distribute different components needed to restrict access to a message, location, or person? Can we establish code and security protocol amongst collaborators ahead of time? Can I provide my fellow organizers with a stack of pre-approved codes, locations, names, or other information only intended to be used once?

The arts provide some special opportunities as well. Imagine splitting across zines so people have to get them all, or sending a key or codebook to select trusted zine rebels? You could even split passwords between two parties who aren’t in contact digitally, so that they would have to meet in person to combine a ciphertext and key to get the resulting plaintext? Overall, careful planning around the when and where of IRL encryption can create an even tighter security culture amongst activists and allies.

Even without ciphers, thinking of time and space as ingredients can be fruitful for creators. What if your project messaged people from a burner signal number? Or perhaps offer IP addresses where a website with your work appears only for a week. Whatever you need to keep inside the group, you’ll enhance privacy more effectively by envisioning how mutual agreement, ephemerality, and consent fit in.

You may not see any use for this “encryption by the slice” right now, but even so, never forget what you have now — the world’s most uncrackable code. You never know when you’ll need it.