The Prophecy

Excerpted from The Lily Pad and the Spider, written by Claire Legendre, translated by David Homel

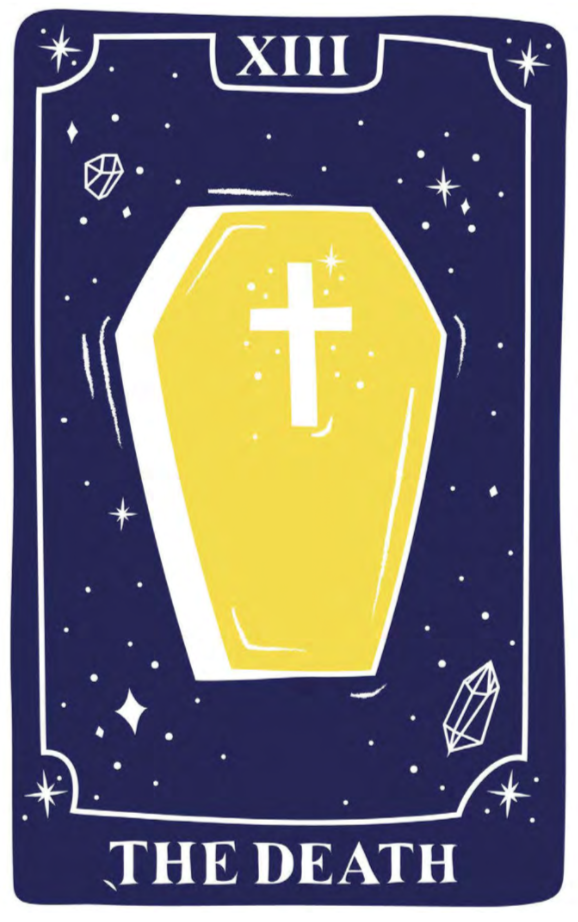

It was supposed to end July 3, 2007. That had been decided long before. More than once, and meticulously so. The idea came from childhood. From school. When I was nine or ten. I had a friend, I forget her name, a little gypsy girl who came in the middle of the year, she was very nice, and could read palms. I liked that because my grandmother read our Tarot when she wasn’t interceding on our behalf at church, she prayed novenas, kept a candle lit for nine days, almost burning down the apartment, consulted a fortune-teller when necessary, and took me to Sunday mass the other times, once a year we went to see Saint Anthony in Padua and brought back large plastic containers full of water from Lourdes that we drank to protect our health and make our prayers come true, our wishes, our desires, all synonyms for the same thing. That was my grandmother’s way of loving us, with all her benevolence she communicated on our behalf with the forces that make decisions: gods, saints, planets, cards, pendulums, black cats, and hats absent-mindedly and unfortunately left on beds, mirrors tragically broken, and worse, the very worst, the neighbour lady who had the nerve to greet us in the morning with a “Good day!” that would bring bad luck, we had to do everything possible to avoid her completely, or as much as we could. One day my grandmother asked her to stop wishing us a good day, and I would have given anything to see the neighbour’s face then or, better still, a few weeks later, when the words crossed her lips again. Good day excuse me.

The little gypsy girl read palms and I don’t know what romantic little game, ill-conceived or perverse, led her to announce one day, in the playground, that I would die at age twenty-seven. I was not overly concerned. Twenty-seven is a world away when you are nine or ten. Early death was a way of escaping old age, no one would see me with faded beauty behind my lace, it was almost flattering with its rock star feel, she added me to the list of the twenty-seven club with Jim Morrison, Hendrix, Janis Joplin, long before Cobain and Winehouse joined. I was ready for that.

There was nothing tragic about the prediction, and I didn’t mention it to my mother. Even then I understood that at age twenty-seven, a person doesn’t die of a disease. I knew I would escape death by overdose because, after the presentation the volunteer from the prevention centre gave us at school, drugs weren’t my thing. At twenty-seven, a person dies in an accident. The idea, both nebulous and very clear, took hold in me: I would die in a car wreck at that fateful age.

I never got my driver’s license.

When I was thirteen, the Oliver Stone film launched a very convincing Doors revival. I spent my weekends in smoky bars, smoking and listening to blues bands playing ecstatic and melancholy tunes (sometimes one, sometimes the other, sometimes both). That was when we fomented our project, Lisa and I. Lisa was my best friend. Same blond hair, same green eyes, but much more petite and cute and pretty than I was, which accentuated my awkwardness, my skin that refused to glow, my thighs that kept expanding. Her skin, as she grew older, would stay smooth, and when she opened her thighs they would be svelte. The boys used to ask me if I was chaperoning my little sister, and that was my only revenge since it drove Lisa crazy.

To tell the truth, that wasn’t my only revenge. Lisa was probably more lost than I was. She slept at my house whenever she could. She would steal one of my barrettes, a tube of lipstick, a pen. She had lost an older sister when she was a child, a sweet blond-haired girl dead of meningitis at age nine. She took it out on me. As an only child, I loved exclusivity, one-on-ones, secrets, endless conversations, shared dreams, but at a certain point during the weekend I needed to be alone and very gently, I showed Lisa the door (if that can be done gently).

Lisa and I whiled away endless afternoons crisscrossing the city and dreaming of love that would necessarily be wearing a bad boy look, a musician if possible, since we had seen The Doors and wanted to suffer the way Pamela Courson had as long as our Jim was as exciting as the original model, with a beautiful deep voice, and long hair if it was up to us, and many attractive and untamable deviant characteristics. Our favourite line — “you actually put your dick in that woman, Jim?” — seemed to speak of a life of adventure. I watched My Own Private Idaho and dreamed of being a miserable young homosexual ephebe. Live fast, die young: I built my dream on that.

I remember a day spent methodically tearing down Front National posters in front of my school. As we broke our nails pulling off the corners of photos of Le Pen and Mégret already adorned with graffiti mustaches, we considered our future. It was the pre-grunge era, we listened non-stop to Use Your Illusion without suspecting how much harm the song would do us later on (not to mention our shame at having liked the record). Lisa pictured herself flirting with Axl Rose and I saw myself with Slash in a red convertible in the Arizona desert, stopping along the road to fuck, passionately destroying our bronchial tubes and various motel rooms. The images were very clear. I remember perfectly. We just needed a way to contact them. I wrote stories but that wasn’t enough, Lisa wanted to be an actress, which seemed childish. We smoked rose petals and a lot of cigarettes. Lisa puffed on a joint if the boys had one. I cleaned up her vomit. I never got drunk. We drank Malibu and milk cocktails. We decided to die at age twenty-seven, I wasn’t sure who started it, probably me because it had been on my mind for a while. We wanted to die on July 3 like Jim Morrison. At first I chose the end of January because I was in love with O. who was born then, but for Lisa, the date made no sense, I hadn’t even introduced her to O. because I was afraid she’d help herself to him the way she did with my barrettes, lipstick, and pens, she’d appropriate him to be a little more me. I began to distrust her. We saw Single White Female together and I kept her at a certain distance. In any case, I dropped the date of O.’s birthday, though he was a singer with a deep voice and magnetic hips, for the more universal historicity of the dead icon. Morrison would be our guide.

On July 3, 2007, we would go to Castellane, a pretty village where my father once took me for vacation (it was known — though there was no relationship — as a place where a cult of crackpots had built spectacular monuments to the glory of their guru). We would spend the night in a grade-B hotel with two gigolos or waiters or tourists, we would treat ourselves to an enormous banquet and an all-time sex orgy, we would try every possible drug and at dawn, a twelve-kilometre ride in a red convertible à la Thelma and Louise to the cliff at Point Sublime, in a white dress and fishnet stockings and a wrist band, completely Courtney Love, a leap into the unknown, bodies shattered on the rocks. Cut!

On July 3, 2007, we would go to Castellane, a pretty village where my father once took me for vacation (it was known — though there was no relationship — as a place where a cult of crackpots had built spectacular monuments to the glory of their guru). We would spend the night in a grade-B hotel with two gigolos or waiters or tourists, we would treat ourselves to an enormous banquet and an all-time sex orgy, we would try every possible drug and at dawn, a twelve-kilometre ride in a red convertible à la Thelma and Louise to the cliff at Point Sublime, in a white dress and fishnet stockings and a wrist band, completely Courtney Love, a leap into the unknown, bodies shattered on the rocks. Cut!

I took photos, scouted the locations, tried out the hotel, calculated the height of the cliff. Thirteen or fourteen short years, and we would add our lives to the pantheon of the Unforgettable. Life to the fullest. Write. Live. Love. Fast, faster. Smoke cigarettes and fuck. Nothing to lose.

Lisa and I stopped being friends when we were fifteen. I tried to survive O. getting married, and she moved to another city to study theatre and live out her dream. The idea of a young life snuffed out too soon remained deeply embedded in my mind, with greater or lesser elasticity and romanticism. At seventeen I said I would kill myself at thirty-five if I hadn’t published anything. My first novel saw the light of day when I was eighteen. It was not unforgettable enough to save me from oblivion. I kept trying to find a way to die in peace. I lived — but not enough — and wrote — not enough. Then, one day, I hit twenty-seven.